THE PURDUE BLOAT STUDY

BLOAT NOTEs:

News From the Canine Gastric Dilatation-Volvulus Research Program

School of Veterinary Medicine

Purdue University

Progress in Prospective Study of Risk Factors for Bloat

Follow-up of dogs in Purdue's prospective study of bloat risk factors is progressing on schedule. By the end of the enrollment phase (March 1997), 1,989 dogs had been enrolled at shows. As described in the last issue of BLOAT NOTEs (Jan. 1997), the study is designed to estimate the incidence of bloat in each of the participating breeds and to evaluate the relationship between bloat risk and body conformation, family history of bloat, diet, and personality factors.

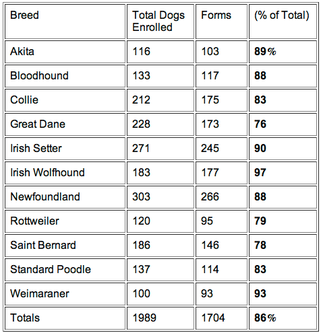

The first step of the follow-up phase was for the owners to complete a Current Status and History Questionnaire for each of their dogs enrolled in the study. Table 1 shows that completed forms were received for 86% of the 1,989 dogs.

Follow-up of dogs in Purdue's prospective study of bloat risk factors is progressing on schedule. By the end of the enrollment phase (March 1997), 1,989 dogs had been enrolled at shows. As described in the last issue of BLOAT NOTEs (Jan. 1997), the study is designed to estimate the incidence of bloat in each of the participating breeds and to evaluate the relationship between bloat risk and body conformation, family history of bloat, diet, and personality factors.

The first step of the follow-up phase was for the owners to complete a Current Status and History Questionnaire for each of their dogs enrolled in the study. Table 1 shows that completed forms were received for 86% of the 1,989 dogs.

Table 1. Response Rates: % of Dogs for Whom Completed Baseline Questionnaires Were Received

Table 1. Response Rates: % of Dogs for Whom Completed Baseline Questionnaires Were Received

This is a very good response for any epidemiologic study, and the response rates of ³ 90% for some breed clubs (Irish Setter, Irish Wolfhound, and Weimaraner) are extraordinary! In addition, some owners who did not complete the baseline questionnaires did return a postcard or phoned regarding 100 dogs, reporting whether or not the dog had bloated and whether or not the dog was still alive. Even this minimal information will allow us to learn about the relationship between body conformation and bloat risk.

Most owners who completed a baseline questionnaire also returned a follow-up postcard in the summer or fall, to report their dogs' bloat status and vital status. Another follow-up postcard campaign will be conducted in January, and follow-up will continue through February 1998. The success of the study still depends on owners' continuing cooperation.

Preparations for data analysis will begin in January. This effort will be strengthened by consultations with a veterinary nutritionist, Dr. Mark Tetrick, The Iams Company, who will advise on how to evaluate the large amount of dietary information provided by owners. Preliminary results of the data analysis should be available by next summer. A final report will be sent to each of the participating breed clubs, the Morris Animal Foundation, and the American Kennel Club Canine Health Foundation.

An Epidemic of Bloat in the US Confirmed -- But Why?

The last BLOAT NOTEs issue reported that the overall frequency of bloat (gastric dilatation with or without volvulus) in dogs admitted to veterinary teaching hospitals in the US increased dramatically (~1500%) between 1964 and 1994, from 0.036% to 0.57% of all dogs admitted. This observation was based on data in the Veterinary Medical Data Base (VMDB), a computerized multihospital record system.

One theory is that this increase is due to changes in breed popularity over the years, i.e., it could be explained if more and more of the dogs seen at the veterinary teaching hospitals were from large and giant breeds at high risk of bloat. If that were the case, the bloat prevalence rates for specific breedsshould be relatively flat.

Another theory is that some widespread environmental change, such as a change in dog food manufacturing procedures, affected bloat incidence. If this were true, the rates for specific breeds would be expected to increase in parallel with the overall rate for all dogs.

The VMDB records were re-analyzed to clarify this issue. First, the diagnostic criteria were limited to dogs with gastric torsion (another term for gastric volvulus). This diagnosis was based on radiographic and/or surgical evidence. Other diagnostic codes, such as dilated stomach, were excluded. Second, the analysis was limited to the years 1975-1996.

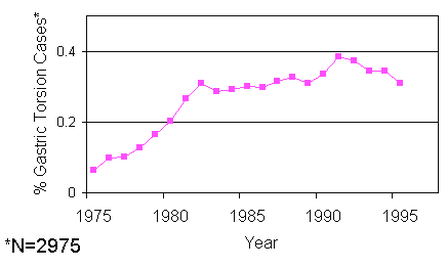

The hospital prevalence curve for 2,975 dogs with gastric torsion (Figure 1) followed the same pattern as the earlier graph: there was a marked increase through the late 1970s, and the upward trend continued, although more gradually. Overall, the frequency of gastric torsion rose from 0.06% of dogs admitted in 1975 to 0.31% of those admitted in 1995, an increase of more than 500%.

Most owners who completed a baseline questionnaire also returned a follow-up postcard in the summer or fall, to report their dogs' bloat status and vital status. Another follow-up postcard campaign will be conducted in January, and follow-up will continue through February 1998. The success of the study still depends on owners' continuing cooperation.

Preparations for data analysis will begin in January. This effort will be strengthened by consultations with a veterinary nutritionist, Dr. Mark Tetrick, The Iams Company, who will advise on how to evaluate the large amount of dietary information provided by owners. Preliminary results of the data analysis should be available by next summer. A final report will be sent to each of the participating breed clubs, the Morris Animal Foundation, and the American Kennel Club Canine Health Foundation.

An Epidemic of Bloat in the US Confirmed -- But Why?

The last BLOAT NOTEs issue reported that the overall frequency of bloat (gastric dilatation with or without volvulus) in dogs admitted to veterinary teaching hospitals in the US increased dramatically (~1500%) between 1964 and 1994, from 0.036% to 0.57% of all dogs admitted. This observation was based on data in the Veterinary Medical Data Base (VMDB), a computerized multihospital record system.

One theory is that this increase is due to changes in breed popularity over the years, i.e., it could be explained if more and more of the dogs seen at the veterinary teaching hospitals were from large and giant breeds at high risk of bloat. If that were the case, the bloat prevalence rates for specific breedsshould be relatively flat.

Another theory is that some widespread environmental change, such as a change in dog food manufacturing procedures, affected bloat incidence. If this were true, the rates for specific breeds would be expected to increase in parallel with the overall rate for all dogs.

The VMDB records were re-analyzed to clarify this issue. First, the diagnostic criteria were limited to dogs with gastric torsion (another term for gastric volvulus). This diagnosis was based on radiographic and/or surgical evidence. Other diagnostic codes, such as dilated stomach, were excluded. Second, the analysis was limited to the years 1975-1996.

The hospital prevalence curve for 2,975 dogs with gastric torsion (Figure 1) followed the same pattern as the earlier graph: there was a marked increase through the late 1970s, and the upward trend continued, although more gradually. Overall, the frequency of gastric torsion rose from 0.06% of dogs admitted in 1975 to 0.31% of those admitted in 1995, an increase of more than 500%.

Figure 1. Hospital Prevalence of Gastric Torsion-VMDB

Figure 1. Hospital Prevalence of Gastric Torsion-VMDB

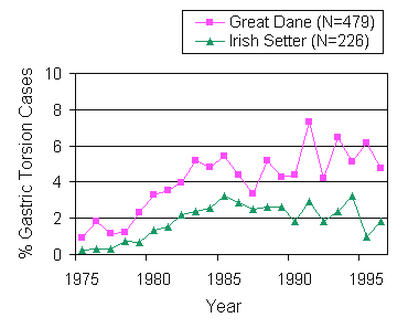

When breed-specific hospital prevalence rates were plotted for 2 high-risk breeds, i.e., Great Danes and Irish Setters, both curves showed a similar increase (Figure 2). Among 479 Great Danes, the rate rose from 0.91% in 1975 to a peak of 7.33% in 1991. Among 228 Irish Setters, the rate rose from 0.22% in 1975 to a peak of 3.25% in 1994. With relatively small numbers of dogs, the rates fluctuated from year to year, but the trend was clearly upward in both breeds. Plots for breeds with fewer dogs also showed an increasing trend over time, despite year-to-year fluctuations. These patterns indicate an environmental cause -- which remains unknown -- rather than changes in popularity of higher-risk breeds.

The breed-specific plots in Figure 2 also illustrate the high risk of bloat in these 2 breeds. Bloat may be an "uncommon" disease, but in recent years, 4 to 7 of every 100 Great Danes and 1 to 3 of every 100 Irish Setters admitted to veterinary teaching hospitals had gastric torsion.

The breed-specific plots in Figure 2 also illustrate the high risk of bloat in these 2 breeds. Bloat may be an "uncommon" disease, but in recent years, 4 to 7 of every 100 Great Danes and 1 to 3 of every 100 Irish Setters admitted to veterinary teaching hospitals had gastric torsion.

Figure 2. Hospital Prevalence of Gastric Torsion - VMDB; Great Dane & Irish Setter

Figure 2. Hospital Prevalence of Gastric Torsion - VMDB; Great Dane & Irish Setter

Heartbreak and Hope (Part 2) -- Final Analysis of the Survival and Recurrence Study

An earlier BLOAT NOTEs article (Issue 96-1) summarized results from the preliminary analysis of the survival and recurrence study, which was designed to identify the short- and long-term prognostic factors for dogs with bloat. The results of the final analysis are summarized here, and will be published in the Journal of the American Animal Hospital Association.

The dogs in this study had all been recruited for a case-control study of bloat risk factors. After clinical data forms were received from the veterinarians, owners were asked to answer questions in a phone interview. Those who agreed to participate were contacted again every few months to find out if the dog had bloated again, and if the dog was still alive.

Clinical data forms were received from 27 veterinary clinics for 159 dogs that had an acute bloat episode. Information regarding survival was obtained for 136 (85.5%) of these dogs, and they were considered to be the study population. Thirty-three (24.3%) did not survive more than 7 days after bloat onset; 26 of these 33 dogs were euthanized, 15 of them were euthanized before treatment.

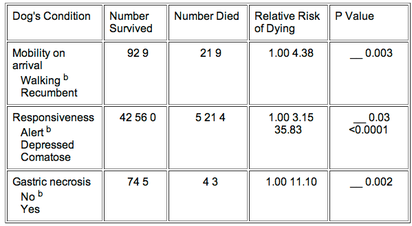

The risk of dying in the first 7 days was higher in the older dogs, but the relationship was not statistically significant. Neither the time elapsed between bloat onset and arrival at the clinic nor the time elapsed between arrival at the clinic and surgery was significantly related to 7-day survival. As shown in Table 2, the highly significant factors were the condition of the dog on arrival and the presence of gastric necrosis at surgery. If the 15 dogs that were euthanized before treatment are removed from consideration, the 7-day mortality rate was reduced to 13.2%. This is consistent with mortality rates of 15% and 17.5%, respectively, reported in 2 other series.

An earlier BLOAT NOTEs article (Issue 96-1) summarized results from the preliminary analysis of the survival and recurrence study, which was designed to identify the short- and long-term prognostic factors for dogs with bloat. The results of the final analysis are summarized here, and will be published in the Journal of the American Animal Hospital Association.

The dogs in this study had all been recruited for a case-control study of bloat risk factors. After clinical data forms were received from the veterinarians, owners were asked to answer questions in a phone interview. Those who agreed to participate were contacted again every few months to find out if the dog had bloated again, and if the dog was still alive.

Clinical data forms were received from 27 veterinary clinics for 159 dogs that had an acute bloat episode. Information regarding survival was obtained for 136 (85.5%) of these dogs, and they were considered to be the study population. Thirty-three (24.3%) did not survive more than 7 days after bloat onset; 26 of these 33 dogs were euthanized, 15 of them were euthanized before treatment.

The risk of dying in the first 7 days was higher in the older dogs, but the relationship was not statistically significant. Neither the time elapsed between bloat onset and arrival at the clinic nor the time elapsed between arrival at the clinic and surgery was significantly related to 7-day survival. As shown in Table 2, the highly significant factors were the condition of the dog on arrival and the presence of gastric necrosis at surgery. If the 15 dogs that were euthanized before treatment are removed from consideration, the 7-day mortality rate was reduced to 13.2%. This is consistent with mortality rates of 15% and 17.5%, respectively, reported in 2 other series.

Table 2. Condition of the Dog and Risk of Dying within 7 Days (a)

a Dogs that were dead on arrival are not included.

b Reference category for the risk of dying.

c P value of <0.05 is considered statistically significant.

- Point to remember: In general, once dogs make it to surgery, their chances of surviving in the near term are about 85%.

Eighteen of the 103 dogs that survived at least 7 days were lost to follow-up, but 85 were followed for periods ranging from several weeks to >3 years. Seven of these 85 dogs were euthanized or died after a bloat recurrence, 19 were euthanized or died from other causes, and 59 were surviving at the end of the study.

Seventy-four of the 85 dogs had a gastropexy after the bloat episode, while 11 did not. The median survival time was almost 3 times longer with gastropexy: 547 days for those that had gastropexy, compared with only 188 days for the 11 that did not have gastropexy (P value = 0.0001). Part of the dramatic difference in survival was due to bloat recurrence, since nearly all dogs that had a recurrence died: 6 (65.6%) of the 11 dogs that did not have gastropexy had a recurrence and 5 died. In contrast, only 3 (4.3%) of the 74 dogs that had gastropexy had a recurrence (2 died). Similar differences in recurrence rates have been reported in other recent series.

Seventy-four of the 85 dogs had a gastropexy after the bloat episode, while 11 did not. The median survival time was almost 3 times longer with gastropexy: 547 days for those that had gastropexy, compared with only 188 days for the 11 that did not have gastropexy (P value = 0.0001). Part of the dramatic difference in survival was due to bloat recurrence, since nearly all dogs that had a recurrence died: 6 (65.6%) of the 11 dogs that did not have gastropexy had a recurrence and 5 died. In contrast, only 3 (4.3%) of the 74 dogs that had gastropexy had a recurrence (2 died). Similar differences in recurrence rates have been reported in other recent series.

- Point to remember: Therapy for shock and gastric decompression should be considered only as first aid for dogs with bloat. Some form of gastropexy is needed to prevent a recurrence. After gastropexy, bloat recurrence is rare and most dogs lead normal lives.

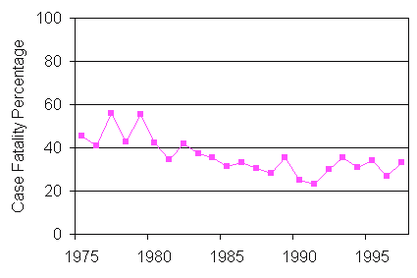

Figure 3. Case Fatality Rate for GDV

Figure 3. Case Fatality Rate for GDV

Waiting for Trouble: Age at Bloat Onset

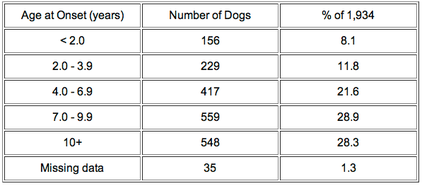

Designing a study of risk factors for diseases of aging, such as bloat or cancer, offers special challenges because of the long wait for the disease to appear. (Good news for the dog, bad news for the researchers!) Although bloat can occur in young dogs, the risk increases significantly, as dogs grow older. A retrospective study of records in the VMDB was conducted for 1,934 dogs treated in 12 veterinary teaching hospitals in 1980-1989.1 Overall, 78.8% of the dogs were at least 4 years old before they bloated.

Designing a study of risk factors for diseases of aging, such as bloat or cancer, offers special challenges because of the long wait for the disease to appear. (Good news for the dog, bad news for the researchers!) Although bloat can occur in young dogs, the risk increases significantly, as dogs grow older. A retrospective study of records in the VMDB was conducted for 1,934 dogs treated in 12 veterinary teaching hospitals in 1980-1989.1 Overall, 78.8% of the dogs were at least 4 years old before they bloated.

Table 3. Age at Onset of Bloat in 1,934 Dogs

The risk of bloat was more than twice as high in dogs 7.0-9.9 years old as in dogs 2.0-3.9 years old, and more than 3 times as high in dogs age 10 or older.

In the case-control study described in previous BLOAT NOTEs issues, 101 dogs with bloat were treated between January 1992 and June 1995.2 Their mean age at onset was 6.9 years (standard deviation ± 3.2 years). In a series of 160 dogs treated for bloat at the University of Utrecht, the Netherlands, in 1984-1989, the average age at onset was 6.8 years (range 10 months - 13.6 years).3 In a series of 134 dogs treated at the School of Veterinary Medicine in Hanover, Germany, in January 1988 - April 1991, the age at onset ranged from 2 to 17 years, but 70.2% of the dogs were 7-12 years old at onset.4 In a series of 103 dogs treated at the Norwegian College of Veterinary Medicine on Oslo, Norway, in 1985-1989, the age at onset averaged 7.2 years (range 1-15 years); 58.3% of the dogs were 6.1-12 years old when they bloated.5

A prospective study requires that dogs be healthy at the beginning and then be followed forward in time to determine if disease occurs. If a prospective study of bloat were designed to have all dogs enrolled as pups, the follow-up would have to continue for >6 years to get an adequate picture of bloat risk. Dogs of all ages (over 6 months) were enrolled in Purdue's prospective study. This should increase the chances of seeing enough cases that accurate conclusions can be drawn about bloat risk factors.

References

LT Glickman et al.: J Am Vet Med Assoc 204(9):1465-1471, 1994.

LT Glickman et al.: J Am Animal Hosp Assoc 33:197-204, 1997.

FJ van Sluijs: Tidschrift voor Diergeneeskunde 116(3):112-121, 1991.

A Meyer-Lindenberg et al.: J Am Vet Med Assoc 203(9):1303-1307, 1993.

AV Eggertsdottir, L Moe: Acta Vet Scand 36:175-184, 1995.

How Long Will They Live?

All owners would like to know how long their dogs are likely to live, but researchers need large amounts of detailed information on longevity to help understand the causes of disease and the effects of treatment. For example, lifetime histories are needed to complete family studies, i.e., studies of genetic influences like the Irish Setter family study of bloat described in the section entitled 'All in the Family.' How long will the litters have to be followed to be sure which dogs bloat?

The VMDB offers opportunities to evaluate the average age at death of dogs admitted to US veterinary teaching hospitals. Drs. Deeb and Wolf compared 6 giant breeds and 7 small breeds in terms of the age at death and the age an which various diseases were diagnosed at necropsy.1 Dr. Patronek and co-workers at Purdue explored the effect of breed and body weight on longevity and developed a method to standardize the chronological age of dogs in human year equivalents.2 The problem in extrapolating average age at death determined in VMDB studies to all dogs in a breed is that dogs admitted to veterinary teaching hospitals are likely to have serious diseases.

Another recent study analyzed data from >222,000 Swedish dogs enrolled in life insurance programs in 1992-1993.3 The paper presented useful data on breed-specific mortality rates and causes of death, but did not include the average age at death.

The best estimates of average lifespan may need to come from breed club surveys -- which offer challenges of their own.

References

BJ Deeb, NS Wolf: Vet Med (Supplement) 93:701-713, 1994.

GJ Patronek et al.: J Gerontol Biol Sci 52A(3):B171-B178, 1997.

BN Bonnett et al.: Vet Record, 141(2):40-44, July 12, 1997.

Designing Breed Health Surveys

Breed clubs that decide to survey health problems in their breed have a laudable goal. A survey can document which health problems are common to the breed. This allows the club to focus its research and education efforts. Publicity about the results provides a forum for discussion among breeders about the common problems.

But which owners do you survey? All the club members? Some of the club members? A sample of all owners who have registered dogs of the breed? How do you get enough owners to participate so that the responses represent the breed? What happens when only 10% respond? Are the respondents owners whose dogs have more health problems? Fewer health problems? (And what about confidentiality?)

Which dogs do you ask about? All of an owner's current dogs? If an owner has dozens, do you ask about some of them? About dogs that died 5 years ago? 10 years ago?

Is it better to use written questionnaires or phone interviews? What type of questions should you ask? About all diseases? A few diseases? Should you record only diseases that have been diagnosed by a veterinarian? How will the data be organized and analyzed? Who will write the final report?

A breed club considering a survey is strongly advised to consult a veterinary epidemiologist, particularly one who has experience in studying the epidemiology of diseases of companion animals. The time to consult is at the beginning, before the survey and questionnaires are designed.

Dr. Margaret Slater published the first paper in the veterinary medical literature evaluating methods for canine breed surveys.1 Earlier, Dr. W. Jean Dodds summarized results of a number of breed surveys.

Currently, Larry and Nita Glickman are working with the Health Committee of the Irish Setter Club of America (Mrs. Connie Vanacore, Chairman) on a survey of longevity and health problems in Irish Setters. They are also trying to relate the physical characteristics and diet of the dogs with specific health problems. They stress that at least as much time goes into developing the questionnaire as conducting the actual survey. It is important to define objectives and know what questions you want to answer before collecting the data. Data analysis requires knowledge of dogs and their management as well as statistical and computer skills. Interpretation of the findings should be a team effort, and include input from the breed club, veterinarians, and statisticians.

References

M Slater: Preventive Vet Med 28:69-79, 1996

WJ Dodds: Adv Vet Sci Comp Med 39:29-96, 1995

All in the Family (Part 4)

We continue to follow a family of Irish Setters in which several dogs have already bloated. This family study is another attempt to better understand genetic influences on bloat, which can cluster within certain families (familial bloat) or occur in unrelated animals (sporadic bloat). Geneticist Dr. Robert Schaible and Irish Setter breeder Jan Ziech collaborated with the Purdue Bloat Research Team in this study 1

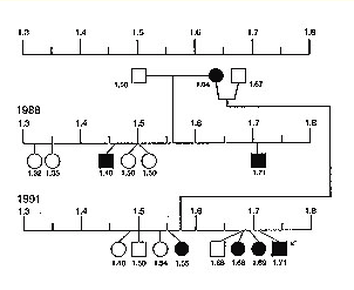

Measurement data and bloat histories were collected for all but 1 of 15 surviving pups in 2 litters, whelped in 1988 and 1991, respectively, that had the same dam but different sires. The parents' measurements and bloat histories were obtained. The pedigree was plotted on a scale of chest depth/width ratios (Figure 4). The ratios in this family are spread across a wide range of values for Irish Setters enrolled in the ongoing prospective study.

The pattern suggested that incomplete dominance of a major gene is the mode of inheritance of chest depth/width ratio. After the study was published, another pup in the 1991 litter bloated (indicated by arrow in pedigree). The data support the hypothesis that dogs with a deeper chest relative to width are at greater risk of developing bloat than dogs of the same breed with smaller chest depth/width ratios. The pattern for this family will not be complete, however, until all dogs have been followed throughout their lifetime.

In the case-control study described in previous BLOAT NOTEs issues, 101 dogs with bloat were treated between January 1992 and June 1995.2 Their mean age at onset was 6.9 years (standard deviation ± 3.2 years). In a series of 160 dogs treated for bloat at the University of Utrecht, the Netherlands, in 1984-1989, the average age at onset was 6.8 years (range 10 months - 13.6 years).3 In a series of 134 dogs treated at the School of Veterinary Medicine in Hanover, Germany, in January 1988 - April 1991, the age at onset ranged from 2 to 17 years, but 70.2% of the dogs were 7-12 years old at onset.4 In a series of 103 dogs treated at the Norwegian College of Veterinary Medicine on Oslo, Norway, in 1985-1989, the age at onset averaged 7.2 years (range 1-15 years); 58.3% of the dogs were 6.1-12 years old when they bloated.5

A prospective study requires that dogs be healthy at the beginning and then be followed forward in time to determine if disease occurs. If a prospective study of bloat were designed to have all dogs enrolled as pups, the follow-up would have to continue for >6 years to get an adequate picture of bloat risk. Dogs of all ages (over 6 months) were enrolled in Purdue's prospective study. This should increase the chances of seeing enough cases that accurate conclusions can be drawn about bloat risk factors.

References

LT Glickman et al.: J Am Vet Med Assoc 204(9):1465-1471, 1994.

LT Glickman et al.: J Am Animal Hosp Assoc 33:197-204, 1997.

FJ van Sluijs: Tidschrift voor Diergeneeskunde 116(3):112-121, 1991.

A Meyer-Lindenberg et al.: J Am Vet Med Assoc 203(9):1303-1307, 1993.

AV Eggertsdottir, L Moe: Acta Vet Scand 36:175-184, 1995.

How Long Will They Live?

All owners would like to know how long their dogs are likely to live, but researchers need large amounts of detailed information on longevity to help understand the causes of disease and the effects of treatment. For example, lifetime histories are needed to complete family studies, i.e., studies of genetic influences like the Irish Setter family study of bloat described in the section entitled 'All in the Family.' How long will the litters have to be followed to be sure which dogs bloat?

The VMDB offers opportunities to evaluate the average age at death of dogs admitted to US veterinary teaching hospitals. Drs. Deeb and Wolf compared 6 giant breeds and 7 small breeds in terms of the age at death and the age an which various diseases were diagnosed at necropsy.1 Dr. Patronek and co-workers at Purdue explored the effect of breed and body weight on longevity and developed a method to standardize the chronological age of dogs in human year equivalents.2 The problem in extrapolating average age at death determined in VMDB studies to all dogs in a breed is that dogs admitted to veterinary teaching hospitals are likely to have serious diseases.

Another recent study analyzed data from >222,000 Swedish dogs enrolled in life insurance programs in 1992-1993.3 The paper presented useful data on breed-specific mortality rates and causes of death, but did not include the average age at death.

The best estimates of average lifespan may need to come from breed club surveys -- which offer challenges of their own.

References

BJ Deeb, NS Wolf: Vet Med (Supplement) 93:701-713, 1994.

GJ Patronek et al.: J Gerontol Biol Sci 52A(3):B171-B178, 1997.

BN Bonnett et al.: Vet Record, 141(2):40-44, July 12, 1997.

Designing Breed Health Surveys

Breed clubs that decide to survey health problems in their breed have a laudable goal. A survey can document which health problems are common to the breed. This allows the club to focus its research and education efforts. Publicity about the results provides a forum for discussion among breeders about the common problems.

But which owners do you survey? All the club members? Some of the club members? A sample of all owners who have registered dogs of the breed? How do you get enough owners to participate so that the responses represent the breed? What happens when only 10% respond? Are the respondents owners whose dogs have more health problems? Fewer health problems? (And what about confidentiality?)

Which dogs do you ask about? All of an owner's current dogs? If an owner has dozens, do you ask about some of them? About dogs that died 5 years ago? 10 years ago?

Is it better to use written questionnaires or phone interviews? What type of questions should you ask? About all diseases? A few diseases? Should you record only diseases that have been diagnosed by a veterinarian? How will the data be organized and analyzed? Who will write the final report?

A breed club considering a survey is strongly advised to consult a veterinary epidemiologist, particularly one who has experience in studying the epidemiology of diseases of companion animals. The time to consult is at the beginning, before the survey and questionnaires are designed.

Dr. Margaret Slater published the first paper in the veterinary medical literature evaluating methods for canine breed surveys.1 Earlier, Dr. W. Jean Dodds summarized results of a number of breed surveys.

Currently, Larry and Nita Glickman are working with the Health Committee of the Irish Setter Club of America (Mrs. Connie Vanacore, Chairman) on a survey of longevity and health problems in Irish Setters. They are also trying to relate the physical characteristics and diet of the dogs with specific health problems. They stress that at least as much time goes into developing the questionnaire as conducting the actual survey. It is important to define objectives and know what questions you want to answer before collecting the data. Data analysis requires knowledge of dogs and their management as well as statistical and computer skills. Interpretation of the findings should be a team effort, and include input from the breed club, veterinarians, and statisticians.

References

M Slater: Preventive Vet Med 28:69-79, 1996

WJ Dodds: Adv Vet Sci Comp Med 39:29-96, 1995

All in the Family (Part 4)

We continue to follow a family of Irish Setters in which several dogs have already bloated. This family study is another attempt to better understand genetic influences on bloat, which can cluster within certain families (familial bloat) or occur in unrelated animals (sporadic bloat). Geneticist Dr. Robert Schaible and Irish Setter breeder Jan Ziech collaborated with the Purdue Bloat Research Team in this study 1

Measurement data and bloat histories were collected for all but 1 of 15 surviving pups in 2 litters, whelped in 1988 and 1991, respectively, that had the same dam but different sires. The parents' measurements and bloat histories were obtained. The pedigree was plotted on a scale of chest depth/width ratios (Figure 4). The ratios in this family are spread across a wide range of values for Irish Setters enrolled in the ongoing prospective study.

The pattern suggested that incomplete dominance of a major gene is the mode of inheritance of chest depth/width ratio. After the study was published, another pup in the 1991 litter bloated (indicated by arrow in pedigree). The data support the hypothesis that dogs with a deeper chest relative to width are at greater risk of developing bloat than dogs of the same breed with smaller chest depth/width ratios. The pattern for this family will not be complete, however, until all dogs have been followed throughout their lifetime.

Pedigree of parents and pups in 2 Irish Setter litters, with chest depth/width ratio for each dog. Circles indicate females, squares indicate males. Solid symbols indicate dogs that have bloated. (Modified from Schaible et al)

Reference

RH Schaible et al.: J Am Animal Hosp Assoc 33:379-383, 1997

Recurrent/Chronic Bloat

Some dogs have repeated episodes of gastric dilatation, with or without volvulus. Occasionally, this will occur even after gastropexy. In other dogs, chronic volvulus, with or without dilatation, can be demonstrated on abdominal radiographs. Can these uncommon, but very troublesome, conditions help us understand the mechanism of bloat?

Chronic volvulus is not usually the emergency of acute bloat, and, if the malposition of the stomach is intermittent rather than constant it can be difficult to diagnose. The clinical signs include intermittent vomiting, with or without abdominal distention and/or pain; lethargy; anorexia; and weight loss. Restoring the stomach to its normal position and performing a permanent gastropexy usually cures the condition.

Swallowing air (aerophagia) has long been suspected as a risk factor for acute bloat, but since acute bloat strikes without warning, it would very difficult to demonstrate a relationship. The situation may be different in dogs with frequently recurring gastric dilatation or chronic volvulus. In 1987 Drs. van Sluijs and Wolvekamp at the University of Utrecht, the Netherlands, described 6 large- or giant-breed dogs with multiple (3-10) episodes of gastric dilatation in which aerophagia "had apparently become a habit and a major cause for their illness." In 5 dogs, described by their owners as "greedy eaters," dilatation was seen only after meals; another dog also had dilatation between meals during episodes of nervousness and hyperventilation. Symptoms included belching and flatulence in all 6 dogs, vomiting in 4, and diarrhea in 2 of those with vomiting.

The episodes usually resolved spontaneously, but the owners of 3 dogs had repeatedly passed a gastric tube, and another dog had twice undergone surgical repositioning and decompression. When examined by X-ray, 2 of the dogs had gastric volvulus, 2 had gastric dilatation without volvulus, and all 6 had an increased amount of gas in the intestinal tract.

Four of the dogs were euthanized. The only dog who really fared well was a 5-month-old St. Bernard with dilatation but not volvulus, whose "greedy eating habits" were changed by behavioral therapy. The owner offered all food manually, praising the dog for careful handling of the food and "punishing greedy consumption by a tap on the nose." Within 2 weeks the dog had learned to handle his food carefully and to avoid swallowing air. During 6 months' follow-up the dog had no more episodes. (This may be the only report in the veterinary literature of successful treatment of chronic dilatation with behavioral modification.)

The authors noted that, since the recurrence rate of gastric dilatation-volvulus is reduced so drastically by gastropexy. the majority of dogs apparently have aerophagia "of a more incidental nature" than the persistent type in this series of 6 dogs.

Every Little Swallow--

In the normal dog, swallowing begins a well-integrated pattern of esophageal activity to transport food from the back of the mouth (pharynx) to the stomach. The upper esophageal sphincter, which normally remains closed to keep food from straying into the trachea, opens to allow the food bolus into the esophagus. A wave of muscle contraction (primary peristalsis) moves the food bolus toward the stomach. Distention of the esophagus causes a secondary peristaltic wave to take the food bolus the rest of the way.

The lower esophageal sphincter (gastroesophageal sphincter), which is normally closed to prevent splashback (reflux) of acidic stomach contents into the esophagus, relaxes enough to allow the food bolus into the stomach.

Studies of abnormalities in these coordinated movements require contrast radiography and fluoroscopy.

In an abstract, Drs. van Sluijs and Wolvekamp reported videofluororadiographic studies of 15 dogs with recurrent gastric dilatation-volvulus.2 The dogs were placed in front of a fluoroscopy camera and fed a barium meal. Nine dogs had 1 or more disturbances of the swallowing process: abnormal formation of a food bolus in the pharynx in 2, decreased peristalsis of the esophagus in 6; and gastroesophageal reflux in 3. "Aerophagy occurred mainly when primary esophageal peristalsis failed to transport a food bolus to the stomach." The authors concluded that "recurrent GDV may be associated with abnormal esophageal motility and that impaired transport of food through the esophagus may induce aerophagy."

Further radiographic studies of esophageal anatomy and function in chronic bloat are needed to confirm and extend these observations, and might also offer insight into the role of the esophagus in the acute condition. We are exploring the feasibility of conducting such a study at Purdue.

References

FJ van Sluijs: Gastric Dilatation-Volvulus in the Dog, Thesis, Faculty of Vet. Med., Univ. of Utrecht, the Netherlands, 1987. Chap. III, pp.77-88.

FJ van Sluijs, WTC Wolvekamp: Vet Surg 22(3):250, 1993

@ Editor's Corner --

Some dogs have repeated episodes of gastric dilatation, with or without volvulus. Occasionally, this will occur even after gastropexy. In other dogs, chronic volvulus, with or without dilatation, can be demonstrated on abdominal radiographs. Can these uncommon, but very troublesome, conditions help us understand the mechanism of bloat?

Chronic volvulus is not usually the emergency of acute bloat, and, if the malposition of the stomach is intermittent rather than constant it can be difficult to diagnose. The clinical signs include intermittent vomiting, with or without abdominal distention and/or pain; lethargy; anorexia; and weight loss. Restoring the stomach to its normal position and performing a permanent gastropexy usually cures the condition.

Swallowing air (aerophagia) has long been suspected as a risk factor for acute bloat, but since acute bloat strikes without warning, it would very difficult to demonstrate a relationship. The situation may be different in dogs with frequently recurring gastric dilatation or chronic volvulus. In 1987 Drs. van Sluijs and Wolvekamp at the University of Utrecht, the Netherlands, described 6 large- or giant-breed dogs with multiple (3-10) episodes of gastric dilatation in which aerophagia "had apparently become a habit and a major cause for their illness." In 5 dogs, described by their owners as "greedy eaters," dilatation was seen only after meals; another dog also had dilatation between meals during episodes of nervousness and hyperventilation. Symptoms included belching and flatulence in all 6 dogs, vomiting in 4, and diarrhea in 2 of those with vomiting.

The episodes usually resolved spontaneously, but the owners of 3 dogs had repeatedly passed a gastric tube, and another dog had twice undergone surgical repositioning and decompression. When examined by X-ray, 2 of the dogs had gastric volvulus, 2 had gastric dilatation without volvulus, and all 6 had an increased amount of gas in the intestinal tract.

Four of the dogs were euthanized. The only dog who really fared well was a 5-month-old St. Bernard with dilatation but not volvulus, whose "greedy eating habits" were changed by behavioral therapy. The owner offered all food manually, praising the dog for careful handling of the food and "punishing greedy consumption by a tap on the nose." Within 2 weeks the dog had learned to handle his food carefully and to avoid swallowing air. During 6 months' follow-up the dog had no more episodes. (This may be the only report in the veterinary literature of successful treatment of chronic dilatation with behavioral modification.)

The authors noted that, since the recurrence rate of gastric dilatation-volvulus is reduced so drastically by gastropexy. the majority of dogs apparently have aerophagia "of a more incidental nature" than the persistent type in this series of 6 dogs.

Every Little Swallow--

In the normal dog, swallowing begins a well-integrated pattern of esophageal activity to transport food from the back of the mouth (pharynx) to the stomach. The upper esophageal sphincter, which normally remains closed to keep food from straying into the trachea, opens to allow the food bolus into the esophagus. A wave of muscle contraction (primary peristalsis) moves the food bolus toward the stomach. Distention of the esophagus causes a secondary peristaltic wave to take the food bolus the rest of the way.

The lower esophageal sphincter (gastroesophageal sphincter), which is normally closed to prevent splashback (reflux) of acidic stomach contents into the esophagus, relaxes enough to allow the food bolus into the stomach.

Studies of abnormalities in these coordinated movements require contrast radiography and fluoroscopy.

In an abstract, Drs. van Sluijs and Wolvekamp reported videofluororadiographic studies of 15 dogs with recurrent gastric dilatation-volvulus.2 The dogs were placed in front of a fluoroscopy camera and fed a barium meal. Nine dogs had 1 or more disturbances of the swallowing process: abnormal formation of a food bolus in the pharynx in 2, decreased peristalsis of the esophagus in 6; and gastroesophageal reflux in 3. "Aerophagy occurred mainly when primary esophageal peristalsis failed to transport a food bolus to the stomach." The authors concluded that "recurrent GDV may be associated with abnormal esophageal motility and that impaired transport of food through the esophagus may induce aerophagy."

Further radiographic studies of esophageal anatomy and function in chronic bloat are needed to confirm and extend these observations, and might also offer insight into the role of the esophagus in the acute condition. We are exploring the feasibility of conducting such a study at Purdue.

References

FJ van Sluijs: Gastric Dilatation-Volvulus in the Dog, Thesis, Faculty of Vet. Med., Univ. of Utrecht, the Netherlands, 1987. Chap. III, pp.77-88.

FJ van Sluijs, WTC Wolvekamp: Vet Surg 22(3):250, 1993

@ Editor's Corner --

- BLOAT NOTEs is not copyrighted and may be freely reproduced, with acknowledgment of the source.

- Our thanks to those who completed the survey regarding topics of interest for a future canine health newsletter.

- Those readers wanting more information about bloat research at Purdue can find us on the Internet at the following address: www.vet.purdue.edu/depts/vad/cae