WHAT POPULATION GENETICS CAN TELL YOU ABOUT A BREED:

THE ICELANDIC SHEEPDOG

The Icelandic Sheepdog is like many other rare dog breeds -

1) It was founded with a relatively small number of dogs (36);

2) It became a registered breed fairly recently (~1955);

3) For much of its history as a registered breed the total population was small (< ~500 dogs until about 1990);

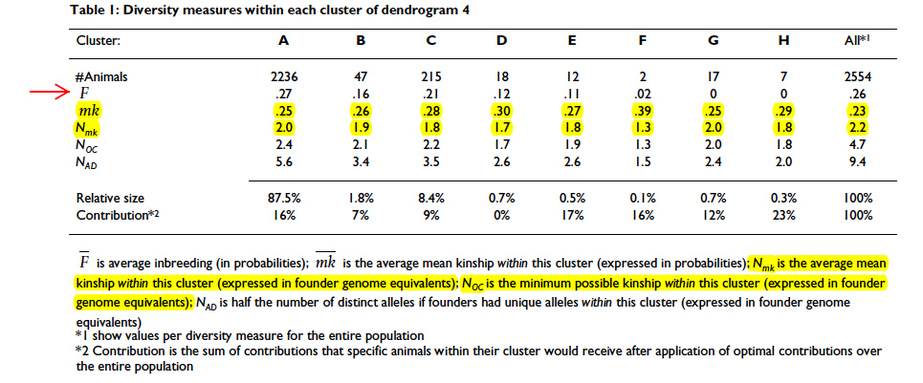

4) There has been a rapid increase in registrations in recent years as the breed has gained a following and been introduced to new countries (see Figure 1);

5) At the time of the study, the current population numbered about 2500 dogs, many times the size of the founding population.

A small, closed population will inevitably suffer from inbreeding, resulting in inbreeding depression which is reflected in reduced resistance to disease, reproductive problems (reduced fertility, smaller offspring, smaller litter sizes, higher mortality, etc). Also, with loss of genetic diversity in breeding populations, there will likely be an increase in the incidence of inherited disorders, because it becomes more likely that an individual will just by chance be homozygous for a deleterious allele.

Knowing that breeding of Icelandic Sheepdogs had not been managed in any way as the breed grew in popularity, Oliehoek and his colleagues suspected that an analysis of the breed might reveal some evidence of significant inbreeding.

They gathered together the pedigrees for all the registered dogs in the world back to founders (a total of 4680 current and ancestor dogs) and subjected them to special analyses that were able to reveal things about the breed that would have been difficult or impossible to learn any other way.

1) It was founded with a relatively small number of dogs (36);

2) It became a registered breed fairly recently (~1955);

3) For much of its history as a registered breed the total population was small (< ~500 dogs until about 1990);

4) There has been a rapid increase in registrations in recent years as the breed has gained a following and been introduced to new countries (see Figure 1);

5) At the time of the study, the current population numbered about 2500 dogs, many times the size of the founding population.

A small, closed population will inevitably suffer from inbreeding, resulting in inbreeding depression which is reflected in reduced resistance to disease, reproductive problems (reduced fertility, smaller offspring, smaller litter sizes, higher mortality, etc). Also, with loss of genetic diversity in breeding populations, there will likely be an increase in the incidence of inherited disorders, because it becomes more likely that an individual will just by chance be homozygous for a deleterious allele.

Knowing that breeding of Icelandic Sheepdogs had not been managed in any way as the breed grew in popularity, Oliehoek and his colleagues suspected that an analysis of the breed might reveal some evidence of significant inbreeding.

They gathered together the pedigrees for all the registered dogs in the world back to founders (a total of 4680 current and ancestor dogs) and subjected them to special analyses that were able to reveal things about the breed that would have been difficult or impossible to learn any other way.

They found that not only were the dogs extremely inbred, but the situation of the breed was dire.

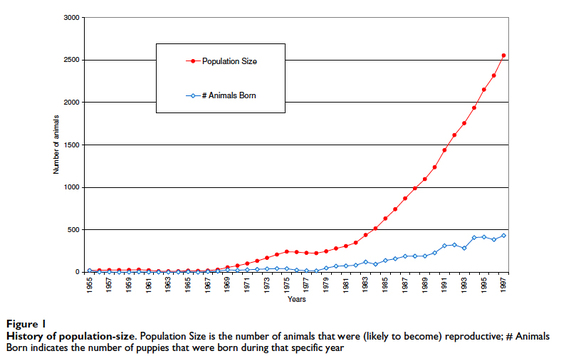

1) In just the first 10 years after registration, the breed lost more than 50% of its initial genetic diversity (Figure 2);

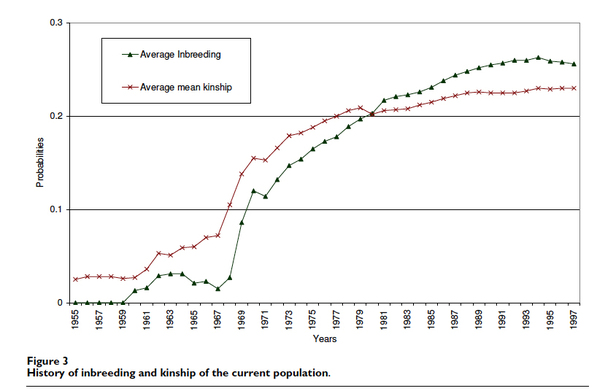

2) The astonishing decline in genetic diversity was a consequence of breeding practices that resulted in increasing levels of inbreeding over time (kinship is a measure of overall genetic similarity between two animals);

3) At the time of the study, the entire worldwide population of 2554 dogs had the genetic diversity expected from only 2.2 founders;

4) The average coefficient of inbreeding of the existing dogs was about 25%, and the entire population was as closely related as siblings;

This is grim news. Starting with 36 (supposedly) unrelated dogs, inbreeding has reduced the breed to the genetic equivalent of about 2 individuals as closely related as siblings. To save the breed from potential extinction as a consequence of inbreeding, the genetic diversity in the population(s) of breeding dogs needs to increase.

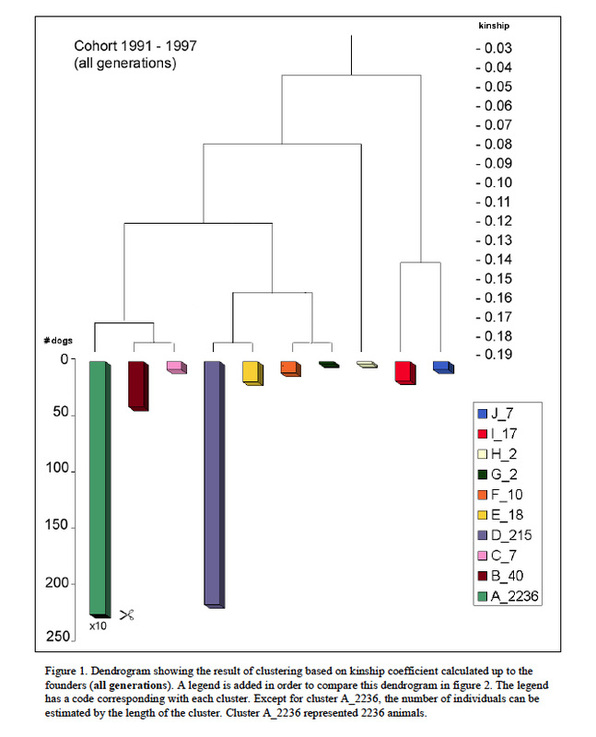

Using a very clever analytical technique called "cluster analysis", Oliehoek was able to sort the existing dogs into groups of individuals that were similar genetically. He was able to identify 8 groups, two large ones, four of modest size, and two that were very small. You can see these in Figure 6. Note that the longest bar is really 10 times longer than depicted so the graph would fit on the page. So it's a VERY big group – in fact, 85% of the entire population. What this means is that the breed population is not genetically homogeneous. That is, there are little subpopulations of animals in different countries that carry alleles not found in the other groups.

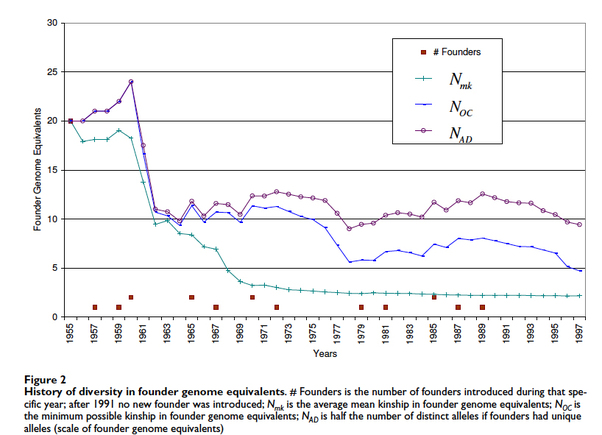

In the summary table below, the average degree of inbreeding ("F" in the table) in the population as a whole ("All") was 26% (0.26).

Average mean kinship (mk) is the degree of relatedness of the animals; a value of 0.25 would be the equivalent of full siblings.

The two statistics using founder genome equivalents (Nmk and Noc), indicate that the entire population has the genetic diversity that would be expected to result if there had been only two founders.

Average mean kinship (mk) is the degree of relatedness of the animals; a value of 0.25 would be the equivalent of full siblings.

The two statistics using founder genome equivalents (Nmk and Noc), indicate that the entire population has the genetic diversity that would be expected to result if there had been only two founders.

In a carefully managed breeding program, the little puddles of diversity in all the subpopulations could be used to bring the genetic diversity in the breeding population from the equivalent of 2.2 founders up to as much as 4.7 (which is still extremely low).

The good news is that when this study was published, the Icelandic Sheepdog breeders used this information to modify breeding strategies to protect the smaller populations of genetically unique animals from extinction, and minimize the additional loss of genetic diversity from the breed.

The good news is that when this study was published, the Icelandic Sheepdog breeders used this information to modify breeding strategies to protect the smaller populations of genetically unique animals from extinction, and minimize the additional loss of genetic diversity from the breed.

You can download a copy of the original publication here -

Oliehoek, PA, P Bijma, & A van der Meijden. 2009. History and structure of the closed pedigreed population of Icelandic Sheepdogs. (PDF download)

Oliehoek, PA, P Bijma, & A van der Meijden. 2009. History and structure of the closed pedigreed population of Icelandic Sheepdogs. (PDF download)