POPULATION GENETICS OF NOVA SCOTIA DUCK TOLLING RETRIEVERS

There is an astonishing amount of information hiding in a basic pedigree database that you can extract using the tools of population genetics. The size of the original gene pool for the breed, how much genetic diversity has been lost over the generations, the breeding strategies that have been used, and the current genetic status of the breed. You can learn from your breed's past, and you can also design breeding strategies to protect the existing gene pool. This is information every breeder should have for their breed, and they should know how to use it.

Here's a great example of a population genetic analysis of the pedigree database of a relatively rare breed, the Nova Scotia Duck Tolling Retriever. A similar analysis can be performed using the pedigree data of any breed!

The Toller was developed as a gun dog in Nova Scotia, Canada. The breed has a behavioral trait called tolling that lures ducks and geese towards shore to be within shotgun range, hence their nickname, "Tollers".

Summary

Here is what we will learn from the analysis of the data below:

1) The entire breed descends from about 20 founder dogs

2) The database of the breed contains more than 28,600 dogs (through 2010)

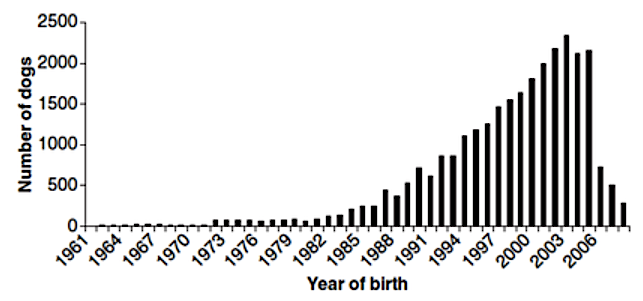

3) There was a surge in popularity beginning in the 1980s

4) Over the course of the breed's history, only a small fraction of the available dogs produced offspring

5) Inbreeding increased rapidly after 1960 and has remained higher than 25%

6) The effective population size of the current population is only 27 dogs

7) The population in 2010 had the genetic diversity of only 2.1 dogs (and it can only go down)

8) On average, the animals in the breed are more closely related than full siblings

Founders

All Tollers today can trace their origin to 9 dogs, 6 of which were full siblings. These dogs produced 81 registered offspring, 30 of which were bred. One of the founder dogs produced two puppies that were never bred, so today's breed descends from only 4 original lines. The breed was first recognized by the Canadian Kennel Club in 1945, and in 2003 it was recognized by the AKC.

An assessment of the genetics of the global population (17 countries) of Tollers was published in 2010. The total number of dogs in the database (1931-2008) was 28,668, and of these 22 were designated as founders because their parents were unknown. Of these, 18 had offspring more remote than the 6th generation. This pedigree information was used to reconstruct the genetic history of the breed as well as its current genetic status. The "current" population (the living, potentially reproductive animals) was defined in the study as those born between 1999 and 2008.

Here's a great example of a population genetic analysis of the pedigree database of a relatively rare breed, the Nova Scotia Duck Tolling Retriever. A similar analysis can be performed using the pedigree data of any breed!

The Toller was developed as a gun dog in Nova Scotia, Canada. The breed has a behavioral trait called tolling that lures ducks and geese towards shore to be within shotgun range, hence their nickname, "Tollers".

Summary

Here is what we will learn from the analysis of the data below:

1) The entire breed descends from about 20 founder dogs

2) The database of the breed contains more than 28,600 dogs (through 2010)

3) There was a surge in popularity beginning in the 1980s

4) Over the course of the breed's history, only a small fraction of the available dogs produced offspring

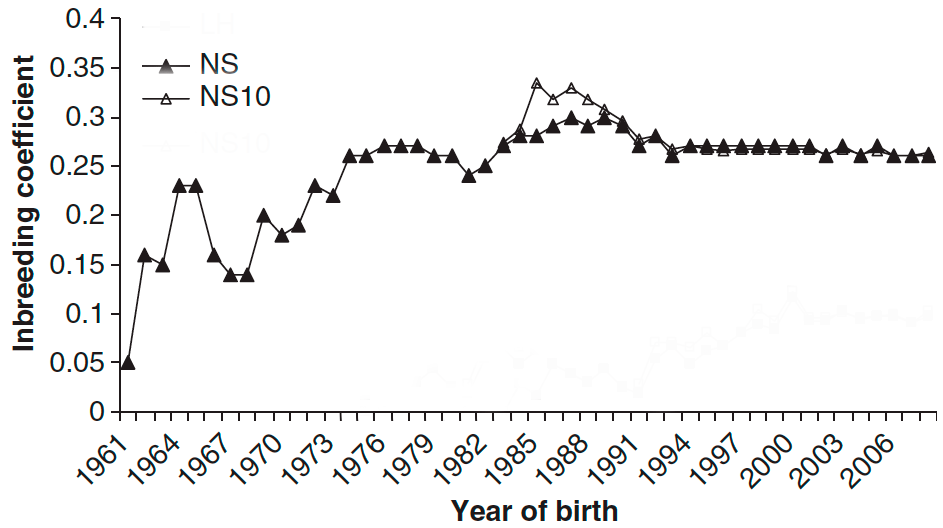

5) Inbreeding increased rapidly after 1960 and has remained higher than 25%

6) The effective population size of the current population is only 27 dogs

7) The population in 2010 had the genetic diversity of only 2.1 dogs (and it can only go down)

8) On average, the animals in the breed are more closely related than full siblings

Founders

All Tollers today can trace their origin to 9 dogs, 6 of which were full siblings. These dogs produced 81 registered offspring, 30 of which were bred. One of the founder dogs produced two puppies that were never bred, so today's breed descends from only 4 original lines. The breed was first recognized by the Canadian Kennel Club in 1945, and in 2003 it was recognized by the AKC.

An assessment of the genetics of the global population (17 countries) of Tollers was published in 2010. The total number of dogs in the database (1931-2008) was 28,668, and of these 22 were designated as founders because their parents were unknown. Of these, 18 had offspring more remote than the 6th generation. This pedigree information was used to reconstruct the genetic history of the breed as well as its current genetic status. The "current" population (the living, potentially reproductive animals) was defined in the study as those born between 1999 and 2008.

|

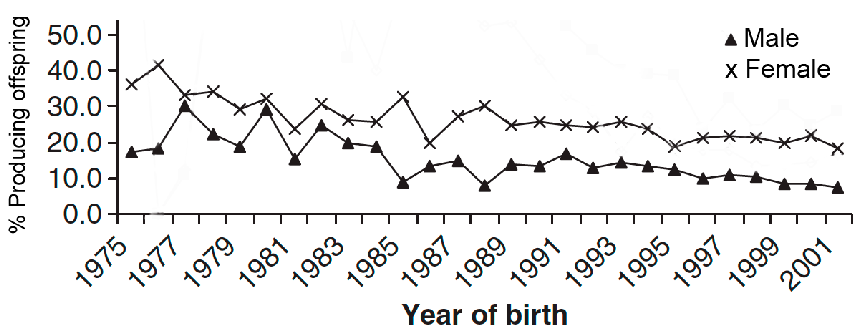

Breeding

Over this period, breeding was apparently very selective, with less than 50% of the populations of each sex producing offspring. As popularity began to increase in the 1985, selectivity increased; the fraction of females that produced offspring fell from 30%+ to about 20%, and for males it dropped from 20% or more to less than 10%. As a consequence of this, only 13% of the historical breed population produced offspring. |

|

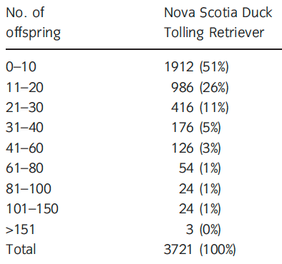

Popular sires

There is evidence of popular sires in the tallies of offspring. Although most dogs produced fewer than 10 puppies (1,912, or 51%), 48 dogs (3%) produced 60-150 offspring and 3 (presumably male) dogs (< 1%) sired more than 151 puppies. NS10 are data for dogs with at least 10 complete generations of pedigree data. Missing data will reduce the estimated level of inbreeding. |

|

Inbreeding

In 1960, the average level of inbreeding in the dogs born that year was less than 5%, but from there it increased and was about 15% by 1968, and more than 25% ten years later. Average inbreeding has continued to be more than 25% through about 2010. The inbreeding calculated using only dogs with 10 complete pedigree generations was 33% in 1985. The rate of inbreeding over this entire period was 1.87%. The present level of inbreeding (from 10 generations of pedigree data, so this could be substantial underestimate) for a selection of 9 currently competing dogs (2014-2015, USA), the average 10 generation COI was 27.2%, with a range from 23.3% to 31.9%. |

|

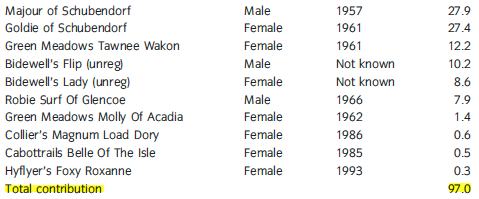

Ancestor contributions to the current population Most (97%) of the genetic diversity in the current population could be accounted for by only 10 individuals, 3 of which were born since 1985. Two dogs, a male and a female (born 1957 and 1961, respectively) accounted for more than 55% of the total genetic diversity in the current population. |

Population genetic statistics

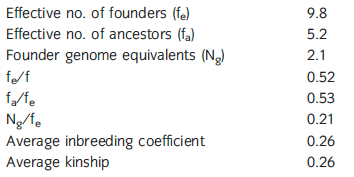

Statistics for the current population used in the study (1999-2008) provide information about both history and genetic health of the breed.

Statistics for the current population used in the study (1999-2008) provide information about both history and genetic health of the breed.

|

Remember that the "effective number of founders" (fe) is the number of equally contributing founder animals that would produce the current level of genetic diversity, and "effective number of ancestors" (fa) is the number of ancestors (founders or not) needed to account for the current level of genetic diversity.

For the population of dogs born between 1999 and 2008, genetic diversity was very low; effective founders was 9.8 and effective ancestors only 5. |

Another statistic called "founder genome equivalents" (Ng) accounts for the random losses of alleles from the founder genomes by genetic drift over the generations since founding. The value of 2.1 for Ng of this population means that only the equivalent of 2.1 original founder genomes are still represented in the current population.

The ratio of fe/f (effective founders / actual founders) reflects the loss of original genetic diversity in the founders due to selection. If no genetic diversity has been lost, then fe and f would be equal.

The ratio of fa/fe accounts for bottlenecks that reduced genetic diversity. If fa is the same as fe, there has been no loss of genetic diversity as a result of bottlenecks.

The ratio of Ng/fe reflects the fraction of diversity lost from the founders that was a consequence of genetic drift.

The average level of inbreeding (COI) and the average mean kinship of the current population are both 26%. This indicates that on average the entire population of animals is as closely related as full siblings.

The effective population size (Ne), estimated from the rate of inbreeding, was 27.

Current genetic status of the breed

All of these statistics reflect substantial loss of genetic diversity from the breed over the generations since founding.

We can summarize all of this information like this:

1) The entire breed descends from about 20 founder dogs

2) The database of the breed contains more than 28,600 dogs (through 2010)

3) There was a surge in popularity beginning in the 1980s

4) Over the course of the breed's history, only a small fraction of the available dogs produced offspring

5) Inbreeding increased rapidly after 1960 and has remained higher than 25%

6) The effective population size of the current population is only 27 dogs

7) The population in 2010 had the genetic diversity of only 2.1 dogs (and it can only go down)

8) On average, the animals in the breed are more closely related than full siblings

This has been the result of a number of factors:

1) Low number of (related) founders

2) Low percentage of dogs used for breeding

3) Unbalanced use of males and females in breeding

4) Inbreeding that increased homozygosity in offspring

5) Popular sires

6) Historical genetic bottlenecks

7) Genetic drift

By any measure, this breed should be considered endangered.

--------------------

If you found this interesting, have a look at an analysis for the Icelandic Sheepdog as well as a much more comprehensive genetic analysis of pedigree data for the Afghan Hound.

The ratio of fe/f (effective founders / actual founders) reflects the loss of original genetic diversity in the founders due to selection. If no genetic diversity has been lost, then fe and f would be equal.

The ratio of fa/fe accounts for bottlenecks that reduced genetic diversity. If fa is the same as fe, there has been no loss of genetic diversity as a result of bottlenecks.

The ratio of Ng/fe reflects the fraction of diversity lost from the founders that was a consequence of genetic drift.

The average level of inbreeding (COI) and the average mean kinship of the current population are both 26%. This indicates that on average the entire population of animals is as closely related as full siblings.

The effective population size (Ne), estimated from the rate of inbreeding, was 27.

Current genetic status of the breed

All of these statistics reflect substantial loss of genetic diversity from the breed over the generations since founding.

We can summarize all of this information like this:

1) The entire breed descends from about 20 founder dogs

2) The database of the breed contains more than 28,600 dogs (through 2010)

3) There was a surge in popularity beginning in the 1980s

4) Over the course of the breed's history, only a small fraction of the available dogs produced offspring

5) Inbreeding increased rapidly after 1960 and has remained higher than 25%

6) The effective population size of the current population is only 27 dogs

7) The population in 2010 had the genetic diversity of only 2.1 dogs (and it can only go down)

8) On average, the animals in the breed are more closely related than full siblings

This has been the result of a number of factors:

1) Low number of (related) founders

2) Low percentage of dogs used for breeding

3) Unbalanced use of males and females in breeding

4) Inbreeding that increased homozygosity in offspring

5) Popular sires

6) Historical genetic bottlenecks

7) Genetic drift

By any measure, this breed should be considered endangered.

--------------------

If you found this interesting, have a look at an analysis for the Icelandic Sheepdog as well as a much more comprehensive genetic analysis of pedigree data for the Afghan Hound.

REFERENCE

Maki, K 2010 Population structure and genetic diversity of worldwide Nova Scotia Duck Tolling Retriever and Lancashire Heeler dog populations. Journal of Animal Breeding and Genetics; doi:10.1111/j.1439-0388.2010.00851.x

You can learn more about the genetic management of dog breeds in

ICB's Online Course

Managing Genetics for the Future

Next class starts

5 July 2021

Join us!