| You can learn more about hip and elbow dysplasia in ICB's online course "Understanding Hip & Elbow Dysplasia", which covers the most up-to-date information about causes, treatment, and prevention. Learn more HERE. |

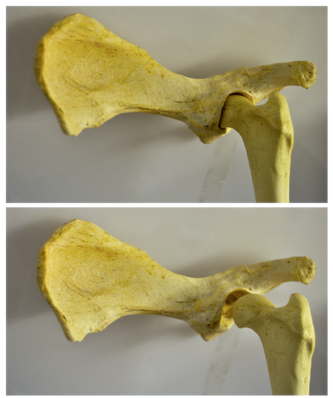

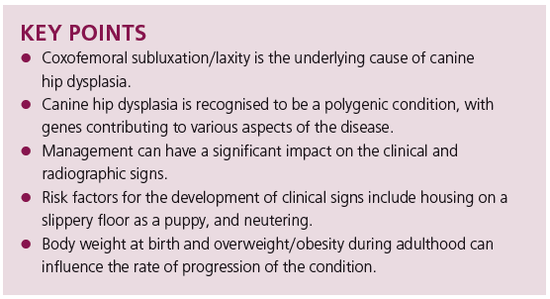

Witte PG, 2019. Hip dysplasia - understanding the disease. Companion Animal 24:77-81.

ICB's online courses

***************************************

Visit our Facebook Groups

ICB Institute of Canine Biology

...the latest canine news and research

ICB Breeding for the Future

...the science of animal breeding