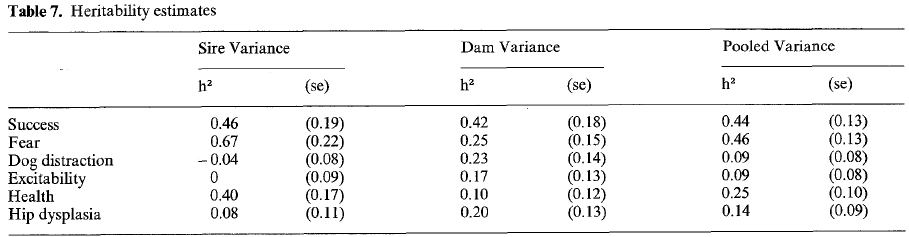

Heritability has a very specific meaning in genetics. The heritability of a trait is the fraction of the total variation in the trait among the animals in a population that can be accounted for by genetics. The variation that is not a consequence of genetic differences among individuals is lumped into the "non-genetic" category, which is called "environment". Values of heritability go from 0 to 1. If a trait is genetic but there is no variability in the population, the heritability is zero. If all of the variation from one individual to the next can be explained by differences in genetics, the heritability is 1; that is, 100% of the variation in the trait is accounted for by genetics. A trait that has no genetic influence, like hair color in a group of teens with neon spray-on paint, is not heritable.

| Since heritability reflects the relative influence of the genes that a dog has for a particular trait, it tells you how successful you're likely to be in improving a trait through selection. If heritability is high, then dogs with the preferred phenotype are likely to have the preferred genes. If heritability is low, the phenotype of the animal is significantly influenced by non-genetic factors, and the "best" animal by phenotype might not be the one with the "best" genes. As a familiar example, hip dysplasia has a low heritability, which means that the phenotype (assessed from an X-ray) is not an especially good predictor of the hips that will be produced in a litter of puppies, so it's not surprising that hip dysplasia continues to be a significant problem despite many generations of selection. |

The problem with the low heritability of behavioral traits in dogs is that behavior is usually evaluated very carefully when making breeding decisions - and the evaluator usually feels that they are making a useful assessment - yet all the studies and mounds of data generated over the last 50 years indicate that these assessments are very poor predictors of the genetic breeding value of the dog, as you will see.

This is well known among organizations that breed dogs for specific purposes, such as the military and guide dog organizations. A dog must meet certain standards of performance and behavior to be acceptable for work, and it is expensive and time-consuming to breed, raise, train, and evaluate a dog. Being able to identify at a young age the dogs that are most likely to make the grade is of huge importance, so the challenge becomes one of figuring out what can be assessed or measured in a puppy or young dog that will reflect its future behavior and performance. Just as important is the selection of animals to be bred, in which case you are hoping to choose the animals that are best suited genetically and therefore likely to pass their genetic value on to their offspring.

ASSESSING PUPPIES

- Wilsson E & P-E Sundgren. 1998. Behaviour test for eight-week old puppies - heritabilities of tested behavior traits and its correspondence to later behaviour. App. Anim. Behav. Sci. 58: 151-162.

- Riemer S, C Muller, Z Viranyi, L Huber, & F Range. 2014. The predictive value of early behavioural assessments in pet dogs- a longitudinal study from neonates to adults. PLOS One 9(7): e101237.

How useful are those tests that evaluate temperament in puppies? With a quick Google search, you can come up with a bunch of examples, and many people swear by these. But it is really difficult to prove that they are useful.

The goal, of course, is to determine some traits in the puppy that will predict behavior and performance as an adult, but the tricky thing is that the tests you would use on a puppy aren't appropriate for an adult and vice versa. So right from the start, you know you are evaluating things that are "proxy traits" - that is, you expect them to tell you something useful about some entirely different behavior when the animal is older.

The two papers noted above are worth reading. The first one convincingly showed that evaluations of puppies were of little use in predicting behavior as an adult. They evaluated 630 German Shepherds at 8 weeks and again at 450-600 days (roughly 1.5-2 yrs). They found that heritability of some of the behavioral traits they looked at was modest, so selection for those would result in some improvement. But the "correspondence of puppy test results to performance at adult age was negligible and the puppy test was therefore not found useful in predicting adult suitability for service dog work".

The second study is recent so the information is up to date, and it does a good job of recognizing the potential pitfalls of studying puppies to predict adult behavior. But again, they "found little correspondence between individuals' behaviour in the neonate, puppy and adult test. Exploratory activity was the only behaviour that was significantly correlated between the puppy and the adult test. We conclude that the predictive validity of early tests for predicting specific behavioural traits in adult pet dogs in limited".

An especially interesting outcome in this study is in the evaluation of fearfulness, which is the most common behavioral reason for a puppy to be rejected from a guide dog training program. They found that in evaluating fearfulness, "...some major changes were observed over time, with the initially most fearful individuals becoming most friendly to people or vice versa". That statement should give you pause. Could eliminating a puppy from a breeding program because of fearfulness be culling the dogs that will have the best temperaments as adults?

People that have been breeding dogs for decades and have much experience working with puppies might feel that they have some skill at evaluating temperament and behavior, but the studies that have tried to confirm the value of these evaluations have uniformly failed to validate them. Mind you, these studies used hundreds or even thousands of puppies from dozens of litters; the testing conditions were uniform, the protocols carefully followed, and the data analyzed with appropriate statistics. In the absence of properly done studies that demonstrate otherwise, there is no evidence that puppy evaluations have any value at all.

So what about the breeders of guide dogs? Do they do temperament testing on young puppies? Analysis of over 10 years of data from one guide dog center showed that selecting breeding stock on the basis of puppy tests did improve the performance of puppies on the tests, but did not improve the success rate of dogs finishing the program (Scott & Bielfelt 1976; Goddard & Beilharz 1986). Consequently, they wait to evaluate the suitability of dogs for further training until they are older.

EVALUATING DOGS BEFORE TRAINING

- Duffy DL & JA Serpell 2012 Predictive validity of a method for evaluating temperament in young guide and service dogs. App. Anim. Behav. Sci. 138: 99-109.

Since assessments of very young puppies are not very predictive of adult behavior, at what age should they be assessed? This study tested a group of dogs at 6 and 12 months of age, before they entered their training period to become a guide dog. They noted which dogs were successful in graduating from the program and looked for associations with any of the measured traits. The test they used (which was developed by one of the authors, Serpell) was the C-BARQ, which has been widely used for behavioral assessment of dogs. Note that they combined data from 5 different guide and service dog breeding programs, so they had a huge sample size - nearly 8,000 dogs. These were not anecdotal observations!

They found that dogs that successfully completed the guide dog training program "scored more favorably on 27 out of 36 C-BARQ traits at both 6 and 12 months of age compared to those that were released from the programs". Although they didn't find a trait that was very useful for predicting success, they were able to do a better job of rejecting dogs that were likely to be unsuccessful. In particular, owner-directed aggression was a very sensitive indicator of failing the program, and this at least is useful; eliminating dogs that are not likely to succeed spares the time and expense of training a dog that will ultimately wash out of the program. The other (rather unlikely) trait most predictive of failure in the guide dog program was "pulls excessively hard on a leash".

This study concluded that the C-BARQ test was useful in identifying the dogs that were least likely to succeed, but it was not a reliable indication of which dogs were most likely to be successful.

ASSESSING DIFFERENCES BETWEEN BREEDS AFTER TRAINING

- Ennik I, A-E Liinamo, E Leighton, & J van Arendonk. 2006. Suitability for field service in 4 breeds of guide dogs. J Vet. Behav. 1:67-74.

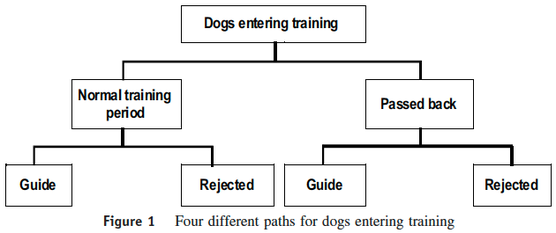

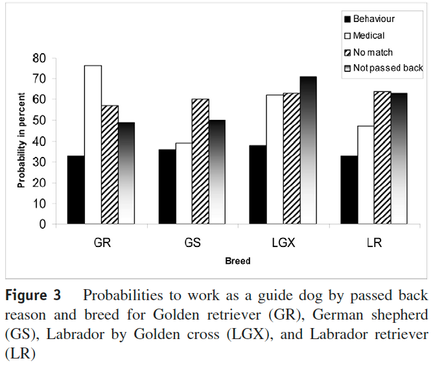

This study looked at the success rates of these three breeds and the Golden x Labrador cross in becoming guide dogs, and it also looked for effects of sex and whether a dog received additional training (was "passed back") because there was no suitable match with a person when it finished training, there was a temporary medical issue, or it wasn't progressing adequately.

REASONS FOR FAILURE

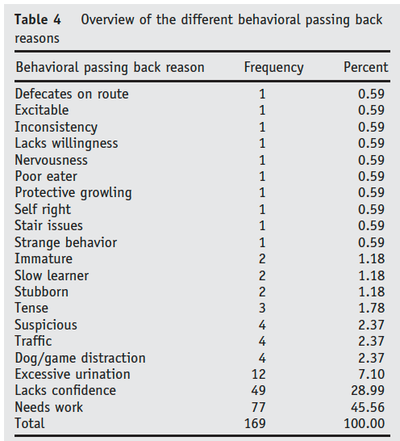

The most common behavioral reasons for failing out of a guide dog training program are fearfulness, dog distraction, and excitability. Although the heritabilities of dog distraction and excitability are low and can differ between males and females, the heritability of fear is relatively high (0.46 over both males and females; Goddard & Beilharz 1982).

From these studies (and many more like them), we can conclude that evaluating behavior in dogs and using that information for selective breeding has proven to be extremely difficult, even in well-managed breeding programs in which the dogs are bred and raised under controlled conditions, receive similar treatment and experiences, and are assessed by trained handlers.

If we believe in genetics (which of course we do!), we would expect that dogs from selective breeding programs should have low rates of behavior problems, but still 70% of the dogs that fail to complete the program are removed because of behavior. Perhaps a better way to judge whether these specialized breeding programs are successful is to note that in the early days when dogs for guide dog training programs were donated by the public, the success rate was 9%; selective breeding improved the success rate to 90% in just a few generations (Pfaffenberger 1963). It is the remarkable early success of the guide dog breeding programs that provided the convincing evidence that broad differences in behavior among breeds are heritable, and that improvement within breeds is possible.

WHAT ABOUT TEMPERAMENT TESTING PUPPIES?

There are two very important messages to take away from this.

1) Be very skeptical of claims that temperament can be assessed through evaluation of young puppies. If there is somebody who can reliably do this, they should document their success in a publication, because it would revolutionize the breeding of dogs. Otherwise, the best way to predict the temperament and behavior of a dog as an adult is to assess it as an adult.

2) Nobody wants to produce puppies that will grow up to have behavior problems, but in breeds where low genetic diversity and small population sizes are resulting in high rates of genetic disorders and low fertility, excluding dogs from breeding based on evaluation of behavior, especially as puppies, should be done very carefully. Aggression and fearfulness have reasonable heritabilities and can be selected against if evaluated as adults, but for most other traits heritability is very low and therefore evaluations of behavior don't tell you much about a dog's genetic value for these traits.

One final point. The efficiency of selection can be improved by estimating breeding values statistically using information about not just the dog of interest but about parents, siblings, and progeny (i.e, estimated breeding values, EBV). The guide dog organizations have been using EBVs to select for the traits of interest to them (both behavioral and physical) for a couple of decades with good success (Leighton 2003), and the technique should be similarly useful to dog breeders if they are willing to collect the appropriate data to set up the program.

If you have a dog, you can do your own C-BARQ assessment from their website at the University of Pennsylvania vet school:

http://vetapps.vet.upenn.edu/cbarq/

Ennik I, A-E Liinamo, E Leighton, & J van Arendonk. 2006. Suitability for field service in 4 breeds of guide dogs. J Vet. Behav. 1:67-74.

Goddard ME and RG Beilharz. 1982. Genetic and environmental factors affecting the suitability of dogs as guide dogs for the blind. Theor. Appl. Genet. 62: 97-102.

Goddard ME and RG Beilharz. 1986. Early prediction of adult behaviour in potential guide dogs. App. Anim. Behav. Sci. 15: 247-260.

Leighton, EA. 2003. How to use estimated breeding values to genetically improve dog guides. Presented at a meeting of the "Original Group", September 11-12, 2003.

Pfaffenberger C. 1963. The new knowledge of dog behavior.

Riemer S, C Muller, Z Viranyi, L Huber, & F Range. 2014. The predictive value of early behavioural assessments in pet dogs- a longitudinal study from neonates to adults. PLOS One 9(7): e101237.

Scott JP & SW Bielfelt. 1976. Analysis of the puppy testing program. Pp. 39-76, in CJ Pfaffenberger, JP Scott, JL Fuller, BE Ginsburg, and SW Bielfelt (Eds). Guide dogs for the blind: their selection, development and training.

Wilsson E & P-E Sundgren. 1998. Behaviour test for eight-week old puppies- heritabilities of tested behaviour traits and its correspondence to later behaviour. Appl Anim. Behav. Sci. 58: 151-162.

You can learn more about the genetics of dogs in ICB's online courses.

******************************

Visit our Facebook Groups

ICB Institute of Canine Biology

...the latest canine news and research

ICB Breeding for the Future

...the science of animal breeding