Why was estimating relatedness important? Back in the day, breeders understood the general effects of parental relatedness on quality of offspring. They knew that a bit of inbreeding increased the uniformity, predictability, and quality of many traits in offspring. But they also found that too much inbreeding had negative effects, a phenomenon called "inbreeding depression." Starting with a population of outbred animals, Wright summarized the dual consequences of inbreeding here (Wright 1922):

| "First, [there is] a decline in all elements of vigor, as weight, fertility, vitality, etc., and second, an increase in uniformity within the inbred stock, correlated with which is an increase in prepotency in outside crosses... The best explanation of the decrease in vigor is dependent on the view that Mendelian factors unfavorable to vigor in any respect are more frequently recessive than dominant, a situation which is the logical consequence of the two propositions that mutations are more likely to injure than improve the complex adjustments within an organzism and that injurious dominant mutations will be relatively promptly weeded out, leaving the recessive ones to accumulate, especially if they happen to be linked with favorable dominant factors. On this view, it may be readily shown that the decrease in vigor in starting inbreeding in a previously random-bred stock should be directly proportional to the increase in the percentage of homozygosity... As for the other effects of inbreeding, fixation of characters and increased prepotency, these are of course in direct proportion to the percentage of homozygosis. Thus, if we can calculate the percentage of homozygosis which would follow on the average from a given system of mating, we can at once form the most natural coefficient of inbreeding.” |

| Wright is saying that deleterious mutations that are dominant will show their effects and can be weeded out, but recessive mutations that have no effect unless homozygous will tend to accumulate in the genome over time. Consequently, crossing related animals runs the risk of producing offspring that are homozygous for previously silent recessive mutations, with deleterious consequences that can range from an obvious functional defect to subtle changes in health, vitality, longevity, and so on. Therefore, breeders in Wright's time wanted to be able to figure out the level of inbreeding so they could balance the benefits with the risks when striving to producce the best quality animals. Wright realized that because both the positive and negative effects come from alleles on individual loci, changes in the fraction of loci that are homozygous would have a direct and proportional effect on the traits that are improved as well as those that are detrimental. This allowed breeders to identify the "sweet spot" in COI where their animals would have the highest value because of the best tradeoff between benefit and detriment. |

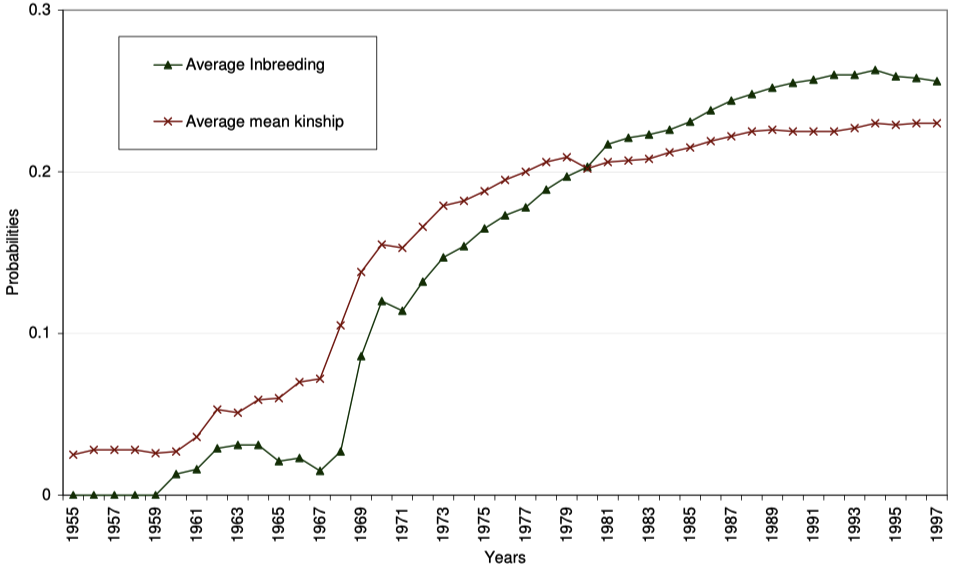

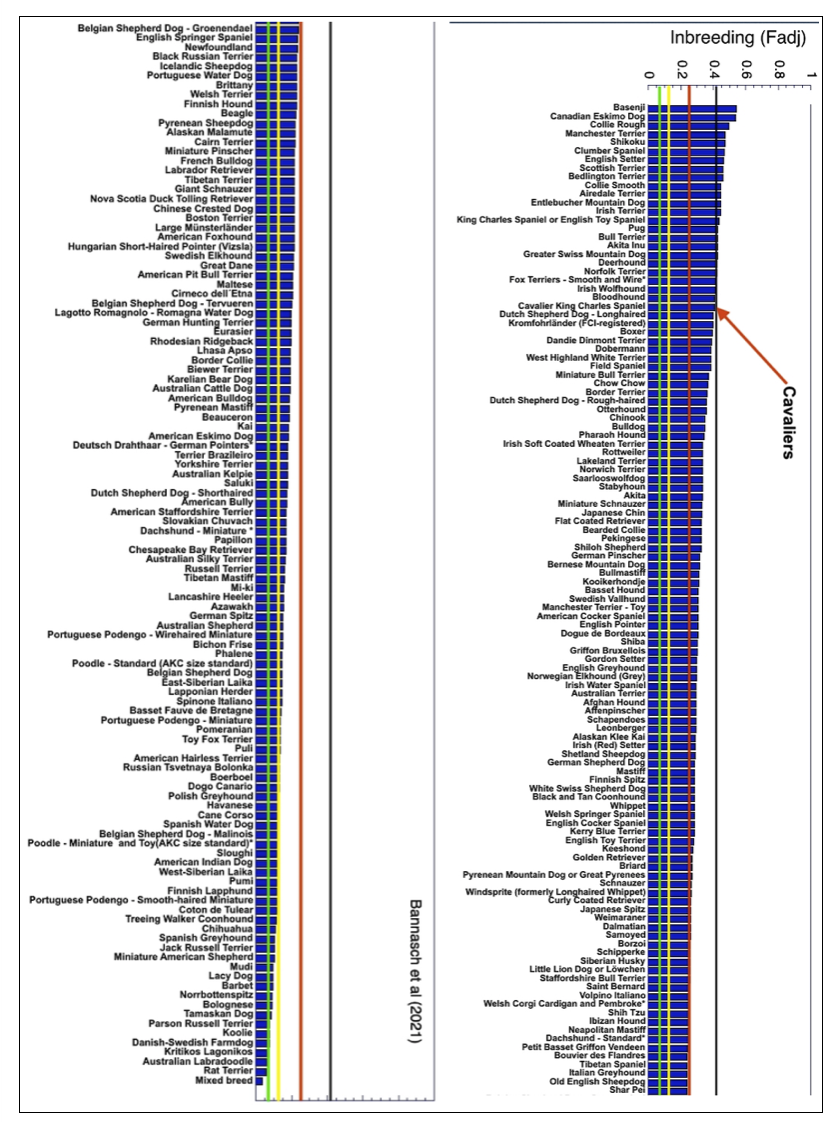

Oliehoek also used a related statistic, the kinship coefficient, to reveal how breeding strategy in the population had changed over time. The kinship coefficient measures the degree of relatedness (in terms of genetic similarity) between two individuals. The kinship coefficient is also equal to the inbreeding coefficient of offspring produced by a pair of animals. In other words, the inbreeding coefficient of an animal is the kinship coefficient of its parents. When Oliehoek plotted both the inbreeding coefficient (black symbols and line on the graph below) and kinship coefficient (red symbols and line) on the same graph as probabilities (i.e., values between 0 and 1.0), he showed that in the early history of the breed, there was preferential avoidance inbreeding that is revealed because average inbreeding was less than average kinship in the population (the black line is lower than the red line); that is, breeders chose to pair individuals that were less closely related than average in the population. This was the case until the early 1980s, when these lines flipped, with the average inbreeding increasing faster than average kinship, reflecting a preference by breeders for closer inbreeding, even when pairs were available that would produce lower levels of inbreeding.

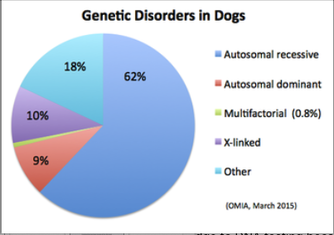

| We can see that the coefficient of inbreeding and the related statistic, the kinship coefficient, can be valuable tools in providing breeders with information that can be used for breeding decisions as well as population management. But the inbreeding coefficient has another, extremely useful role to play, this one in the prevention of genetic disorders and inbreeding depression. The inbreeding coefficient quantifies the probability of an animal inheriting two copies of the same allele from a shared ancestor. This is also the fraction of all loci that are expected to be homozygous. We can put this information to use to reduce the risk of genetic disorders in offspring. We know that most genetic disorders in dogs are caused by autosomal recessive mutations, with estimates ranging from about 60% to 80%. So, for these health issues, the risk of producing a problem in a puppy is equal to the probability of that puppy inheriting two copies of the same mutation, which is exactly what the coefficient of inbreeding tells us. So, if the inbreeding coefficient is 25%, the equivalent of a pairing of littermates, the risk of producing a genetic disorder caused by a recessive mutation is also 25%. Similarly, if the COI is 40%, there is a 40% chance of a puppy inheriting two copies of the same mutation. Likewise, a COI of 10% puts the risk of producing a genetic disorder from a recessive mutation at 10%. When recessive mutations account for such a large fraction of all genetic disorders in dogs, the benefits of being able to reduce or even prevent them is very significant. Note that this also means that if the inbreeding coefficient predicted is much below 25%, there would be little benefit from doing DNA tests. |

| Remember that there is another deleterious effect of inbreeding apart from causing genetic disease from recessive mutations, and that is inbreeding depression, which is a general decline in the traits for "fitness" - things like lifespan, fertility, and what breeders used to call "vigor" or "vitality". These are not caused by a mutation per se, but by the loss of advantageous alleles or combinations of alleles at particular loci. For instance, there is something called "heterozygote advantage", in which the heterozygous genotype is more beneficial than either homozygous state (i.e., Aa is better than either AA or aa). You lose these beneficial allele combinations when inbreeding, and even though the effects can be are subtle, they can impact the quality of life of the animal in important ways. |

REFERENCES

Oliehoek, PA, P Bijma, & A van der Meijden. 2009. History and structure of the closed pedigreed population of Icelandic Sheepdogs. (pdf)

Wright S, 1922. Coefficients of inbreeding and relationship. Am Nat 56: 330-338. (pdf)

ICB's online courses

***************************************

Visit our Facebook Groups

ICB Institute of Canine Biology

...the latest canine news and research

ICB Breeding for the Future

...the science of animal breeding