A recent study has accumulated data for about 100,000 dogs, including about 83,000 mixed breed dogs and 18,000 purebred dogs representing 330 breeds (Donner et al 2018). For testing, the authors used a SNP array that tests for 152 known mutations, or "variants," at the same time. These tests cannot identify all mutations, only the ones that have been identified and localized at a particular SNP. So the data represent only a fraction of the actual number of mutations in the entire gene pool.

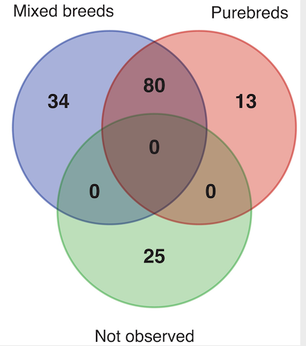

The data reveal that 34 mutations were only seen in mixed breed dogs, 13 were only seen in purebreds, and 25 were not found in this sample population. Of the mutations identified, 80 were found in both mixed and purebred dogs. If we add up the numbers for mixed and purebreds, we find that a total of 114 mutations (34 + 80) were found in mixed breed dogs, and 93 occurred in purebred dogs.

You might look at these data and conclude that this is proof that purebred dogs are healthier than mixed breeds. Would you be correct?

One consequence of this behavior of recessive mutations is that a dog can be a carrier of many mutations but suffer no ill effects from any of them. In fact, because of this, recessive mutations can be passed from parent to offspring generation after generation without affecting the health of the dog.

Dogs that inherit two copies of a mutation (called homozygous, affected, or "at risk") are likely to display some negative effects like blindness, exercise collapse, a nervous disorder, or some other disturbance to a body function. If the consequences are severe enough, natural selection or the breeder will remove the dog from the population of breeding animals and those mutations are not passed on to offspring.

So we have two situations: in one, a dog carries a single copy of the mutation and suffers no ill effects (heterozygous), and in the other the dog carries two copies and the mutation is expressed as a genetic disorder.

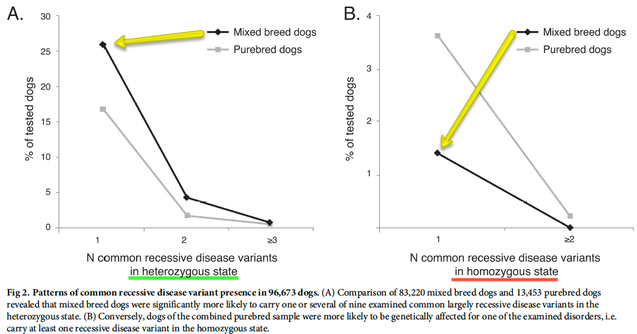

This pair of graphs show the proportions of mixed breed and purebred dogs in which the mutations were heterozygous (left). The graph on the right shows the proportion of dogs in which the mutations were homozygous (right). Mutations in the heterozygous state on the left were found in both mixed and purebred dogs, but as we would expect from the Venn diagram above, more of the mixed breed dogs were carrying mutations (yellow arrow). The graph on the right shows what we really need to see: both mixed and purebred dogs had homozygous mutations, but they were much higher in purebred than mixed breed dogs.

Here is what the study's authors had to say:

| "The distribution of the number of disease variants carried in the heterozygous state differed significantly between mixed breed dogs and the combined purebred sample, with a higher ratio of mixed breed dogs being carriers of the common analyzed disease risk alleles.... However, when we compared the groups for the number of common recessive disease variants carried in the homozygous state, an opposite pattern emerged... Purebred dogs were 2.7 times more likely than mixed breed dogs to be genetically affected for at least one of the common recessive disorders (3.9% vs. 1.4% of dogs, respectively)." |

In a nutshell, here's what they found:

a) The collective population of mixed breed dogs contains more recessive mutations than that of purebreds, but those mutations are more likely to be heterozygous and therefore harmless.

b) On the other hand, there are fewer mutations found in purebred dogs, but they are far more likely to be homozygous, and therefore expressed as a genetic disorder, than in mixed breed dogs.

It is this simple property of recessive mutations, of only being expressed when homozygous, that results in the higher rate of genetic disorders in purebred than mixed breed dogs.

This comparison of the health of mixed and purebred dogs is oft debated, and breeders usually argue that purebred dogs are just as healthy as mixed breed dogs. For problems caused by non-genetic disorders (broken bones, allergies, and the like), this could be true. But, for genetic disorders, the purebred dogs fare far worse than mixed breed dogs. It's a simple matter of the genetics of recessive mutations.

Why are there more mutations hanging around in the huge gene pool of mixed breed dogs? It's because recessive mutations are harmless if they are heterozygous, so they are not eliminated from the population by selection. The frequency of a specific mutations in the population is usually very low (< 1%, with a few notable exceptions, like the mutation associated with degenerative myelopathy, DM). The chances of any two random mixed breed dogs having the same mutations is low. Although a mixed breed dog can be affected by a genetic disorder caused by a recessive mutation if it inherits two copies, the chance of this happening is very low.

Breeding purebred dogs in a closed population means that all of the dogs in a breed are related and therefore share many genes in common. Some of these shared genes will be mutations. The more closely related the sire and dam, the more likely the puppies are to be afflicted with a genetic disorder caused by a recessive mutation.

This is why the best strategy for reducing the incidence of genetic disorders in purebred dogs is not endless DNA testing. To control the risk from all mutations, the ones you know about as well as the ones you don't, the best strategy is to reduce the relatedness of the parents. Reducing genetic disease in dogs boils down to reducing the risk of a puppy inheriting two copies of the same recessive mutation. The way to accomplish this is to reduce the relatedness of the parents.

Donner J, H Anderson, S Davison, AM Hughes, and others. 2018. Frequency and distribution of 152 genetic disease variants in over 100,000 mixed breed and purebred dogs. PLOS Genetics 14(4):31007361. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1007361

Check out ICB's course "COI Bootcamp"

*** Visit our Facebook pages ***

ICB Institute of Canine Biology

...the latest canine news and research

ICB Breeding for the Future

...the science of animal breeding