Let's have a look the results of a breeding program that did a cross that most would think is crazy, of a Boxer to a Pembroke Corgi.

| When it became clear that tail docking was likely to be banned in the UK, Dr Bruce Cattanach, a boxer breeder and geneticist, undertook an experiment to see if he could produce Boxers with naturally bobbed tails. He knew that the bobbed tail in the Pembroke Corgi was the result of a single dominant gene, which meant that it should be possible to do a breed cross that would produce Boxers with naturally bobbed tails. The Corgi's longer coat and short legs were inherited as dominants, so it would be easy to remove puppies carrying those genes after the first cross. Cattanach wasn't worried about the fact that the Corgi was so different in structure to the Boxer. In fact, he said that "In the series of backcrosses planned, it should not matter what I started with. Unwanted characteristics of whatever nature would all be diluted out, generation by generation." |

| "Nevertheless, quite apart from these two genes, I was hugely surprised at just how easy it was to get back to Boxer appearance by repeated crossing to Boxer after the initial Corgi cross." |

The Boxer x Corgi Crossbreeding

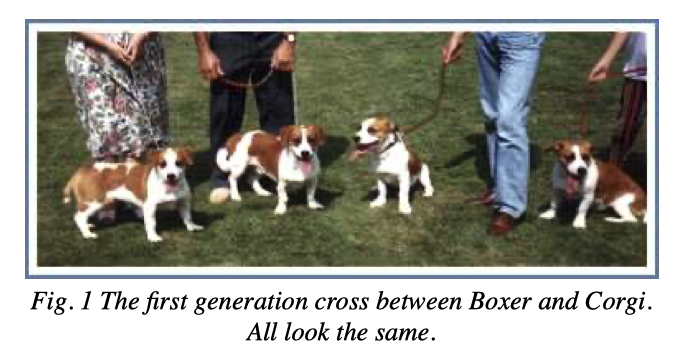

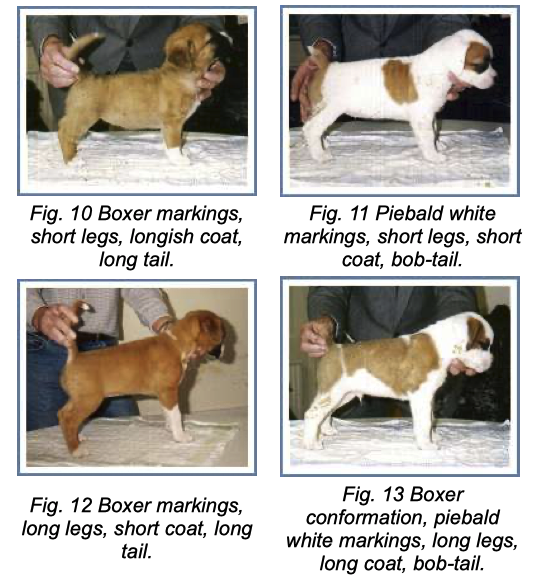

| "A first prediction from crossing of two breeds (Fig. 1) is that, barring the segregation of individual genes in each breed, eg red versus brindle, all the progeny should look alike. But, what else could be expected? 1. Corgis have a fawn colour with the same genetic basis as Boxers, but they differ with regard to several known genes; 2. the white markings are caused by a different form of the gene responsible for whites and white markings in Boxers; 3. the legs are short (dominant); 4. the coat is long relative to that of the Boxer (supposedly dominant); 5. the ears are erect (supposedly recessive); 6. Corgis do not have the black masking factor (dominant); and finally, 7. the Corgi used in the cross had a single dose of the bob-tail gene (dominant). The Corgi-Boxer crossbreds were therefore expected not only to be uniform in appearance; they should be fawn, have intermediate near-50:50 levels of white markings (piebald), perhaps show a black mask (dependent upon white markings), have short legs, a longish coat, and drop ears, but the bob-tail gene was expected to segregate such that only half the puppies would have bob-tails. Beyond this, the unique head features of the Boxer might be expected to give way to the more normal Corgi head." |

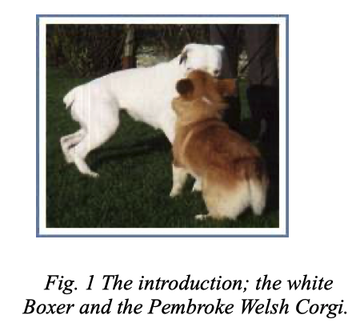

Cattanach bred a white Boxer named Polly to a Pembroke Corgi with a natural bobbed tail. They produced a litter of seven puppies that all looked alike, with a fawn color and piebald white markings, and traces of a black mask on some. Five had bobbed tails of various lengths and two had normal tails. In structural traits, the Corgi influence predominated. The legs were short and coats longish, reflecting the influence of those dominant genes. The head resembled that of the Corgi, but with drop ears ( at 7 months the ears of one pup were erect) and eyes more like those of a Boxer. These pups were dubbed the "Borgies" and apparently were unbearably cute.

The F1 Hybrid x Boxer Backcross

| "As both the crossbred dams and Boxer sire were fawn, all the pups were expected to be likewise, and all should have dominant black mask of the Boxer. However, all the main Corgi-Boxer differences (leg length, coat length, ear carriage) as well as tail type should separate out among the offspring. Moreover, because the Boxer sire, Foreign Service, carries the gene for white and the crossbreds carry both the Boxer and Corgi forms of the gene, further complexity regarding white markings was anticipated. It is perhaps best to present the expected outcomes in terms of the odds of their occurrence: 1. To take the project into the next generation, and also for practical and economic reasons, it was necessary to keep a bitch. Therefore, from the 16 puppies obtained in the backcross, only 8 on average might be expected to be bitches. 2. Any bitch to be of use for further breeding must, of course, have a bob-tail. Therefore, with a dominant inheritance, it could be expected that only half the pups would inherit the gene from their crossbred dams. Thus, of the possible 8 bitches, perhaps only 4 could be expected to have bob-tails. 3. Because of all the difficulties in mating short and long legged dogs, I desperately wanted any bob-tail bitch which I was lucky enough to get to have long legs. Again, only half of the possible 4 of interest might have this characteristic; maybe 2 out the original 16! 4. Then there was the coat length; only half again. Therefore, if I wanted to the short coat too, there would be only 1 chance in 16 of getting the combination wanted, a bitch with bob-tail, long legs and short coat. And this is without the white markings problem. Adding this: a. one-quarter of the pups were expected to be white, with the risk of deafness that this would entail; b. one-quarter were expected to show the piebald level of white marking like the crossbred dams; c. one-quarter were expected to have flashy white markings like the sire; and, d. one-quarter were expected to be near-solid, but carry the gene for the Corgi type of white markings. |

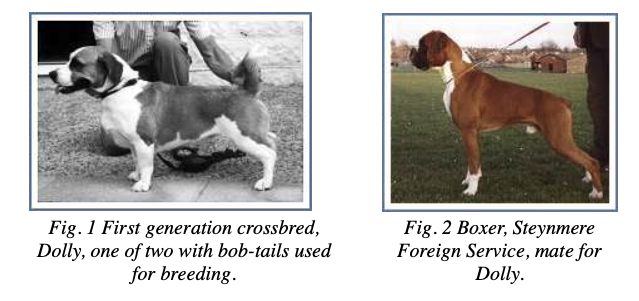

Two of the female hybrid pups, Dolly and Tess, were chosen to be backcrossed to one of Cattanach's male Boxers. They produced 9 and 7 puppies respectively. These varied from Boxer-like to "Borgi", with legs of varying length and about half with bobbed tails (7 of 16).

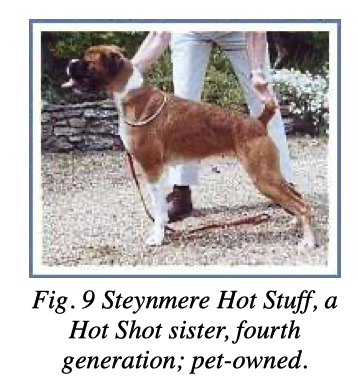

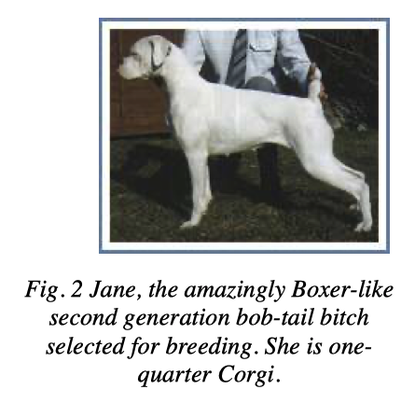

| "In all, the base colour was fawn with black mask. The white markings were of the four expected types. Two pups were white, 4 were of the piebald type, 8 were flashy and 2 were near-solid. However, what stunned us most was that some of the pups looked like pure bred Boxers of pick of litter quality (Fig.9)." |

| "The surprising discovery at this stage was that few genes seem to distinguish two such diverse breeds as the Boxer and Corgi. Apart from those concerned with head properties, these specifically include those for leg and coat length. The presence of finer points that distinguish the Boxer from other breeds could still be said to be variably evident however. Thus, so far as even the most Boxer-like dogs from the first backcross were concerned, there still seemed to be something foreign about them. In the case of Jane, further development of head was required, she needed a larger eye, stronger and harder musculation, a shorter, harder coat and more bone. So, further improvements were needed, but perhaps little more than those involved in the ordinary task of trying to breed good show animals. Fortuitously, because of the dominant inheritance of the main unwanted characteristics (short legs and long coat), there was no need to worry about these appearing in Jane's descendants. She had the long legs and a short coat and therefore did not carry the short leg and long coat genes, and so could not transmit them. All that needed to be done was to breed selectively over a further generation or two of backcrossing the bob-tail gene into the Boxer to create a bob-tailed but otherwise typical "Boxer". And, this might be achieved in a single further generation, with a judicious choice of sire and a little bit of luck." |

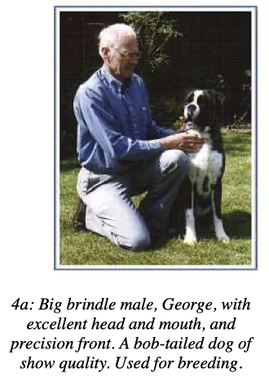

The Second Backcross

| "1. all the pups should be coloured and have flashy white markings within the recognised Boxer range. There would be no whites, solids or piebalds; 2. half the litter should be brindle like the sire and half should be red/fawn, Chief being a carrier of red and Jane being a red/fawn "under" the white, as indicated by her two tiny spots of red/fawn coat; 3. half the litter should inherit the bob-tail gene from Jane and be bob-tails, while the rest would have normal length tails; 4. all the pups should look like Boxers, with no "throwbacks" to the dominant Corgi characteristics (short legs, long coat); and, 5. head types, hopefully, would be much improved and, barring any total surprises, these should fall within the range exhibited by the parents." |

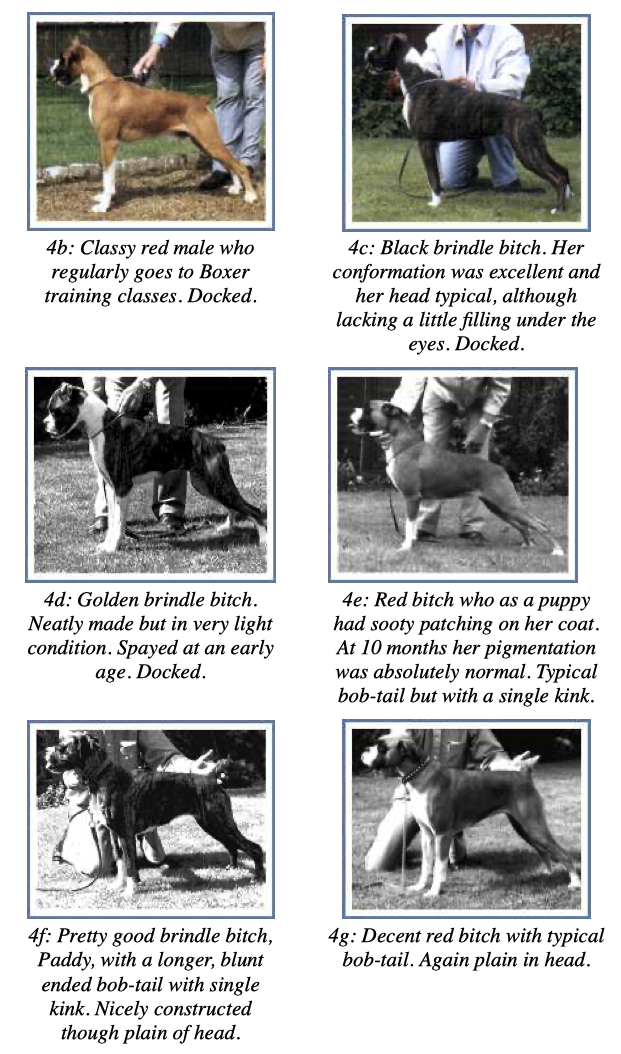

| "Boxer type prevails (Figs 19 & 20 above). All have long straight legs, short backs and short coats. There is nothing foreign in their build to suggest Corgi in their ancestry...Heads, however, betray them, but only when considered as a litter. Some have Boxer heads of a standard that at this age one would be pleased to have in any Boxer litter. Thus, two have extremely short deep heads that surely derive from the Continental Boxer background, while a third has a finer skull, yet with great muzzle development and with a really beautiful eye (Fig. 21). Only one in fact has a longer head somewhat pointy muzzle that has some suggestion of Corgi. The heads of the remaining three puppies fall between the two extremes but, despite some inadequacy of stop, this would never identify them as other than purebred Boxers...Beyond this, all of the puppies have the undershot jaw, which will not alter, and several have extraordinary, wide, straight mouths which are better than commonly seen in Boxer pups. Maybe this will stay. And eye size looks very good...Of more importance is the development of the bob-tails. Here, I have to express a little disappointment. While two pups have acceptable short tails like their dam, with just a dip at the end attributable to soft tissue and hair, which could be trimmed, the other two each have a definite tail kink (Fig. 23). Despite this additional feature, I think it can still be fairly claimed that one of the original objectives has just about been achieved. We now have several 'bob-tail Boxers' of potential show quality. Time will decide whether the latter is really true." |

These are the seven pups from the second backcross litter at 10 months. Four of these inherited bob tails; the rest were docked.

The Third Backcross

At the end of the project, Cattanach provided the details of all of the breedings to the UK Kennel Club with a request to consider them for registration. The KC agreed to register the fourth generation as Boxers and the previous ones as crossbreds.

Descendants of Cattanach's bobtail Boxer breeding experiment can be seen in the European show ring today.

The "catastophe" of the Corgi x Boxer cossbreeding project

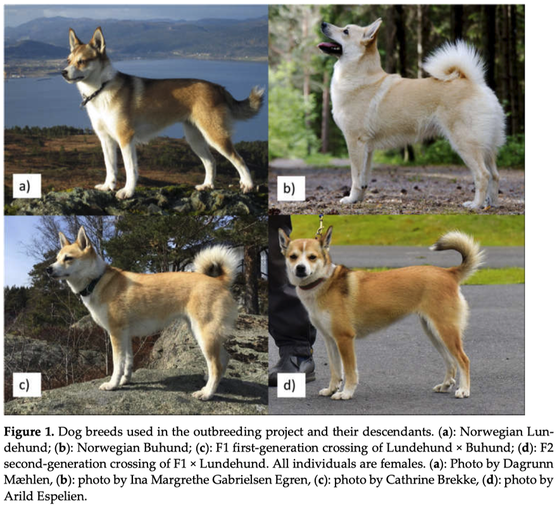

The Corgi x Boxer cross produces puppies that are 50% Corgi and 50% Boxer genes (inheriting one chromosome from each parent), the "Borgies". The gene for short legs is dominant, so they are all short. In the first backcross, the puppies will pick up more Boxer alleles, averaging 75% Boxer and 25% Corgi. Depending on which alleles each pup inherits from each parent, the traits in these puppies can vary widely, some looking much like Boxers. Among these was Jane, a white bitch with very good Boxer type that Cattanach used for the next backcross. As expected, if the best of the pups from the first backcross is crossed again to a Boxer, there should be much uniformity among the pups because now they carry on average 87.5% Boxer alleles and only 12.5% from their Corgi ancestor. These dogs looked like Boxers.

This is not the catastrophic genetic mish-mash many breeders fear will be the result of a cross-breeding. With some basic knowledge of a few key genes, Cattanach was able to predict what each cross would produce. This allowed him to get quickly from initial breed cross to producing entire litters of dogs of that are unmistakably Boxers, with no hint of their cross-bred ancestry, and some even of show quality.

Cattanach was interested in transferring only a single gene, and his breeding strategy was centered on that. He was able to make progress quickly in this project because he knew that the traits that made the Corgi look so different from the Boxer would be easy to select away from. A breeder would use a different breeding strategy if the goal was to improve genetic diversity, but the same principles would apply.

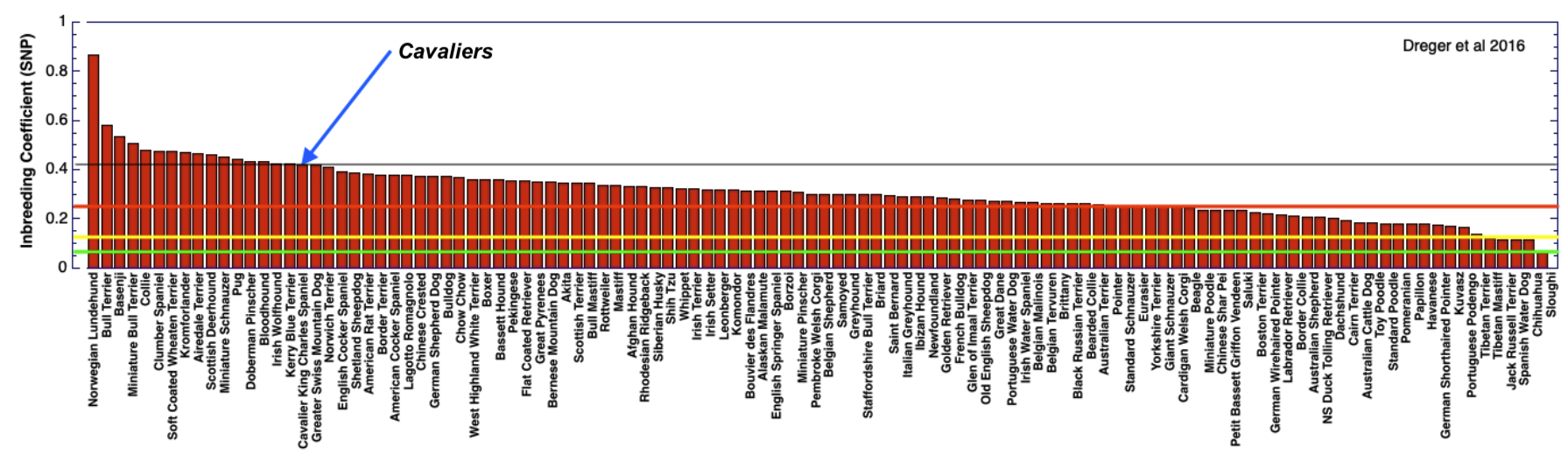

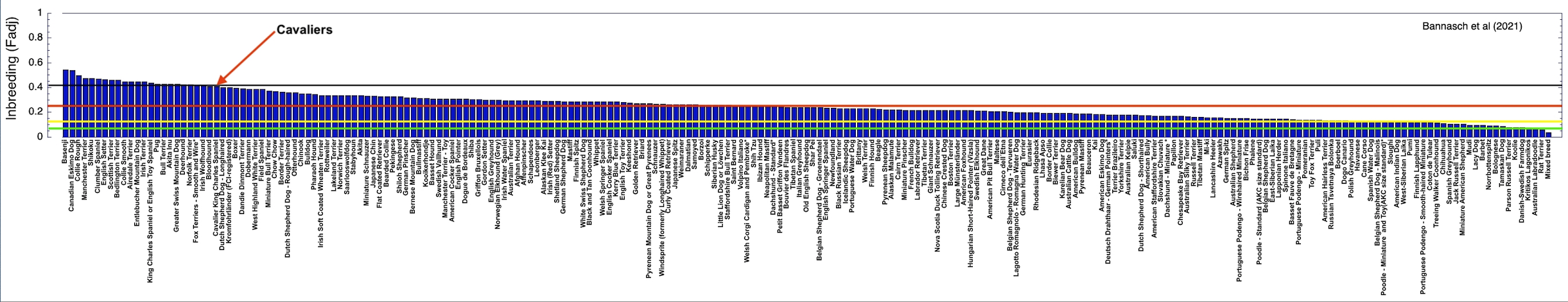

If your breed has high inbreeding (okay, Sloughi, you're good; this is for the rest of you), crossbreeding can restore the genetic diversity that has been lost over the generations. Let go of fear and believe in genetics.

What about registering the puppies? Cattanach was able to register his by request. These days, the kennel clubs are under the gun to improve health "or else" (see the court case in Norway). Because there is no other way to do this than crossbreeding in most breeds, I expect there will be little resistance to registering puppies that descend from crossbreeding programs in the future.

There are a few other examples of crossbreeding programs in dogs that I will be summarizing as well. I will post links here when those are available.

ICB's online courses

***************************************

Visit our Facebook Groups

ICB Institute of Canine Biology

...the latest canine news and research

ICB Breeding for the Future

...the science of animal breeding