At the root of most health issues in dog breeds are the small size of the gene pool and high levels of inbreeding. Let me explain why these things are a problem.

| The Cavalier King Charles Spaniel was founded on only a handful of dogs. I've seen numbers of 6 and 8; let's just call it a handful. If the stud book is closed, then all the genes the breed will ever have come from those few dogs. Also, because the stud book is closed, dogs can only breed to related dogs. There are no "outcrosses" here; every dog is closely related to every other dog. It's a bit like trapping you and your immediate family on an island from which there is no escape. You can only breed with kin. Over time, the animals in a closed population can ONLY become more closely related (genetically similar) to each other. Inbreeding can ONLY increase. Furthermore, gene variants are lost every generation through selective breeding and also just by chance. So the variation in the genes in those original 8 dogs is gradually lost over time. Eventually closed populations like this have such high levels of inbreeding that they are wrecked by health problems and infertility, and they simply go extinct. |

For half-sib pairings, the inbreeding produced in the offspring is higher, averaging 12%. Full-sib pairings produce offspring with inbreeding of 25%. For a recessive mutation in the genome, that is a 25% risk of producing an affected animal.

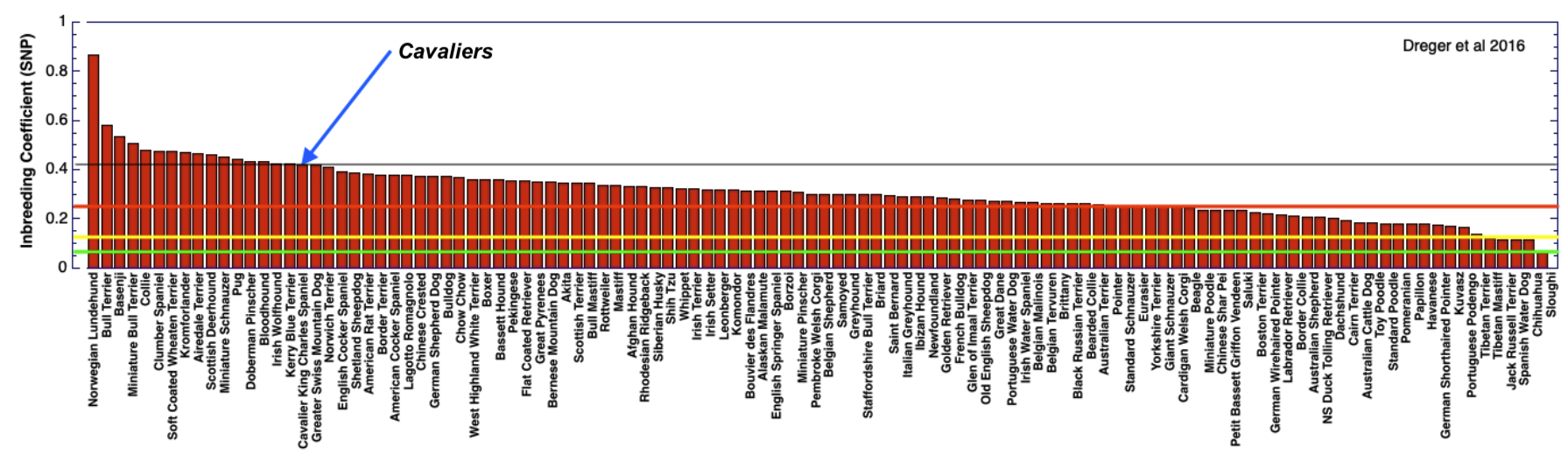

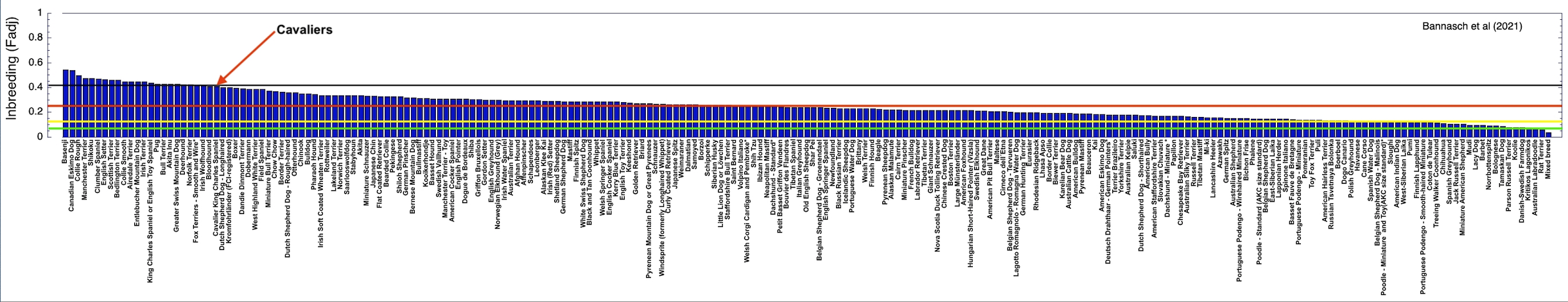

The problem with Cavaliers is that their level of inbreeding is extraordinarily high. We said that a full sibling cross resulted in inbreeding of 25%. Have a look at these two graphs.

I rounded up the data for two studies, one that included 10 dogs per breed based on US (mostly AKC registered) dogs Dreger et al (2016), and another that included data for 455 Cavaliers registered with the FCI, AKC, UKC, or the Kennel Club ( Bannasch et al., 2021).

For the Dreger et al. dataset (the red graph below), the inbreeding based on DNA for the Cavalier averaged 42.1% (black line), and for the Bannasch et al. data, inbreeding averaged 41.1%. For two unrelated datasets, of very different sizes, the level of inbreeding in the Cavaliers was essentially the same. This reflects the high level of inbreeding and genetic similarity among the dogs. It really doesn't matter how you sample the population, the estimate of average inbreeding doesn't vary much.

The black lines on the graphs are at the average level of inbreeding in Cavaliers in those two studies. (I have included links below to download the jpg file so you can blow it up big enough to read the breed lavels.) Remember, 25% inbreeding results from a full sibling cross from unrelated parents. The level of inbreeding in Cavaliers is way - WAY - higher than that. Most people would not do a breeding of two littermates, but the inbreeding data show that in fact most breedings are between dogs much more closely related (i.e., genetically similar) than littermates.

We do DNA testing to identify carriers of mutations so we can avoid the 25% risk of producing a puppy that is homozygous for the mutation. We know that every animal has many mutations lurking in its genome, and we can't test for the ones we don't know about. But the probability of producing a puppy homozygous for an unknown mutation is going to be the same as from a known one.

Cavaliers are all so closely related to each other that the average inbreeding produced in a puppy is 40% so the risk of homozogysity in a mutation is 40% as well.

Now, think about this.

You do your DNA testing to avoid producing a puppy affected by a known mutation, which you can prevent entirely by not mating two carriers.

But for all those unknown mutations in the genome, the risk of producing an affected puppy is the same as the average inbreeding, which is actually 40%, not 25%.

DNA testing allows us to test for carriers of mutations so that we can avoid this 25% risk of producing affected animals. But when all the dogs in the population are closely related, the average inbreeding of a litter is 40%, far above the 25% risk you're trying to avoid. You can see from this that health testing in Cavaliers is really not accomplishing anything except costing you money.

The problem with science is that it's true even when it's not what you would like to believe. The data for Cavaliers are clear. No amount of selective breeding is going to improve the health of this breed. You might temporarily reduce the incidence of some specific nasty mutation temporarily in a part of the population, but everybody is in the same genetic pot. Inbreeding will continue to go up over time, the small genetic differences between populations will disappear over time as genetic diversity declines, and eventually you will no longer be able to produce healthy animals. In fact, this is where Cavaliers appear to be now.

Cavaliers are in deep trouble. There are plenty of other breeds in similar shape, but what matters to those that love Cavaliers is whether it can be saved. We know that we can only restore health by restoring genetic diversity. We do know how to do with without losing breed type. Animal breeders have been doing this for hundreds of years to produce quality animals that can be nearly identical, with inbreeding levels in the single digits. It can just as easily be done for dogs as well, and Cavaliers are a perfect candidate. But not in a closed gene pool.

I have to say that what I have read on social media this week makes me worry that breeders will continue to argue about the arrangement of the deck chairs while the ship slowly slips under the waves. I hope I'm wrong.

Dreger, DL et al, 2016. Whole-genome sequence, SNP chips and pedigree structure: building demographic profiles in domestic dog breeds to optimize genetic-trait mapping. Disease Models & Mechanisms 9(12): 1445-1460. https://doi.org/10.1242/dmm.027037

Bannasch E et al 2021. The effect of inbreeding, body size and morphology on health in dog breeds. Canine Medicine and Genetics 8:12. doi.org/10.1186/s40575-021-00111-4

| dreger_et_al_2016_f_cavaliers.png |

| bannasch_et_al_2021_cavaiers_fadj.png |

ICB's online courses

***************************************

Visit our Facebook Groups

ICB Institute of Canine Biology

...the latest canine news and research

ICB Breeding for the Future

...the science of animal breeding