With the availability of affordable DNA analysis that can provide information about hundreds of thousands - or even millions - of markers, we have started to look for the genetic basis of behavior at the level of the gene. A few genes have been identified that are associated with specific behavioral traits in dogs, like xxxxxxxx (Bridgett). There is also a growing number of studies that looked for the genetic basis of behavioral differences in dog. But as I explained in an earlier post, the associations of behavior with genes have been generally weak and not especially useful for identifying genes of major effect or improving traits through genomic selection.

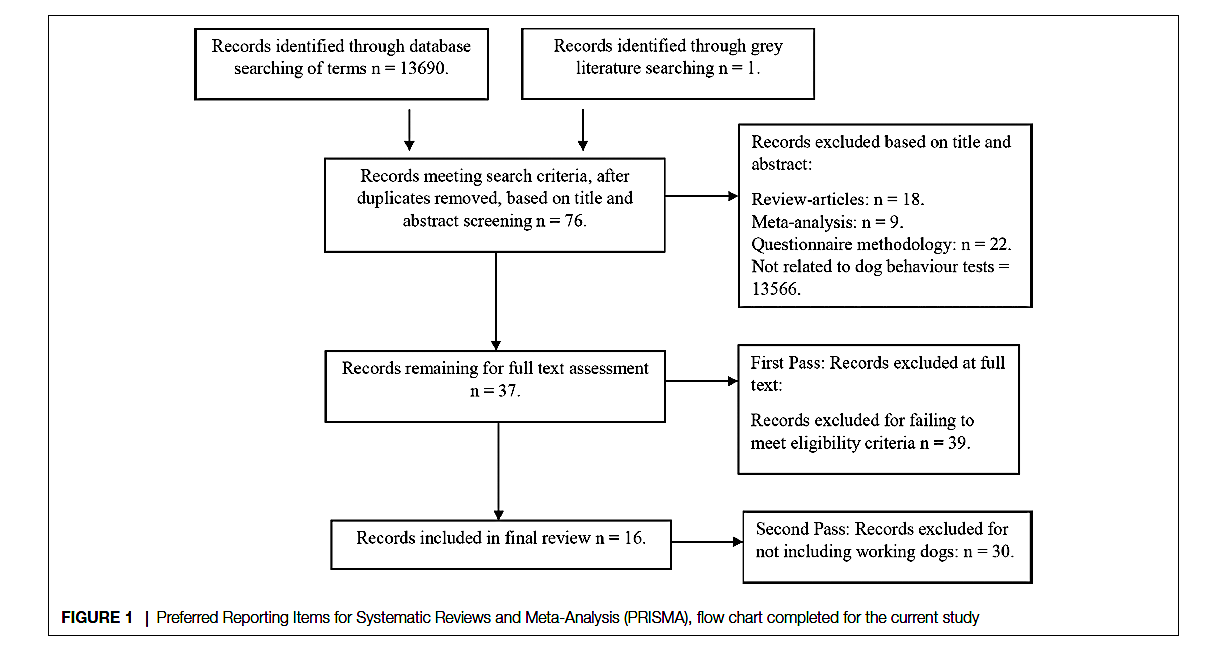

A new study, however, is a game-changer (MacLean et al 2019). It has been made available before submission for publication, so it has not been subject to peer review and you should keep that in mind. But what it offers is a tantalizing first look at links between genes and behavior in dogs.

Instead of focusing on a particular breed, the new study looked for major differences in behavior and genetics across many breeds. And here, they were successful.

What they found was fascinating.

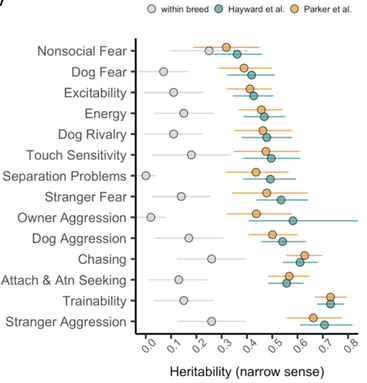

In this graph, the behaviors they looked at are indicated down the y-axis, and the strength of the association between genetics and the trait, i.e., heritability, is on the x-axis. The stronger the association, the higher the heritability. The grey dogs are measurements of heritability made on dogs of the same breed. The green and yellow dogs display heritability of those same traits when the associations are made looking across breeds.

You can see here that heritabilities determined from dogs of the same breed are generally low, less than about 0.3, which means that 30% or less of the variations in behavior can be attributed to variations in genotype.

But when you compare across breeds, the average heritabilities are high, from about 0.4 (40% of variation explained) to more than 0.7 (70% of variation explained.

This is a game-changer. Our understanding of the genetic basis of behavior in dogs has gone molecular.

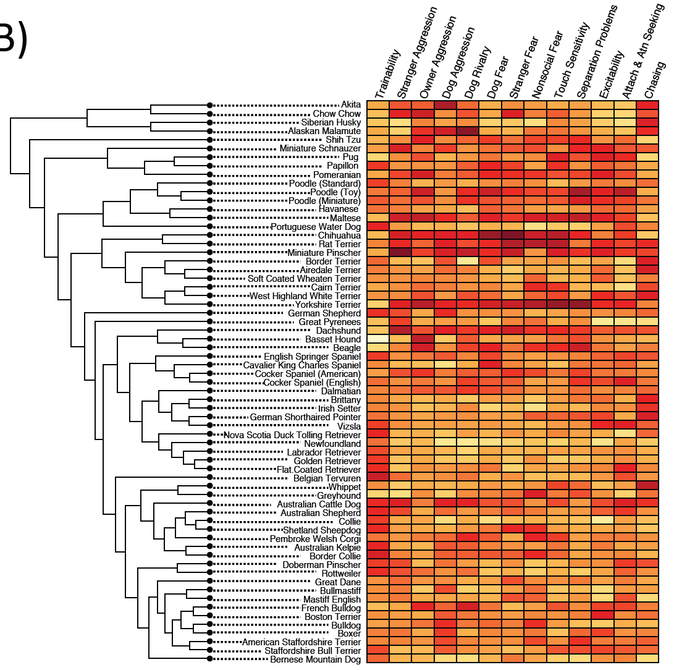

We now have large databases for both behavior and genotype, and these will continue to grow in size because the methodology for both is standardized (CBARQ for behavior and high-density SNP for genotype). These allow us to do analyses like the one below, which is a "heat map" that depicts the behavioral scores by breed displayed along with the dendrogram displaying their genetic relatedness. You can easily find the sporting dogs because they are high in trainability, and the small breeds like the chihuahua, rat terrier, and miniature pinscher stand out for scoring high in traits that we might describe as reactive or "fiesty" (e.g., aggression, fear). The herding breeds score high in trainability while the hounds are low. And now we are finally able to explore the genetic basis for major breed-specific differences in behavioral traits among dog breeds.

This paper will need to go through peer review, revision if necessary, then publication, so don't expect to see the final version for at least a few months. But I suspect we're about to see a flood of studies that also leverage the large datasets now available for both behavior and genetics. Buckle up!

NOTE: If you are interested in the links between genetics and behavior, now is the time to start boning up on the jargon and concepts you need to understand these studies. You can find relevant articles in the blog posts on the ICB website (just search for a topic or keyword). Even better, ICB has courses designed for dog people with no background in science that will get you up to speed. This genie is out of the bottle. A little homework now to learn the basics will pay off every time you read about an exciting new paper about the genetics of behavior in dogs!

People are drawing all sorts of conclusions about behavior of dog breeds from this paper. That's not what this paper is about.

Here it is in a nutshell:

| For 14 traits in dog breeds, in general h ^2 (heritability) = vg/(vp) = 0.4 to 0.7 where vp = vg + ve. What is so ground-breaking about the study is that the estimates of h ^2 across breeds are much greater than h ^2 determined within breeds. |

This is not a paper about behavior. It is about measuring something called heritability (h ^2). Here's the translation of that first equation:

Heritability is the fraction of the variation in a trait that can be attributed to variation in genetics.

This study shows that there is a measurable fraction of the variation in a number of behavioral traits in dogs that is due to genetics.

Heritability doesn't mean "inherited". It doesn't tell you how much variation there is in a trait. It doesn't tell you how likely a dog is to inherit a behavior. None of those things.

Clearly, to understand this paper, you need to be really clear on the meaning of heritability. You can start learning about it by reading some of my blogs on the ICB website, starting with this one:

Understanding the heritability of behavior in dogs

There are others if you do a search.

Also, please consider taking the Genetics of Behavior course. We will go through some papers like this one (including this one!) so you have a good understanding of what the information does - and doesn't - mean. There will be more studies like this one. Make sure you get the most out of them by understanding the science.

Check out those blog posts, and consider taking my course that starts (coincidentally) next week, 4 March 2019:

MacLean EL, N Snyder-Mackler, BM vonHoldt, & JA Serpell. (unpub) Highly heritable and functionally relevant breed differences in dog behavior. BioRxiv preprint accessed 27 February 2019.. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/509315.

ICB's online courses

***************************************

Visit our Facebook Groups

ICB Institute of Canine Biology

...the latest canine news and research

ICB Breeding for the Future

...the science of animal breeding