| NOTE: An earlier version of this post indicated that Balance It was affiliated with UC Davis. It is not. If I learned anything from my last post, it's that if you want to talk to dog people about what they feed their dogs, you had better be prepared to step in some poop. You would think the discussion would be largely about nutrition - things like protein content, mineral ratios, digestibility, minimum daily requirements, and those sorts of things. But no. The discussion is strongly ideological, with several camps that firmly believe that what they feed their dogs is the only right way and everyone else is wrong, and of course the commercial dog food companies are just plain evil. The religions are many: Prey Model Raw, BARF (which is a registered trademark!), Meat With Bone, the Ultimate Diet, the Volhard Diet, and others, and proponents of each vigorously debunk the claims of the others. Much of the discussion centers on whether dogs are carnivores (facultative? obligate?) or omnivores (with "carnivorous tendencies"?), and the arguments are largely based on personal perceptions of the biology of the wolf (many of which are incorrect) and opinions about the diets of dogs during domestication. |

"This article contains weasel words: vague phrasing that often accompanies biased or unverifiable information."

Yep, that about sums it up.

One meme that appeared in the discussions of my post that unfortunately included the word "diet" in the title was the oft-repeated notion that "we don't know much about ____ diet because nobody wants to pay for the research, least of all the commercial dog food companies." Well, in fact, there IS information about non-commercial diets for dogs if you take the time to look.

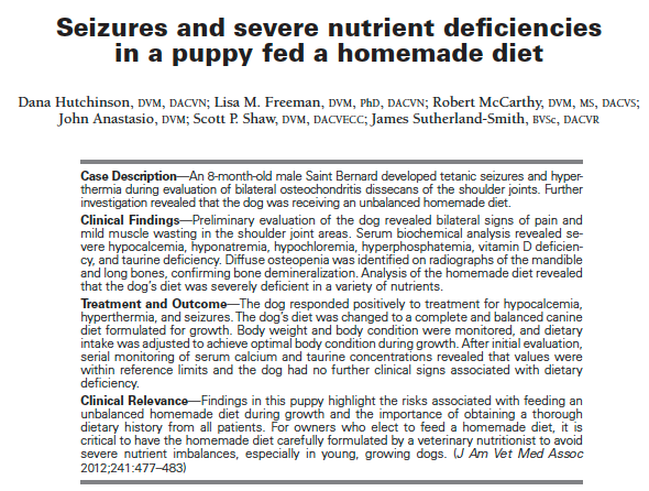

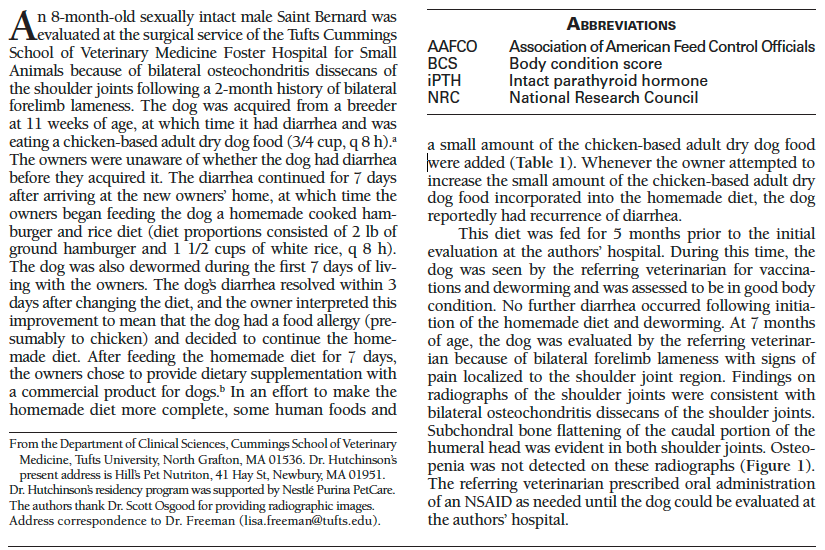

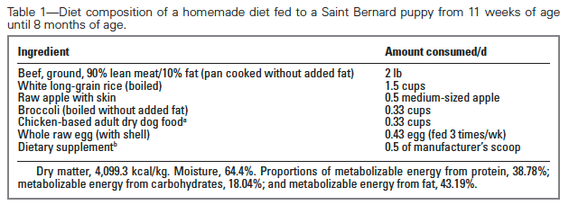

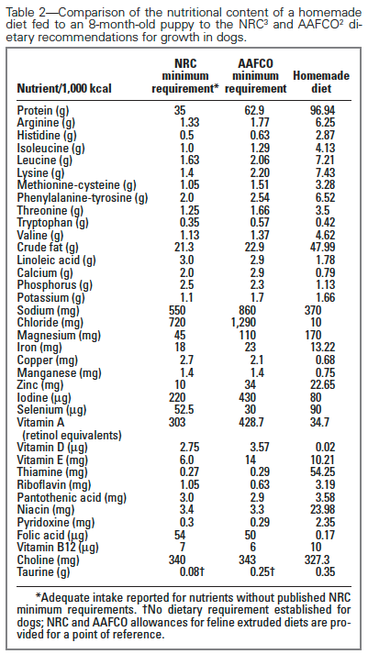

A 2013 study performed a nutritional evaluation of 200 homemade diets made from recipes published in books (including pet care books and veterinary textbooks), on the internet, and other sources. About 65% of these were written by veterinarians. Of these, only four (4!) were nutritionally complete, and those were designed by veterinary nutrition specialists.

"Most (184 [92%]) recipes contained vague or incomplete instructions that necessitated 1 or more assumptions

for the ingredients, method of preparation, or supplement-type products. Supplement-type products were not included in 58 (29%) recipes. Most (169 [84.5%]) recipes did not provide specific feeding instructions; instead, some included general instructions to modify amounts on the basis of each individual pet’s size and body weight (including any patterns of weight gain or loss). Similarly, most (171 [85.5%]) recipes did not provide calorie information or the target body weight for a pet. Additionally, some sources provided recipes that differed widely in calorie content for the same-size pet. Thirteen (6.5%) recipes included garlic or onion, which are foods associated with hemolytic anemia in dogs.

Many proponents of less structured recipes for home-prepared diets assert that although each day’s

meal is not necessarily complete, rotation and variety will provide a balanced diet overall. Our analysis indicated

that this assumption was unfounded because evaluation of 3 recipe groups, each of which comprised 7 separate recipes, did not eliminate deficiencies. In addition, many recipes had similar deficiencies, with 14

nutrients provided at inadequate concentrations in at least 50 recipes. Thus, even the use of a strategy for

rotation among several recipes from multiple sources would be unlikely to provide a balanced diet. A greater number of recipes written by nonveterinarians had deficiencies, those recipes had significantly (P = 0.001) more nutrients that were deficient, and the deficiencies were more severe, compared with results for recipes written by veterinarians (Table 2). The lower number of deficiencies per recipe in those written by veterinarians may have been associated with a better understanding of canine nutrition by veterinary professionals, although most of the veterinarian-written recipes had at least 1 nutrient deficiency. Only 4 recipes written by board-certified veterinary nutritionists were available for evaluation; all 4 had nutrient profiles that were within the AAFCO-recommended ranges for an adult canine maintenance diet." (Stockman et al 2013)

Note that the authors state that while 129 (65%) of the recipes they tested were written by veterinarians, only 4 were nutritionally complete. If the veterinarians aren't getting it right, it's clear that there is a need for better, more accessible information for both owners and their veterinarians.

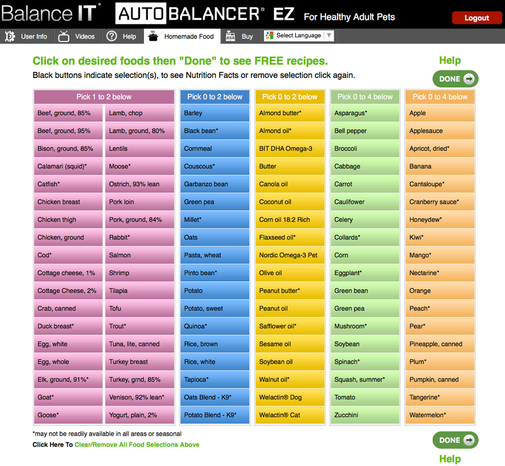

I don't know if those already wed to their diet philosophy will have any interest in doing some research about their diet, but for those trying to work through advice from friends, dodgy websites, magazine articles, and the many lay experts on Facebook, here are some great places to start.

WEST COAST USA

All Creatures Veterinary Nutrition Consulting, Dr. Stratton-Phelps in CA +1-707-429-2433

University of California, Davis +1-530-752-7892

EAST COAST USA

Tufts Cummings School of Veterinary Medicine +1-508-839-5395 ext. 84696

Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine +1-607 253-3060 or +1-203-595-2777

University of Pennsylvania Veterinary Medicine +1-215-746-8387

Oradell Animal Hospital, Dr. Laura Eirmann in NJ +1-201-262-0010

Red Bank Veterinary Hospital, Drs. Cline and Murphy in NJ +1-732-747-3636

VA-MD Regional College of Veterinary Medicine +1-540-231-4621

MIDWEST USA

The Ohio State University College of Vet Med Veterinary Medical Center +1-614-292-3551

University of Minnesota Veterinary Medical Center +1-612-626-8387

University of Missouri +1-573-882-7821

SOUTHERN USA

Veterinary Nutritional Consultations, Dr. Rebecca Remillard in NC +1-252-257-1959

University of Tennessee +1-865-974-8387

North Carolina State University College of Veterinary Medicine +1-919-513-6999

The University of Georgia College of Veterinary Medicine +1-706-542-5870

University of Florida College of Veterinary Medicine Small Animal Hospital +1-352-392-2235

CANADA

University of Guelph Ontario Veterinary College Teaching Hospital In-person appointments only +1-519-823-8830

AUSTRALASIA

Massey University Veterinary Teaching Hospital, Dr. Nick Cave in New Zealand +64 06 350 5329

GENERAL ACVN INFORMATION

Information about the American College of Veterinary Nutrition

EUROPE

Royal Veterinary College Queen Mother Hospital for Animals, Dr. Dan Chan in London +44 (0)1707 666366

Universiteit Utrecht +030 253 9411

VetsNow Referrals, Dr. Marge Chandler Email: [email protected], Phone: +44 (0)141 332 3212

Weeth Nutrition Services, Dr. Lisa Weeth Email: [email protected]

GENERAL ECVCN INFORMATION

When the new page loads, click on the "download the list of ECVCN Diplomates here" link

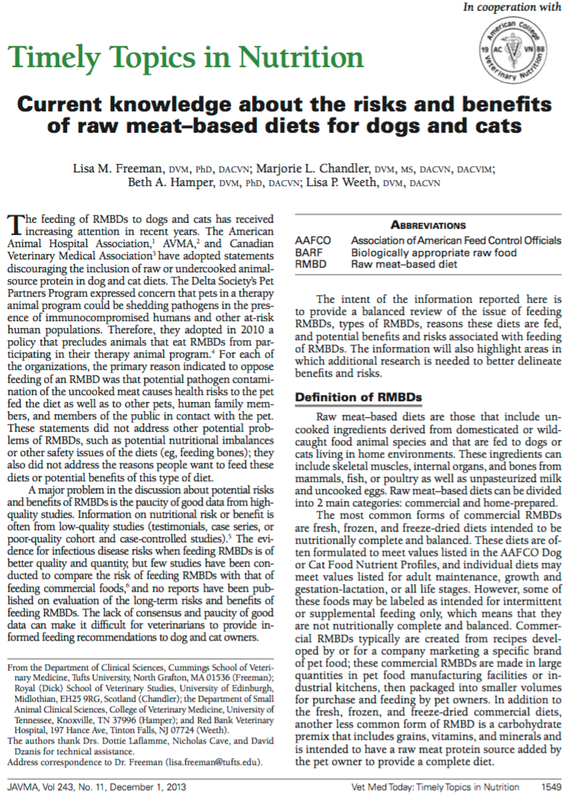

Freeman LM, ML Chandler, BA Hamper, & LP Weeth. 2013. Current knowledge about the risks and benefits of raw meat-based diets for dogs and cats. JAVMA 243: 1549-1558. (free download)

Stockman J, AJ Fascetti, PH Kass, JA Larsen. 2013. Evaluations of recipes of home-prepared maintenance diets for dogs. JAVMA 242: 1500-1505.

Check out

ICB's online courses

*******************

Coming up NEXT -

Managing Genetics for the Future

Starts 9 November 2015

Sign up now!

***************************************

Visit our Facebook Groups

ICB Institute of Canine Biology

...the latest canine news and research

ICB Breeding for the Future

...the science of dog breeding