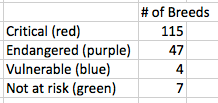

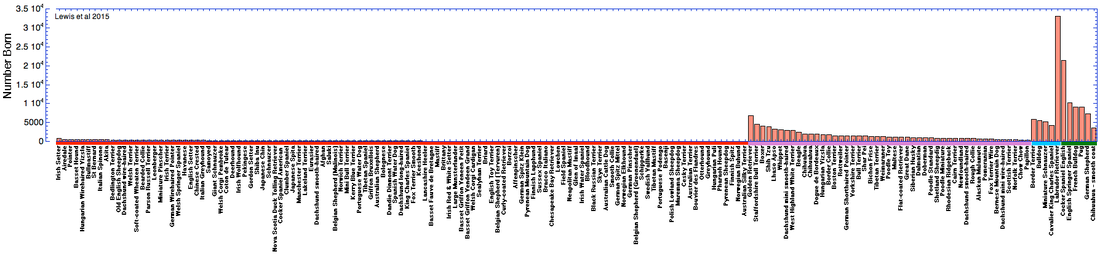

Of 173 breeds in the UK for which there are data, the status of 66% (115 breeds) is "critical", the FAO's highest risk category for domestic animal breeds. Another 27% (47 breeds) are "endangered", and 2% (4 breeds) are "vulnerable". Only 7 breeds (4%) could be classified as "not at risk". The reasons for the high proportion of breeds at risk are low numbers of breeding animals and an inadequate number of sires used for breeding. Comparable information is desperately needed for breed populations in other countries as well as the overall size and status of the global population.

The risk status of dog breeds in the UK

"The disappearing dogs: Ex-popular pedigrees face extinction as fashionable pets take over", announced one news source, and from the BBC it was "UK native dog breeds 'at risk of extinction'".

On the list were both well-known breeds like the English Setter, Bloodhound, and Mastiff, and less familiar breeds such as the Dandie Dinmont Terrier, Otterhound, and Skye Terrier. The most recent list includes 29 breeds described as "vulnerable" and another 11 that are "at watch".

The KC list was the result of an evaluation of the recent trends in population size, which for these and many other breeds in both the UK and elsewhere have been falling. They only evaluated the native breeds of England and Ireland, but the data are available to do similar assessments of other breed populations in the UK.

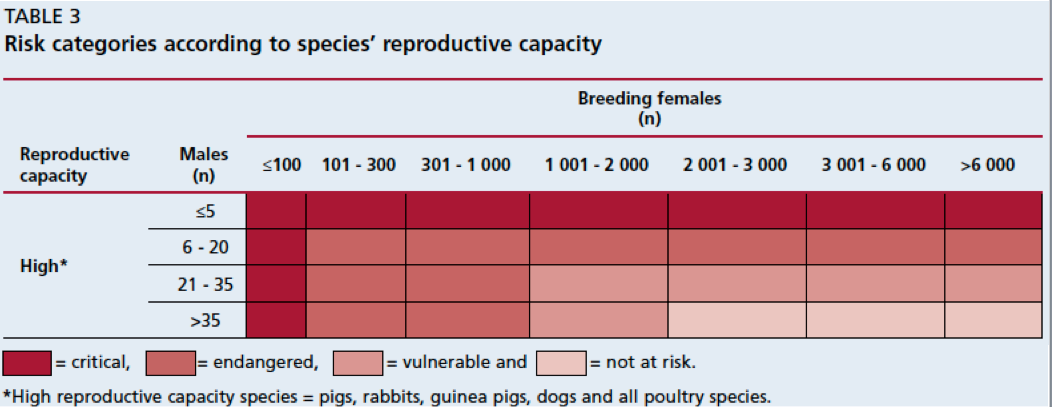

Lewis et al (2015) summarize information on population status, genetic diversity, and levels of inbreeding of more than 200 breeds in the UK based on the Kennel Club stud book records. This information can be used to assess vulnerability using some simple guidelines developed by the FAO for domestic mammals and birds.

This FAO table for risk assessment is designed to be used for species with "high reproductive capacity" such as rabbits, dogs, and poultry. It bases risk status of a population in a particular country on the number of breeding females and males, with 7 size categories for females (from less than 100 to greater than 6,000) and four for males (from less than 5 to more than 35).

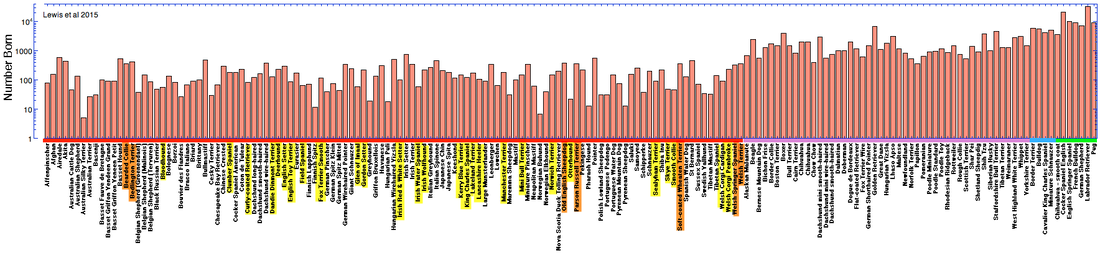

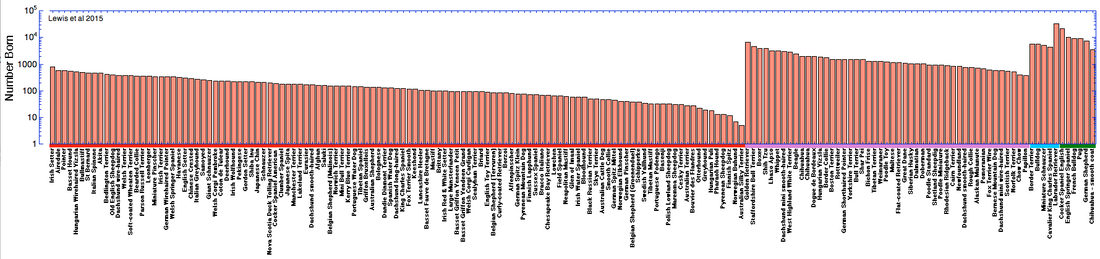

Of the 173 breeds for which I tabulated data, only seven were classed as "not at risk", and these included the six breeds with the highest number of offspring born in 2014 (English Cocker, English Springer, French Bulldog, German Shepherd, Labrador Retriever, and Pug) plus the Chihuahua. Four breeds were classed as "vulnerable" (Border Terrier, Bulldog, Cavalier King Charles Spaniel, and Miniature Schnauzer). Of the remaining breeds, 47 were designated as "endangered", and 115 as "critical".

I have also indicated the native breeds designated by the UK Kennel Club as either "vulnerable" (yellow highlight) or "at watch" (orange highlight). All of the latter fell within the "critical" risk group.

You can download a larger version of this graph here:

| uk_kc_status.png |

You can download larger copies of both of these graphs here:

| no_born_with_status_log.png |

| number_born_with_status.png |

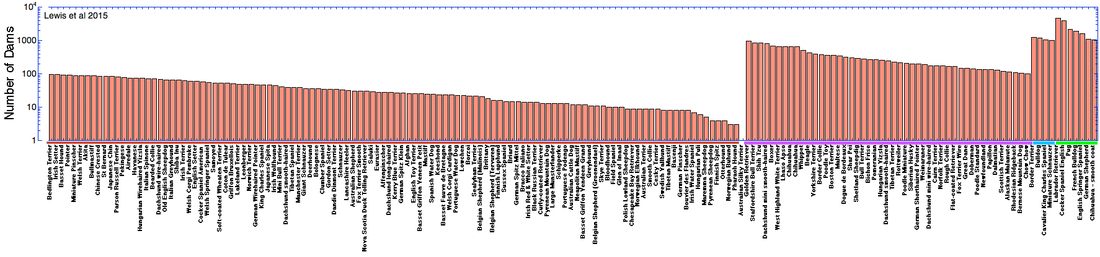

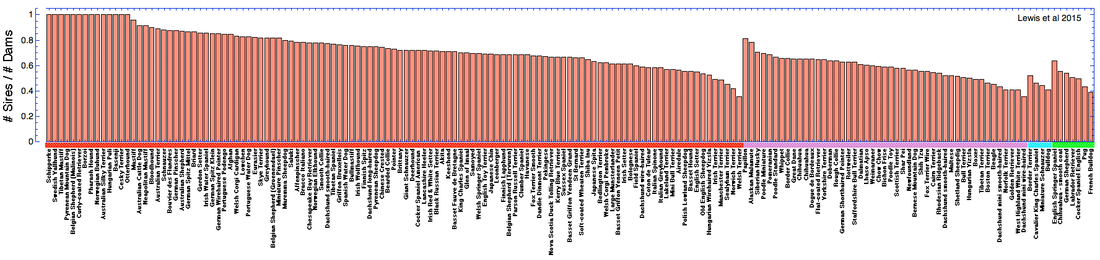

Here I have graphed the breeds by number of dams and also as the ratio of the number of sires to number of dams.

You can download larger versions of these graph here:

| _dams.png |

| sires_dams_status_rank.png |

How can we reduce the risk of a breed's extinction?

What is the most effective way for breeders to reduce the vulnerability of a breed? Small populations, regardless of the number of males, are at the highest risk of extinction. Increasing the number of breeding females to greater than 100 in a population that has at least 6 males will reduce risk from critical to endangered. To downgrade to "vulnerable" status, a population needs at least 1,000 dams and more than 20 sires; to be classed as "not at risk", the population must have > 2,000 dams and more than 35 sires. It will be difficult for all but the most popular breeds to achieve the status of "not at risk" using these criteria. Only the Pug, English Cocker Spaniel, and Labrador Retriever recorded more than 2000 dams in 2014.

For most of the breeds classed as "critical" in the UK, moving to "endangered" status will require at least doubling the number of females being bred; there are more than 40 breeds for which the number of breeding females is fewer than 20. For most breeds, it will be easier to increase the number of males used for breeding, and this is an important strategy in any case because it will increase the effective population size and reduce the rate of increase in the level of inbreeding.

The numbers of some breeds in the UK have skyrocketed in the last decade. These include multiple breeds in the Utility (non-Sporting) group (the French Bulldog, Bulldog, Boston Terrier, Tibetan Terrier, Miniature Schnauzer, Shih Tzu, Lhasa Apso) the Dogue de Bordeaux, several Toy breeds (Pug, Chinese Crested, Chihuahua), the Belgian Malinois, a few hounds (Whippet, Beagle, Rhodesian Ridgeback), and three sporting breeds (English Cocker, Vizsla, and Labrador. (Numbers of some of these breeds have begun to fall off in the last few years, perhaps reflecting the end of a fad.)

Overall, however, the annual registrations of purebred dogs have been falling over the last decade in both the UK and US. For breeds that already fall in one of the FAO risk categories, this will only make matters worse. Again, the status of breed populations in other countries is essential to understanding the global risk to a breed, and compiling this information should be a priority.

It is important for breeders to know the risk status of their breed and take appropriate measures to stabilize population sizes by including more animals in the breeding program. Breeders also need access to the information and expertise necessary to develop strategies for sustainable breeding of both local and global breed populations. Protecting the size and quality of the gene pool will be an essential component of genetic management. Fortunately, breeders have become increasingly aware of the importance of managing inbreeding and the incidence of genetic disorders, and developing breed-wide strategies for genetic management will make both of these things easier.

As I have argued elsewhere, dogs need to be added to the list of domestic animal species that are monitored and protected as a valuable genetic resource. From the analysis here that shows most purebred breeds in the UK are at risk of extinction under the FAO criteria, it is evident that this needs to be done very soon. Declining populations, loss of genetic diversity, and the rising incidence of genetic disorders will make genetic management increasingly more difficult. The time to act is now.

| status_of_uk_breeds__beuchat_.xlsx |

- Lewis TW, BM Abhayaratne, and SC Blott. 2015. Trends in genetic diversity for all Kennel Club registered pedigree dog breeds. Canine Genetics and Epidemiology 2:13 (DOI 10.1186/s40575-015-0027-4)

FAO risk status of breeds in the UK

| Critical (n = 115) Affenpinscher Afghan Airedale Akita Australian Cattle Dog Australian Shepherd Australian Silky Terrier Australian Terrier Basenji Basset Fauve de Bretagne Basset Griffon Vendeen Grand Basset Griffon Veneen Petit Basset Hound Bearded Collie Bedlington Terrier Belgian Shepherd (Groenendael) Belgian Shepherd (Malinois) Belgian Shepherd (Tervuren) Black Russian Terrier Bloodhound Bolognese Borzoi Bouvier des Flandres Bracco Italiano Briard Brittany Bullmastiff Cesky Terrier Chesapeake Bay Retriever Chinese Crested Clumber Spaniel Cocker Spaniel American Coton de Tulear Curly-coated Retriever Dachshund long-haired Dachshund smooth-haired Dachshund wire-haired Dandie Dinmont Terrier Deerhound English Setter English Toy Terrier Eurasier Field Spaniel Finnish Lapphund Finnish Spitz Fox Terrier Smooth German Pinscher German Spitz Klein German Spitz Mittel German Wirehaired Pointer Giant Schnauzer Glen of Imaal Gordon Setter Greyhound Griffon Bruxellois Havanese Hungarian Puli Hungarian Wirehaired Vizsla Irish Red & White Setter Irish Setter Irish Terrier Irish Water Spaniel Irish Wolfhound Italian Greyhound Italian Spinone Japanese Chin Japanese Spita Keeshond Kerry Blue Terrier King Charles Spaniel Lakeland Terrier Lancashire Heeler Large Munsterlander Leonberger Lowchen Manchester Terrier Maremma Sheepdog Mastiff Mini Bull Terrier Miniature Pinscher Neapolitan Mastiff Norwegian Buhund Norwegian Elkhound Norwich Terrier Nova Scotia Duck Tolling Retriever Old English Sheepdog Otterhound Parson Russell Terrier Pekingese Pharaoh Hound Pointer Polish Lowland Sheepdog Portuguese Podengo Portuguese Water Dog Pyrenean Mountain Dog Pyrenean Sheepdog Saluki Samoyed Schipperke Schnauzer Sealyham Terrier Shiba Inu Skye Terrier Smooth Collie Soft-coated Wheaten Terrier Spanish Water Dog St Bernard Sussex Spaniel Swedish Vallhund Tibetan Mastiff Tibetan Spaniel Welsh Corgi Cardigan Welsh Corgi Pembroke Welsh Springer Spaniel Welsh Terrier | Endangered (n = 47) Alaskan Malamute Beagle Bernese Mountain Dog Bichon Frise Border Collie Boston Terrier Boxer Bull Terrier Cairn Terrier Chihuahua Chihuahua Chow Chow Dachshund mini smooth-haired Dachshund mini wire-haired Dachshund smooth-haired Dalmatian Doberman Dogue de Bordeaux Flat-coated Retriever Fox Terrier Wire German Shorthaired Pointer Golden Retriever Great Dane Hungarian Vizsla Lhaso Apso Maltese Newfoundland Norfolk Terrier Papillon Pomeranian Poodle Miniature Poodle Standard Poodle Toy Rhodesian Ridgeback Rottweiler Rough Collie Scottish Terrier Shar Pei Shetland Sheepdig Shih Tzu Siberian Husky Staffordshire Bull Terrier Tibetan Terrier Weimaraner West Highland White Terrier Whippet Yorkshire Terrier | Vulnerable (n = 4) Border Terrier Bulldog Cavalier King Charles Spaniel Miniature Schnauzer Not At Risk (n = 7) Chihuahua - smooth coat Cocker Spaniel English English Springer Spaniel French Bulldog German Shepherd Labrador Retriever Pug |

ICB's online courses

*******************

Coming up NEXT -

Understanding Hip & Elbow Dysplasia

Next class starts 25 April 2016

***************************************

Visit our Facebook Groups

ICB Institute of Canine Biology

...the latest canine news and research

ICB Breeding for the Future

...the science of dog breeding