|

But strong selection for production traits has a down side. Holstein cattle that have been selected for high milk production have low fertility, which of course is a problem if you want to make more Holsteins (Smith et al 2007). And one consequence of embryo transfer technology is that you can produce thousands of genetically identical cows, but when it comes time to breed all you have to work with are siblings. After a generation or two of sibling crosses, production declines, health declines, and entire herds can be ruined.

To restore health and vigor to their livestock, breeders can bring in fresh genes from the ancestral stock from which the modern breeds were developed. These old, less productive "heritage" breeds have significant value as a genetic reserve, a living vault containing the genes for hardiness, fertility, disease resistance, and other traits that might be lost under strong selection (Sponenberg and Bixby 2007). |

|

They found that many breeds were at risk of extinction or had already been lost. Some breeds were being replaced by commercial breeds that had little resistance to local diseases and did not do well in parts of the world where high-quality forage was scarce. Other breeds were waning simply because they were less profitable. The declining populations revealed a clear need to protect and preserve the original heritage breeds that were the living reserves of the genetic resources from which our domestic animals and plants have been developed.

In response, the FAO has developed information systems to monitor the global status and genetic diversity of populations of these heritage breeds. The centerpiece of the program is the Domestic Animal Diversity Information System (DAD-IS), which continuously assesses the management of genetic resources of domestic breeds in countries around the world.

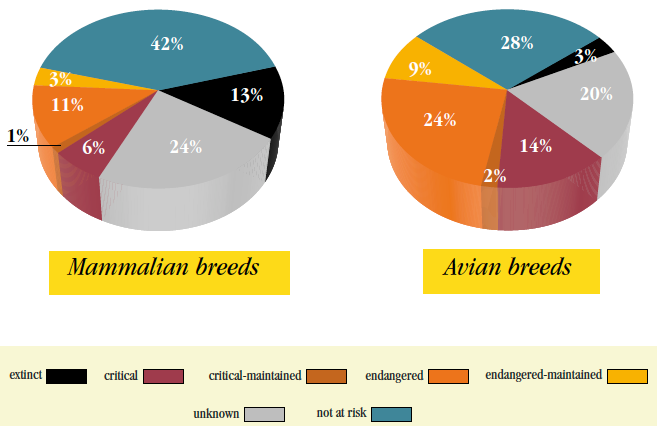

Using this information, breeds at risk are identified in the World Watch List for Domestic Animal Diversity (WWL-DAD), and strategies for supporting better genetic management are developed in cooperation with local partners. That these programs are critically needed is evidenced by the statistics: for domestic breeds of both mammals and birds, more than 50% are at risk, and in mammals 13% have already gone extinct. |

|

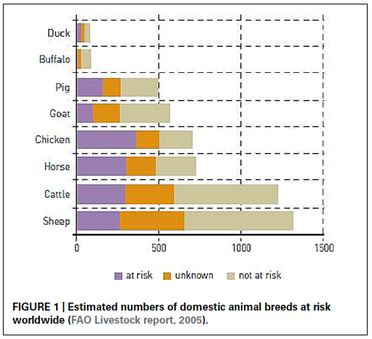

When the programs were set up to monitor the species and breeds that should be considered for protection as genetic resources, the FAO worried about cattle, sheep, horses, chickens, turkeys, ducks, goats, pigs, partridge, ostrich, llama, deer, rabbits, and even buffalo.

There are preservation programs for every species of domestic animal - except dogs.

|

In many parts of the world, and especially in regions that still rely on the resilient, locally-adapted heritage livestock breeds, dogs are essential for herding, protecting, and managing livestock.

Without dogs, protecting valuable animals from predation is done by killing the potential predators. Without dogs, moving the herds of animals the long distances necessary to follow seasonal forage is difficult or impossible. In many parts of the world, the success of animal agriculture depends on dogs.

Of course, dogs also have critical jobs in military and police work; they give mobility to the blind and comfort the sick, they detect cancer, drugs, and alien plants; they find the lost and run down poachers, and an endless list of other things.

|

But, for the most part, we are not.

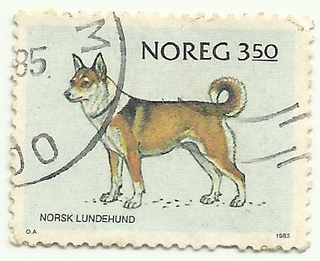

This group, together with the Norwegian Lundehund Club in Norway, has also initiated a program that is racing to rescue the Lundehund from extinction. The Lundehund is an iconic Norwegian breed that was used to hunt for puffins, which were were essential for survival over the cruel northern winters. But when Puffin hunting was banned, the dogs were no longer useful and just more mouths to feed. The population declined, barely survived a distemper outbreak, and finally dwindled to a only a half dozen, mostly related, dogs. A breeding program was started to save the breed from extinction, and all Lundehunds surviving today are descendants of those few dogs. But inbreeding has resulted in high puppy mortality and also a gastrointestinal malady (Lundehund syndrome) that is often fatal. The breed has very small numbers and the lowest genetic diversity of any dog breed (Melis et al 2012).

|

In 2013, the Norwegian Lundehund Club and the scientists involved in the Nordic dog breed program drafted a plan to outcross the Lundehund with the goals of preserving as much of the existing gene pool as possible and adding genetic diversity that would improve health and reproduction. So far, five breedings have resulted in only two litters and a total of eight puppies, so the battle to save this breed will clearly be uphill. But the effort has begun, and none to soon.

Is this a breed worth protecting? The Norwegians and the scientists certainly think so. How many other breeds of dogs are sliding down the slippery slope towards extinction as a result of small population size, inbreeding, and genetic disease? We don't really know. |

Outside of the UK, there are a few breeds in other countries receiving protection such as the Donggyeong in Korea and the Chongqing dog in China. But there are no global or even regional assessments of the status of the vast majority of breeds around the world, which number over 1,000 if you include the many (mostly working) breeds not recognized by a kennel club (Morris 2001).

Should we be worrying about preservation of dog breeds?

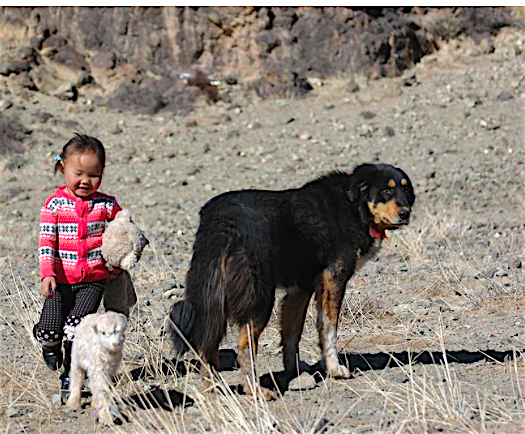

Are these breeds of dog really important? I think we can argue that many are. In Mongolia, for example, the nomadic herders have relied for thousands of years on an indigenous mastiff, the Bankhar, for protection of their families and livestock from wolves and leopards. These dogs are well-adapted to the harsh terrain and climate, and they have the strength and temperament to be effective deterrents to the wolves and snow leopards that would prey on livestock.

|

Unfortunately, the Bankhar dog was nearly wiped out during the Russian occupation of Mongolia, and shooting the predators became the only means of protecting livestock. Removal of predators has ripple effects that alter many aspects of an ecosystem - the populations of other prey animals, the vegetation, and the many complex interactions of plant, animals, and environment.

Three years ago, the Mongolian Bankhar Dog Project was launched with the goal of establishing a breeding population of Bankhar. The puppies produced are being homed with herders, they grow up as part of the herd, and they take on the duty of protection as adults. The project has just placed the puppies from the second breeding season. The Mongolian Bankhar dogs are returning to a job that humans can do only poorly, and the dogs can do it in a way that supports the local ecology. |

But now in many places the success of programs to protect and restore populations of wolves, bears, and other predators is once again increasing the predation on livestock. The inevitable conflicts are pitting ranchers against wildlife managers, and we are slowly coming to the realization that, in many cases, the ancient, traditional livestock guarding dog can enable livestock and predators to coexist. In Bulgaria, for example, conflict between shepherds and conservationists over ways to reduce predation on livestock led to the creation of an organization called Semperviva, which is breeding the traditional Karakachan dogs and providing puppies to the shepherds. Similarly, a group in Slovenia has formed a non-profit to support a genetically sound breeding program for the Karst Shepherd, which is an FCI recognized breed but suffers from inbreeding and a small population size.

|

Even private citizens have taken the initiative to start breeding programs for breeds in danger of extinction. Daniyar Daukey has started a breeding program for the Tobet in Kazakhstan. |

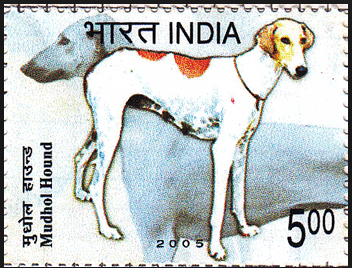

In Asia, the Dhangari dog of India, which was used for both herding and hunting, is only one of a number of indigenous breeds in danger extinction. Among the others are sighthounds (Kaikadi, Taji, Chippipaparai dog, Soriala Greyhound), mastiffs (Alangu and Himalayan mastiff), and herders (Maharashtrian Shepherd Dog).

Many of the terriers fall into this last category. No longer used for vermin control, they were found to be suitable as lap-sized companions. But strong selection and inbreeding have taken a toll on health, and declining numbers now threaten many of these breeds with extinction even as they remain popular as pets. Many terriers populate the UK Kennel Club's vulnerable breeds list, but with no plan to restore genetic diversity and reduce the incidence of genetic disorders, the future of many of these breeds looks grim.

|

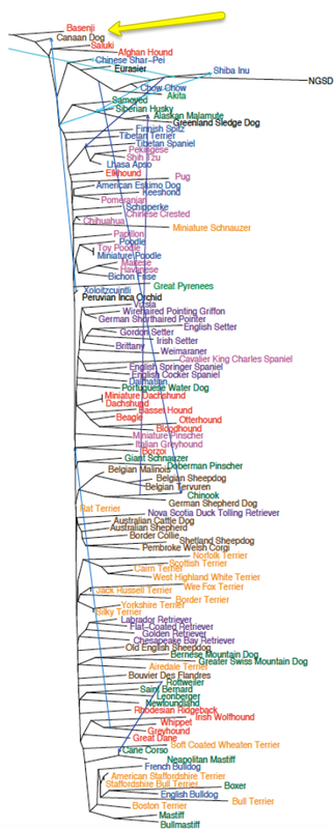

Perhaps our greatest concern should be for the breeds that modern molecular genetics is identifying as some of the most ancient.

Two landrace breeds, the Basenji and the Canaan dog, are the oldest of the extant dog breeds (yellow arrow in figure opposite). Both have become recognized as "purebred" dogs and have loyal followings among breeders. But the purebred populations suffer from low genetic diversity, and acquiring more dogs from the countries of origin is difficult. In the Congo, which is the central African home of the Basenji, war and civil unrest make it too risky for trips to collect new dogs to add to the registered population. And in the Negev where the Canaan dog is found, a decline in the number of Bedouin herders, as well as programs to eliminate dogs for rabies control, is making it more and more difficult to find dogs.

How "valuable" are dog breeds?

It does seem that, for a variety of reasons, we should be worrying about the long-term survival of many of the dog breeds of the world. But investment of resources in programs to prevent extinction must be motivated by criteria of value and loss.

If we lose a breed here and there, how much does it matter? Is one breed more valuable than another, and how would you judge? If the job is extinct should we be saving the breed?

These questions become much more difficult to answer if we recognize that we really know very little about what dogs are capable of doing. A dog that can detect the presence of cancer in a urine sample better than any existing technology has value to medicine that is difficult to estimate. Dogs can detect drugs hidden in cargo, they can find a fire ant in a field, and they can locate an invasive plant species hiding among native plants. Dogs can detect magnetic waves, they can read our facial expressions, and they can sense an imminent hypoglycemic crisis. Dogs trained to lie perfectly still in a MRI scanner are even contributing to a better understanding of the workings of the brain.

And then there's the huge role they are beginning to play in genetics research.

|

|

Because of selective breeding for specific phenotypes, it is likely that dog breeds will differ genetically in ways that could facilitate research of traits that would be otherwise difficult to study such as behavior, evolutionary adaptations to extreme environments, epigenetic processes, and the influence of the intestinal microbiome on disease and immunity. But really, we have no idea what the limits are of what we can learn from them.

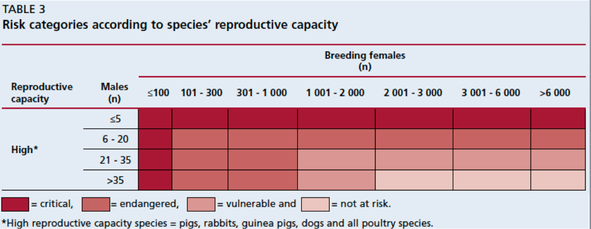

Even many of the breeds we are most familiar with, and which might seem to have abundant numbers, would be classed as threatened or endangered using the criteria for other domestic animal breeds. The FAO has developed a simple table for breeds of "high reproductive capacity" (i.e., produce litters of offspring versus only one or two at a time). Knowing the number of breeding males and females in the population, a breed can be assigned to a risk category. Done on a country-by-country basis, as is for other domestic animals, many breeds of dogs are going to find themselves in the danger zone.

There is no animal on earth with greater diversity in morphology, behavior, and the roles it plays in our lives. Certainly there is none that has played a more significant role in the development of human civilization. The value of the dog to us as an "animal genetic resource" is inestimable.

There are more than 400 recognized pure breed of dogs, and hundreds more that are not formally recognized but are essential as working dogs. Then there are the populations of village dogs around the world. These are not mixed breed, feral dogs, but animals that have been free-living in the vicinity of human populations for thousands of years. They carry the signatures of genetic ancestry that are now being used to piece together the evolutionary history of both dogs and humans, including where the first dogs were domesticated (Larson and Burger 2013).

Instead of breeding for perfection and purity, the most important - and urgent - consideration of breeders should be preservation. The loss of genetic diversity over time can be insidious, and genetic rehabilitation or restoration of a breed is difficult. Breeders reluctant to make the best use of genetic diversity existing in a breed because it involves using less than spectacular animals will find it infinitely more difficult to consider a genetic rescue that will require crossing to another breed.

Genetic management for breed preservation will require breeders to take a long view that considers the potential consequences of today's decisions on the breed generations down the road. It will require cooperation and transparency among breeders on both a regional and global scale. It will require educating breeders and finding appropriate rewards for good genetic management instead of ribbons for success in the ring. There are hundreds of dog breeds. This is going to require a serious and substantial commitment.

Dobson H, RF Smith, MD Royal, CH Knight, and IM Sheldon. 2007. The high producing dairy cow and its reproductive performance. Domest. Anim. 42 (Suppl 2): 17-23.

Larson G and J Burger. 2013. A population genetics view of animal domestication. Trends in Genetics 29(4): 197-205.

Melis C, AA Borg, IS Espelien, & H Jensen. 2012. Low neutral genetic variability in a specialist puffin hunter: the Norwegian Lundehund. Anim. Gen. 44: 348-351.

Morris D. 2001. Dogs: the ultimate dictionary of over 1,000 dog breeds. Trafalgar Square, North Pomfret, Vermont.

Shannon, LM, RH Boyko, M Castelhano, E Corey, JJ Hayward, and others. 2015. Genetic structure in village dogs reveals a Central Asian domestication origin. PNAS.

Sponenberg DP and DE Bixby. 2007. Managing breeds for a secure future: strategies for breeders and breed associations. The American Livestock Breeds Conservancy, Pittsboro, North Carolina.

ICB's online courses

*******************

Coming up NEXT -

Basic Population Genetics for Dog Breeders

Class starts 4 April 2016

***************************************

Visit our Facebook Groups

ICB Institute of Canine Biology

...the latest canine news and research

ICB Breeding for the Future

...the science of dog breeding