No disorder causes more pain and suffering in dogs than hip and elbow dysplasia. The Orthopedic Foundation for Animals was founded in 1966 specifically to address the growing problem of these two disorders, and although there has been some reduction in incidence in some breeds thanks to the efforts of breeders, after 50 years of research and selective breeding, hip and elbow dysplasia still remain at the top of the list of issues affecting the welfare of dogs.

This is a huge problem for breeders. Dogs with good hips can produce puppies with bad hips, and vice versa. Should dogs with less than stellar hip scores be removed from the breeding pool? What if the breed already has dangerously low genetic diversity and myriad serious health problems - is it worth taking a risk breeding a dog if it is matched with a dog with excellent scores? Should you breed a dog with one good hip and one bad one? What if a dog had bad hips but the rest of the litter had great scores?

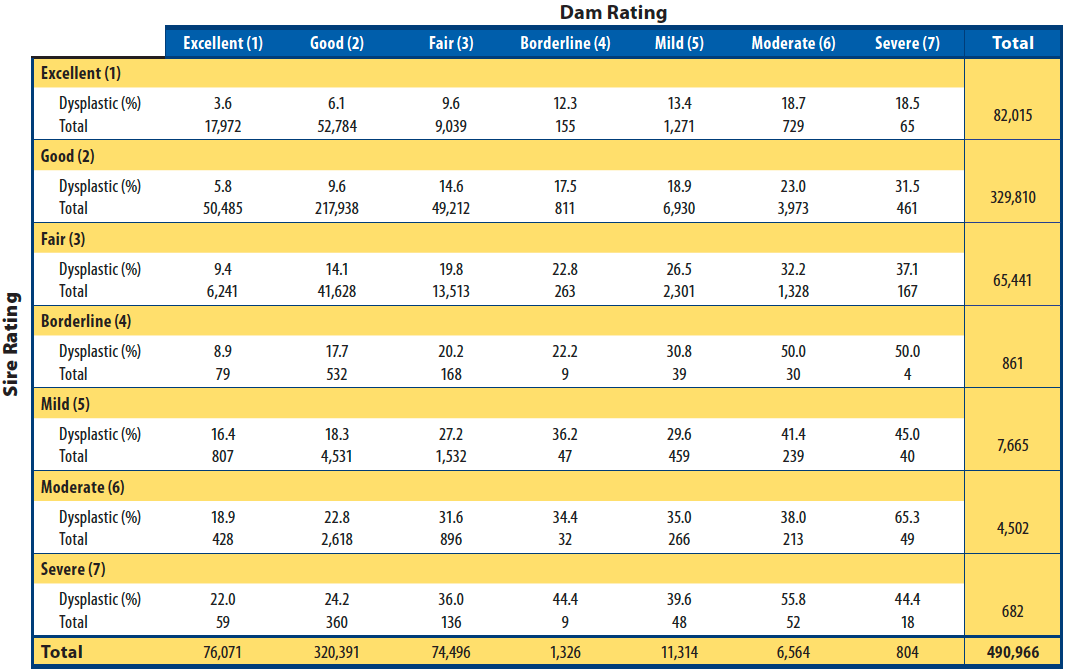

These are tough questions, and the conundrum is evident here in this table of data produced by OFA (Keller 2012). You can see that pairing two dogs with excellent hips will still produce some offspring (3.6%) that are rated dysplastic based on x-rays. And breeding two dogs with less-than-perfect hips (e.g., mild with mild) can produce some dysplastic dogs, but also still a majority (about 70%) with acceptable hip scores. Note that this might be an overly rosy assessment because of incomplete, biased data; if bad scores are not submitted, the fraction of dysplastic offspring will be an underestimate.

To breed or not to breed? It's a really tough question.

The economic consequence of hip dysplasia

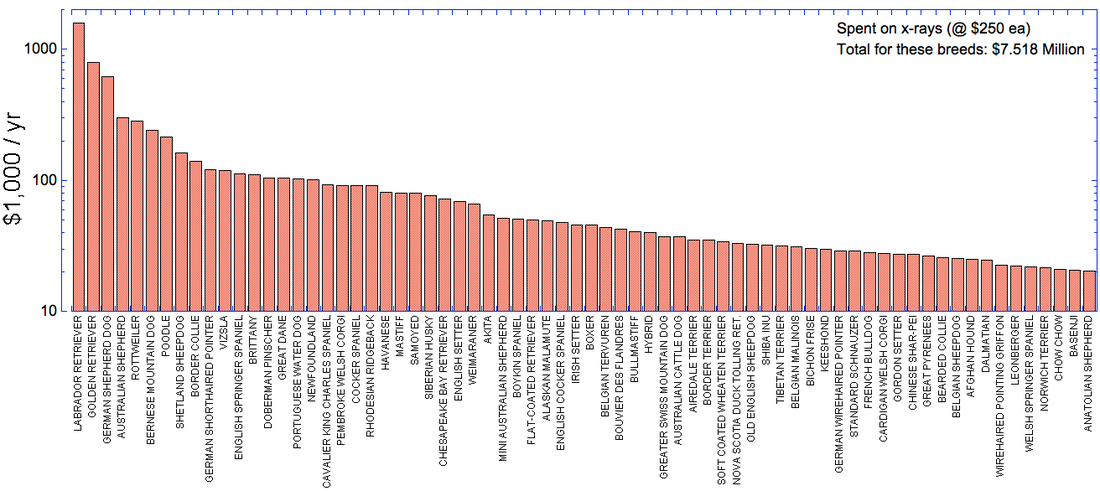

Of course, there is a cost to these problems. OFA provides the data for the number of dogs in their database by breed for the years 2006-2010, so these would be animals that submitted x-rays for evaluation. I assumed very conservatively that a hip x-ray costs $250, and multiplied that by the number of scans submitted per year over this period, separated by breed.

The numbers are staggering. To avoid using fractional numbers on the y-axis of this graph, I have logged that axis and run the scale from 10 to 2,000, and the unit is $1,000 per year. This means that 2,000 on the graph is $2 Million, 1,000 is $1 Million, and so on. X-rays for Labrador Retrievers alone over this 5 year period averaged $1.58 Million/yr. This is just for the dogs that submitted x-rays to OFA, which is certainly not every Labrador in the world that had its hips x-rayed (e.g., very poor results might not be submitted, and evaluations in other countries would not be in the OFA database). That number for Labradors - $1.5 Million, is only a fraction of the actual cost for the entire breed.

(You can download a larger version of this graph here.)

| 2015-09-05_2352.png |

Take a moment to let that number sink in.

The scary thing here is that there is no end in sight. This is costing us many millions per year, and we have to expect that this will continue for the foreseeable future. On top of that, we can't put a number on the suffering of the dogs, not to mention the heartache of a family that can usually do little to alleviate the pain. We can continue to get the x-rays done, and OFA and other health organizations can continue to collect the data, but are we headed towards a solution? I don't think so.

So, what can we do? Some very, very smart people have been thinking about this for decades. But sometimes fresh eyes coming from another perspective can see things that have been missed by others, and this can make all the difference. I'm not an orthopedist; I'm not even a veterinarian. But I am a biologist with broad expertise in vertebrate biology and a similarly broad approach to solving problems in science. Let me tell you what I saw when I started thinking about the problem.

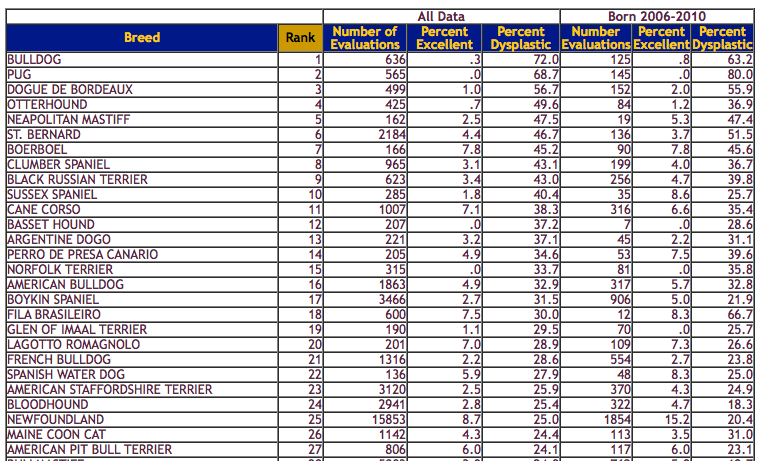

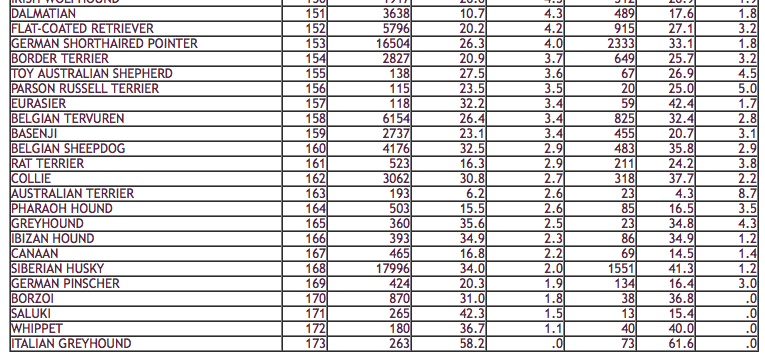

A few years ago, I was puttering around on the OFA website for some reason and happened to look at the statistics for hip dysplasia. The data are ranked, so the breeds with the highest frequency of dysplastic hips are at the top of the list. Hip dysplasia is a notoriously "large breed" problem, but what caught my eye was that the top 2 breeds on the list were the Bulldog and the Pug. Neither of those would have been on my list of "large breeds". Similarly, at the bottom of the list was another surprise. Among those breeds with the lowest incidence of dysplasia were the Borzoi and Greyhound; in terms of height, I would consider them large.

The message suggested by the data was clear. Hip dysplasia is not a "large breed" problem. Rather, hip dysplasia is most prevalent among breeds that are heavy for their size, whether they be large or small, and conversely dysplasia is rare in breeds of moderate to light build.

The phenotype and genotype of hip dysplasia

We know that both hip and elbow dysplasia are heritable; that is, genetics can account for some of the variation in the quality of these joints from animal to animal. But efforts to identify the genes responsible have been frustrating, because both problems are certainly polygenic, with dozens or even hundreds of genes involved, and there is no indication that we will ultimately identify a set of "risk genes" that we can simply select against in the relevant breeds.

Of course whether a breed has a light or heavy build is genetic, and within a breed there can be variation among individuals in what we call "substance". So I wondered - could the variation in build among and within breeds account for at least some of the variation in the incidence of hip dysplasia? Have we been looking for "hip dysplasia genes" when the responsible genes have nothing to do with hips, but instead determine the "robustness" of the dog? Could this be a biomechanical problem of weight relative to the size of the dog?

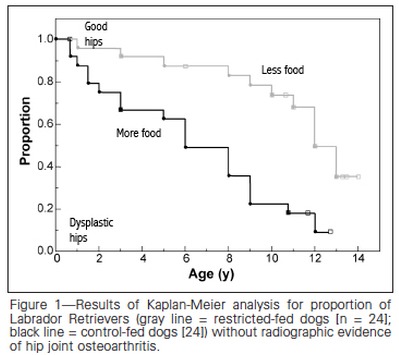

| Purina did an amazing experiment some years ago in which they raised Labrador Retriever puppies under two conditions (Smith et al 2006). (I've written about this experiment here as well.) From each litter, one pup went into a group that was allowed to eat as normal (control group), and its littermate was fed 25% less than the sibling (restricted food group). They followed these dogs for life, and the results were astonishing. Some dogs in the control group showed signs of hip dysplasia even as puppies, and by 6 years old half the dogs in this group were dysplastic. In the restricted food group, on the other hand, only about 10% of the dogs were dysplastic by 6 years, and at 12 years still only 50% were dysplastic. |

So we can expect the environment might have a significant effect on the quality of the hips, but what about genetics? Several studies have looked at this and found the heritability of hip dysplasia to range usually from about 0.15-0.4; that is, 15-40% of the variation in hip scores among dogs is accounted for by genetics. Genetics definitely matters, but are the genes breed-specific? Are they related to some aspect of hip development? Are they related to body "robustness"? Or maybe none of these?

Unfortunately, we don't have the data to answer this question, and it's not likely that someone will do another 13 year experiment like the one Purina did. But I don't think this necessarily leaves breeders twisting helplessly in the wind. We can be certain that food consumption matters. There is also some evidence of other factors such as type of exercise, stair-climbing, growth rate, and other things could be important, and some of these are things breeders can do something about if they are aware of the existing data and what it means.

Let's do some Citizen Science!

I think breeders can play a role in figuring out the most effective ways to reduce the incidence of hip dysplasia. After all, every breeding you do is a genetics experiment, and if you collect the right data we might be able to address some questions that would be nearly impossible to do any other way because of the time and expense that would be involved.

So here's my idea. I would like to do a Citizen Science project. I want to round up a group of breeders that have data for litters they have bred in the past for which the hips were evaluated. At the very least, we would want the pedigree information, but if there are data for growth (did you periodically weigh the puppies?), adult body weight, height, etc., we will collect that too. Let's gather together all of the data we can come up with (and you can provide not just your own data but perhaps also more from other breeders), do some analyses, and see what we can learn. Then I want at least some of these people who plan to have a litter in the near future to collect some specific data on those dogs as well. If we don't get enough participants and data for a particular breed, we won't be able to do much. But I think if we get the data collection started, we can build on it over however long it takes, and eventually (and I think it won't take long) we might learn some interesting things. The alternative, of course, is that nobody does anything, so even if this is far-fectched we don't have much to lose.

One thing that I think will be necessary as a part of this is to get breeders up to date on what is known about hip dysplasia. They will need to understand heritability in order to make appropriate breeding decisions. They need to understand the hip and femur anatomy in order to make sense of the role of biomechanics. They need to be familiar with the studies that have looked at various potential risk factors, as well as the cross-breeding experiments that have been done.

To this end, I've designed a new ICB course, Understanding hip and elbow dysplasia. Of course, anybody can take the course, but those that want to be a part of the Citizen Science experiment need to take it so all of us will be up on the information we will need to understand in order to design and interpret our data. What we learn from the project will depend on how much participation we have, but at the very least the participants will learn a lot and it might also be the beginning of a more systematic way of gathering information that is presently unavailable in any form.

So if you're interested in participating in a Grand Experiment in Citizen Science, please join us. I just set up the course registration page, and I'll form a private Facebook group where we can gather and discuss how to proceed. The course will have a separate group so communication will be easier, but I hope to see lots of you in both.

You can get to the Hip and elbow dysplasia course info page HERE.

- Keller GG. 2012. The use of health databases and selective breeding: a guide for dog and cat breeders and owners. Orthopedic Foundation for Animals, Inc.

- Smith, GK, ER Paster, MY Powers, DF Lawler, DN Biery, FS Shofer, PJ McKellvie & RD Kealy. 2006. Lifelong diet restriction and radiographic evidence of osteoarthritis of the hip joint in dogs.

******************************

Visit our Facebook Groups

ICB Institute of Canine Biology

...the latest canine news and research

ICB Breeding for the Future

...the science of animal breeding