Like the folks that live in the mythical town of Lake Wobegon, where everyone is “above average”, most people responded to the "Rate Yourself" post with a score of 3 or more on a scale of 1 to 5. And pretty much everybody said that the overall level of understanding of the people in their breed was low (lots of 1s for this).

The latter response is very worrisome. Here’s why.

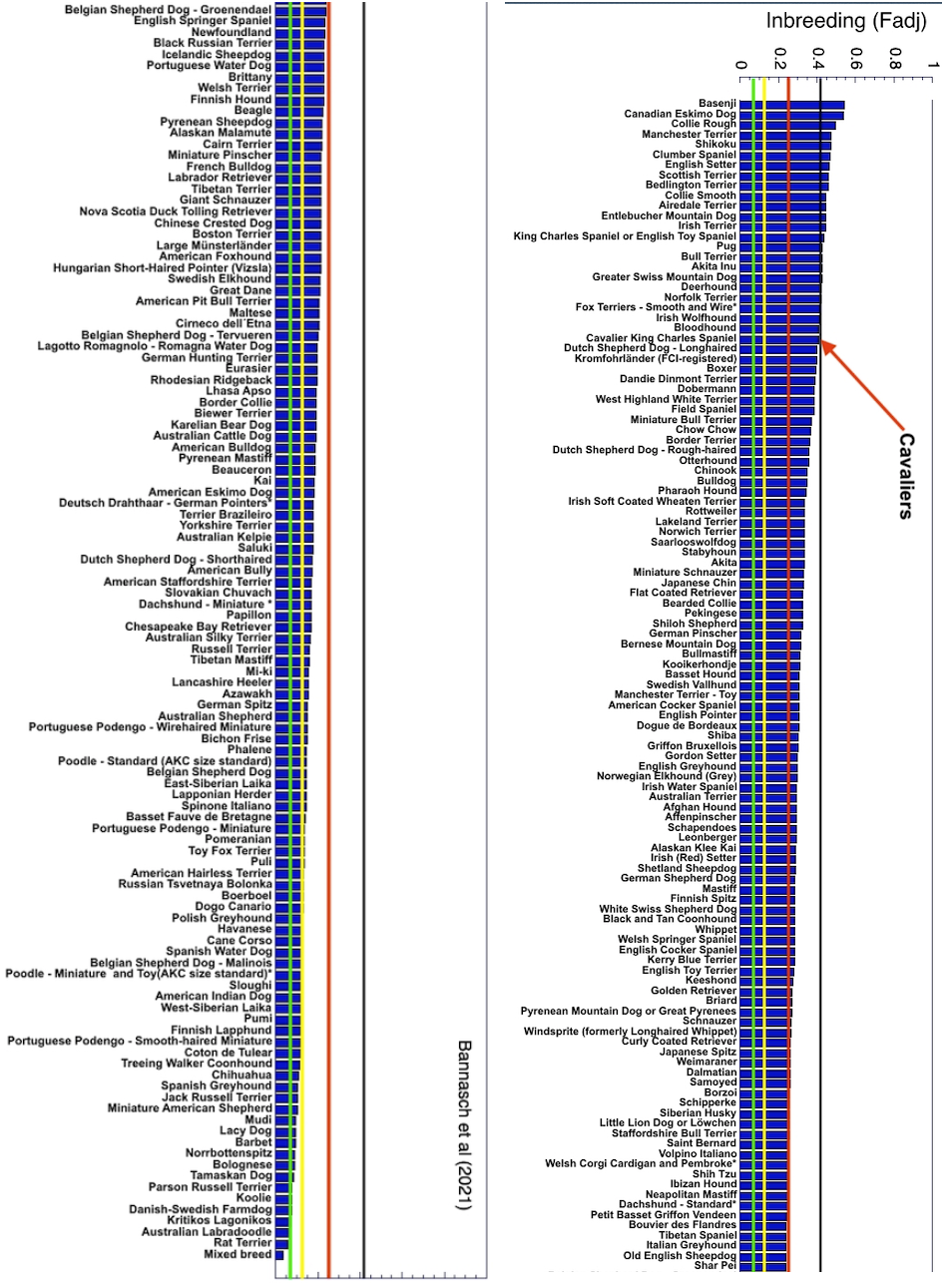

Find your breed on this graph, which is the genomic (from DNA) inbreeding of a large number of purebred dog breeds. These data are consistent with data from several other studies of different populations, so we can assume that this is a fair representation of inbreeding in these breeds.

The green line is inbreeding of 6.25% (mating of first cousins), yellow is 12.5% (mating of half sibs), and red is 25% (full-sib mating). (I made this graph to highlight the data for Cavaliers for another post; the black line at about 41% is the average inbreeding of this breed.)

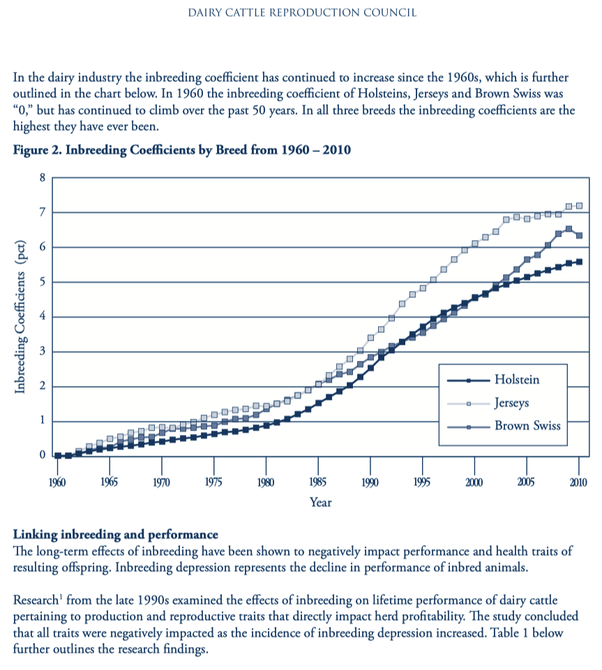

Inbreeding in dogs is FAR higher than in any other mammal, wild or domestic. Inbreeding of wild animal populations is usually in the very low single digits. Breeders of livestock begin to panic as inbreeding approaches 10% because the negative effects are so significant. In fact, they worry about every percentage point of increase; on this chart, the livestock people are wringing hands because "in all three breeds the inbreeding coefficients are the highest they have ever been," and they haven't even cracked 10% yet.

Can we at least say that we are breeding responsibly, i.e., making breeding decisions that will limit the damage to a breed’s gene pool? Let’s look at some data.

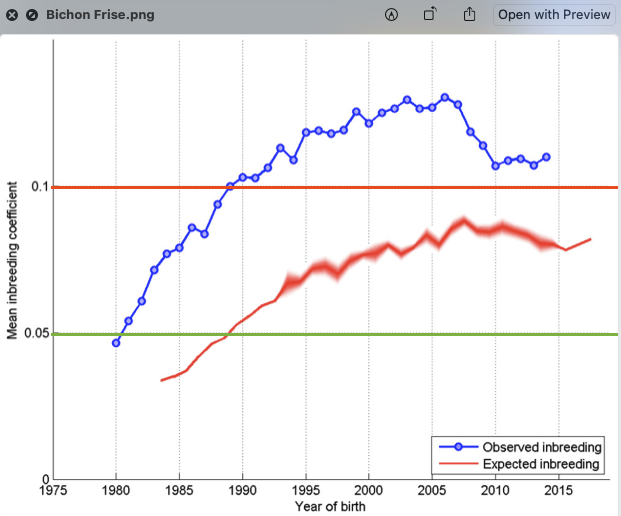

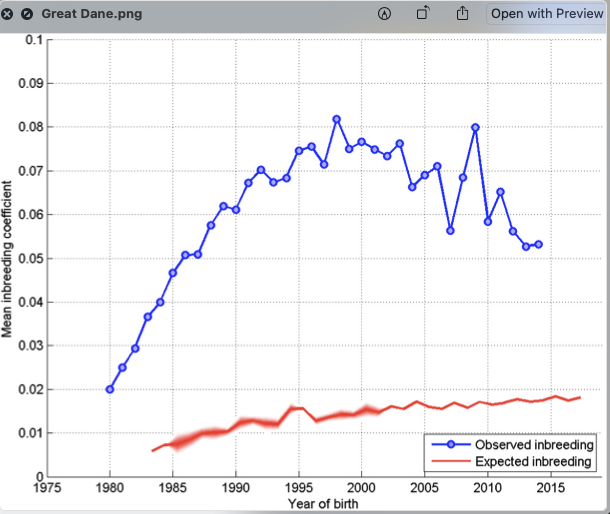

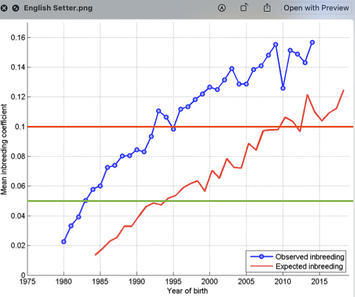

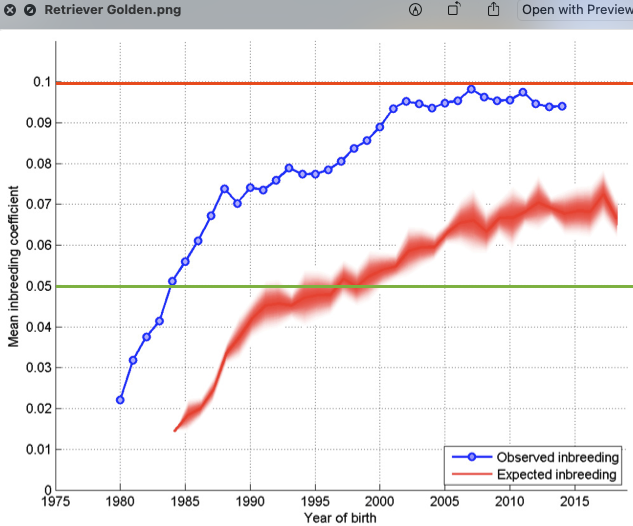

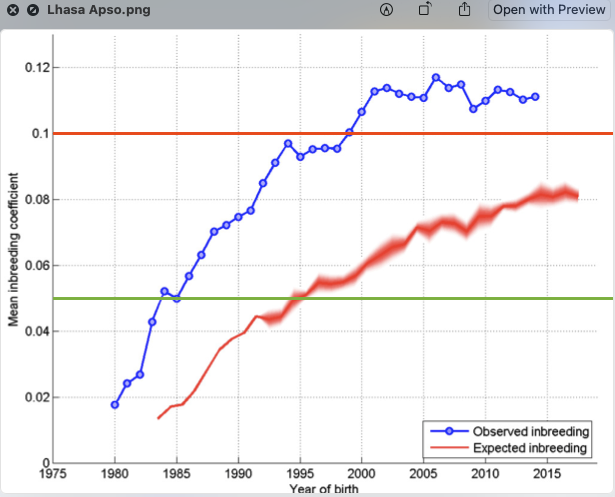

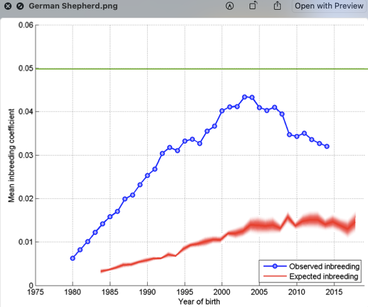

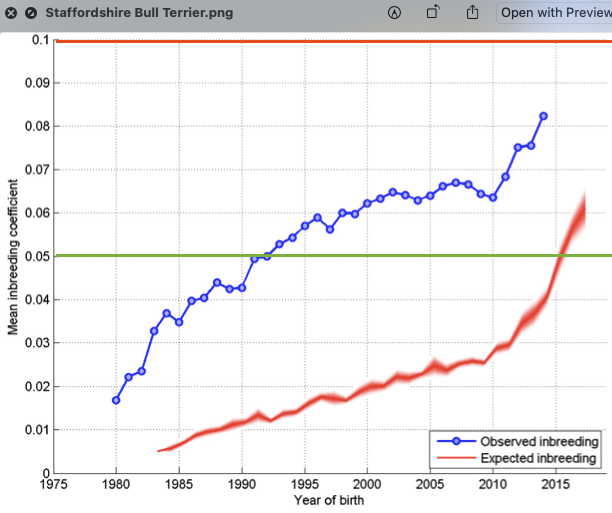

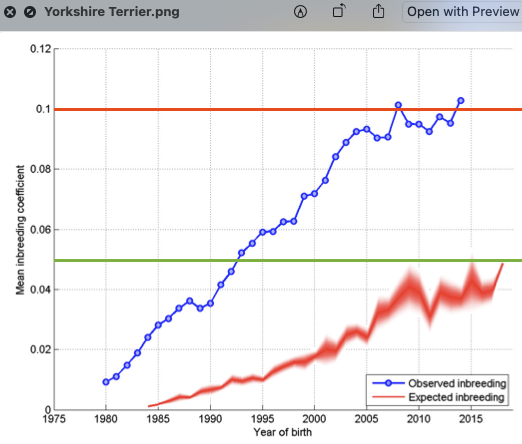

These graphs are from Lewis et al (2015) and are based on the pedigree records of the UK Kennel Club. Note that the data were not digitized before 1980, so the graphs start there, and the COIs are much lower than actual values because the ancestors from 1980 back to founders are not included in the calculation. Also, ban on importing dogs into the UK was lifted in 2000, and the incomplete pedigree data for those dogs make it look like the average population inbreeding is going down after that, which is probably not the case.

The blue line is the average COI computed from the pedigree data. The red line is the level of inbreeding that would be expected if the dogs in the population were breeding randomly. If breeders were making a strong effort to avoid inbreeding, the blue line would be below the red line; if breeders are preferentially breeding dogs that are more closely related than average, the blue line would be above the red line.

These graphs tell us about the overall breeding strategies being used in each breed. Breeders are preferentially inbreeding. (I have grabbed a few of the breeds that have a population large enough to show a trend instead of a line that goes all over the place.)

(Graphs from Lewis et al 2015, Additional Files)

In response to the ban on breeding Cavaliers and Bulldogs in Norway, the clubs have responded that the breeders are in the best position to solve the problems and are working hard to do this. But inbreeding will continue because it is unavoidable in a closed gene pool. DNA testing can prevent disorders caused by a single, recessive mutation for which we have a test, but we do nothing to control the many other recessive mutations we know are lurking in the gene pool, and selection is doing a poor job of managing the problems that are likely polygenic. Plus, we are preferentially inbreeding, increasing the risk of producing genetic disorders from mutations we don't yet know about.

I noted up at the top that, in a survey of the people in my Facebook group, ICB Breeding for the Future, most people rated their understanding of the principles of genetic management and breeding for health at a 3 or higher on a scale of 1-5, where 5 is highest. They also overwhelmingly rated the average understanding of the people in their breed at 1.

If we want to have purebred dogs, we need to solve some serious problems, we need to get it right the first time, and we need to do it soon. The kennel clubs say “We can do this,” but breeders assess the general level of genetic management expertise of their colleagues as rock bottom.

I can probably count on one hand the number of dog breeders I know that have enough expertise in population genetics to “know what they don’t know,” and all of those people are professional scientists that happen to also breed dogs. Beyond that, there is an army of “Facebook experts” - people that might know something about little bits of a topic but dispense advice as if expert. Invariably, they say things that are incorrect, because they don’t know enough to appreciate the nuances, complications, and depth of concepts. They don’t know what they don’t know, and most people don't know the difference. These experts don’t do any topical coursework (e.g., I don't see them in ICBs online courses for breeders), and they usually have no background in science at all. What they “know” has mostly come from things they read on Facebook written by other people with no expertise.

If you are tackling a very difficult problem, and if getting it wrong could result in catastrophe, these Facebook experts are extremely dangerous. Most breeders in my survey judged the expertise in their own breed as very poor. Most probably wouldn’t know good advice from bad; they are likely to be most swayed by things that sound “logical” or “make sense”. But their perspective is on managing the genetics of individual dogs. The genetics of populations are quite different, and indeed “the right thing to do” can often be counter-intuitive. You’ve heard that you should only “breed the best to the best”, but this will actually make it harder to improve traits and will ultimately lead to extinction of the population. In fact, this is why we are in this difficult spot, and continuing to use this breeding strategy is the hammer that will sink the last of the nails into the coffin. This is not an opinion; this is a necessary consequence of the mathematics behind population genetics. If you don't know this, then the "best to the best" advice seems like a good thing to do. But it's not.

The Norwegian kennel and breed clubs argue that they can fix the health problem of Cavaliers and Bulldogs by continuing to do the things they think will work. They haven’t worked so far, and they won’t. But apparently they don’t know that.

The Norwegian court offered that crossbreeding to solve the health issues would be allowed, but the feedback on Facebook has been adamantly opposed to even considering cross breeding programs. So, if the Norwegians have a plan to fix this without crossbreeding, I would like to hear how they will do it.

The breeds in the spotlight in Norway have to come up with a plan to address the issues that put them in violation of the Norwegian Animal Welfare Act. The Norwegians are on the hot seat right now, but every breed has an inbreeding problem that is incompatible with sustainable breeding, incompatible with “preservation” breeding, and incompatible with health. What breeds have a plan to address their growing list of genetic health issues, which will only continue to grow? How will they know if their plan will work? What will they do if it doesn’t?

Then, once we have inbreeding down to a reasonable level, we need to breed sustainably, which means we have to control inbreeding and loss of genetic diversity. To do this, breeders will need to understand population genetics, which provides the tools used for the genetic management of animal populations.

Are you thinking you already know a lot about population genetics? Among the essential topics you should be able to explain and discuss are these, for example: linkage disequilibrium, founder genome equivalents, effective population size, the Hardy-Weinberg equation, heritability, fitness, mean average kinship, observed and expected heterozygosity, and genetic drift.

|

There aren't many ways for breeders to learn population genetics, which is mostly advanced topics based on mathematics. When I was unable to point breeders towards a resource for learning about population genetics at a basic but useful level, I created some online courses specifically for dog breeders with no background in science. While I realize this looks self-serving, it really is the only option available to dog breeders without a degree in biology. Find the time to invest in education; the payoff will be immediate and continue for as long as you breed. Be an education advocate within your breed; you and your fellow breeders all must share a single gene pool, and breeders won't support a breeding strategy they don't understand.

The next ICB course for dog breeders about genetic management is "Strategies for Preservation Breeding," which starts 1 July 2022. Register now! |

Bannasch E et al 2021. The effect of inbreeding, body size and morphology on health in dog breeds. Canine Medicine and Genetics 8:12. doi.org/10.1186/s40575-021-00111-4

Lewis et al 2015. Trends in genetic diversity for all Kennel Club registered pedigree dog breeds. Canine Genetics & Epidemiology 2:13. DOI:10.1186/s40575-015-0027-4

ICB's online courses

***************************************

Visit our Facebook Groups

ICB Institute of Canine Biology

...the latest canine news and research

ICB Breeding for the Future

...the science of animal breeding