As the list of known genetic disorders in dogs continues to get longer, it's tempting to think that most of the nasty mutations lurking in the gene pool of a breed have already been found. The number of possible mutant genes must be finite, and surely we must be close to getting things under control. Or not?

If you haven't taken (and survived) a biochemistry course, you probably know very little about the inner workings of the cell and all of the various chemical processes that must be executed perfectly. If you ask how all this works, the short answer is that it's complicated. Really, really complicated.

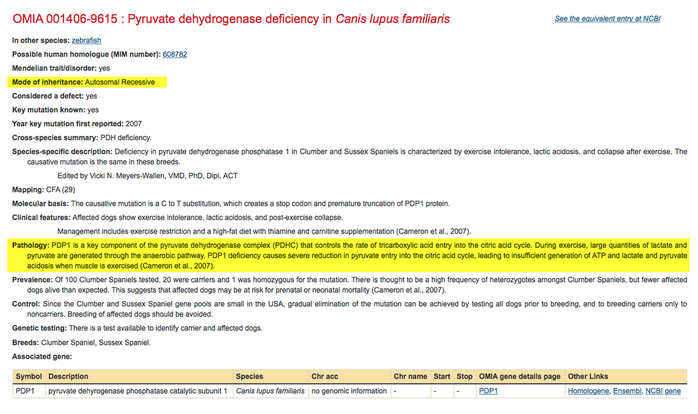

For instance, let's look at a genetic disorder caused by an autosomal recessive mutation that changes the genetic code of a particular gene by only one base (a C to T substitution), and this causes the protein made by this gene to be formed improperly. The protein is an enzyme called pyruvate dehydrogenase phosphatase 1 (PDP1), a long name for a molecule with the simple job of removing the equivalent of a water molecule (-HOH) from the compound pyruvate. This mutation causes exercise-induced collapse (EIC), which has been reported in a number of breeds, and is recorded in the database Online Mendelian Inheritance in Animals (OMIA):

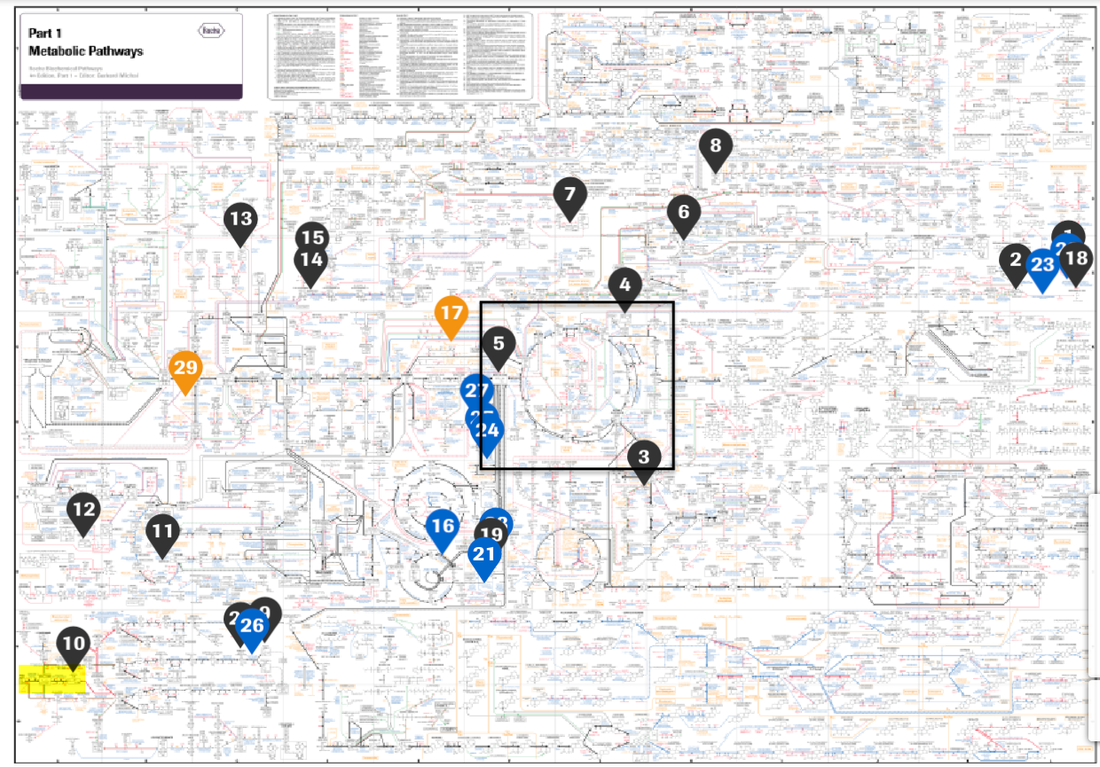

Let's have a look at what PDP1 does. Below is a schematic of metabolic pathways in the cell that looks like a map of the New York city subway system; don't let it confuse you. The thing to notice is that it's complicated (!), but we're going to look at just a tiny piece.

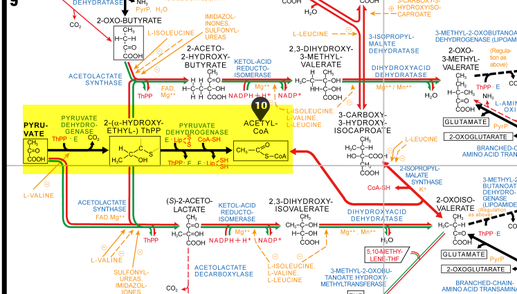

In the highlighted area below, you can see the molecule pyruvate on the left, and its conversion into a molecule called acetyl coenzyme A (Acetyl CoA) by pyruvate dehydrogenase.

So if there's a mutation in the PDP1 molecule, the enzyme won't work properly and pyruvate doesn't get converted into Acetyl-CoA. Then the question becomes how important is Acetyl-CoA?

We've been looking at just a tiny part of the network of biochemical reactions that occur in the cell as the process of metabolism. Here's a broader view below, with the highlighted steps again in yellow, and there is now a box around the circular series of steps called the "critric acid cycle" right in the middle. Enzymes on this chart are blue markers, and all the places where Acetyl-CoA appears are numbered as black markers. (You can explore the map here.)

Remember from the information in OMIA above - this is a single base change in the PDP1 molecule, and the mutation is expressed as an autosomal recessive. So if one of the alleles of the gene is a functional copy, a dog is not affected; two copies though, and you have exercise-induced collapse. Of course, a mutation like this would be strongly selected against, because it produces profound dysfunction if homozygous, so we would not expect it to be common in a population of animals. But in purebred dogs, the breeding of relatives ups the odds of producing animals with a double dose of the mutated allele, and that's why we're seeing it in various breeds of purebred dogs.

You don't have to squint hard at this chart of metabolic pathways to be awed by the number and complexity of chemical steps that have to occur in just the right sequence and at just the right rate to produce the energy a dog needs not just for exercise but for life. Everywhere you see that blue enzyme marker is another protein that can be broken by just the tiniest little error when it is produced. And these are just the pathways for energy metabolism in a cell. There's an equally tangled chart on the Roche website for cellular and molecular processes.

When I took biochemistry, I could envision all of these processes in my head, following a molecule through steps that remove a water molecule, add a hydroxyl group, clip off a hydrogen, and spin off those ATPs that are the currency of life in our bodies. The complexity fascinated me, and it does even more so today as I learn about the many little glitches that can result in a dog with a disease. And looking at that chart, it's humbling to think that there must be many, many ways the whole process can be broken by just the right mutation in a critical step. I'm sure we've only just begun to scratch the surface.