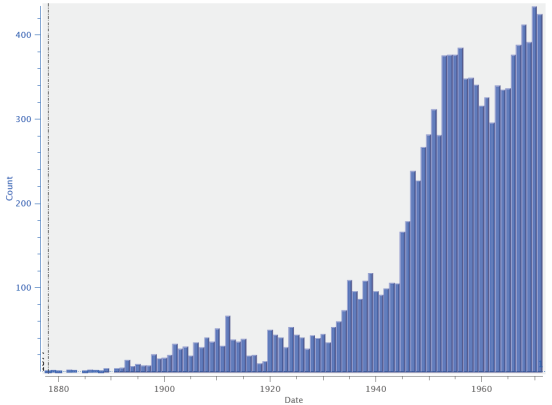

Every breed has a history that has shaped the population of dogs we have today. For breeds recognized by kennel clubs, some number of animals were selected to be the founders of the "pure breed" and registered in a stud book. All subsequent members of the breed must be able to trace their lineage directly to these original dogs, and this is assured by the requirement that only dogs with registered parents can be registered themselves. The nice thing about this is that we should have very complete records of a breed's history that can be used to understand how a breed has changed genetically over time. (In fact, there are surprisingly few complete pedigree databases that are publicly available, much to the detriment of effective management of the breed. A topic for another day...)

One of the first things we do at the Institute of Canine Biology as part of the genetic analysis of a breed is look at how the population has changed over time. (You can see several of these ongoing analyses under "Breed Projects" on the ICB website.) They are always very revealing and often there are some real surprises.

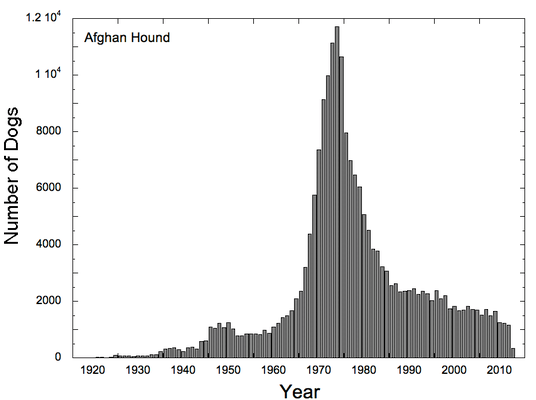

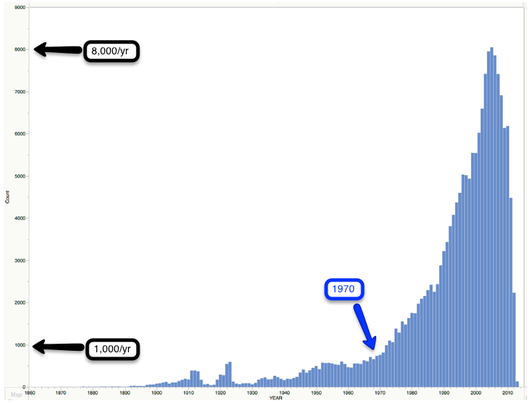

Then, even more rapidly than they increased, Afghan registrations dropped, to about 5,000/yr by 1980 and half that by 1990. Over a period of just 30 years, the breed experienced a boom and bust of truly epic proportions.

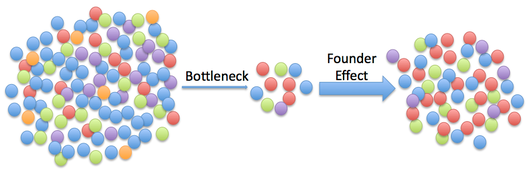

You've probably heard about founder effects, popular sires, and bottlenecks. A few popular dogs become overrepresented on the increase, and less popular lines die out on the downslide. These dramatic swings in the size of a population can wreak havoc on genetics.

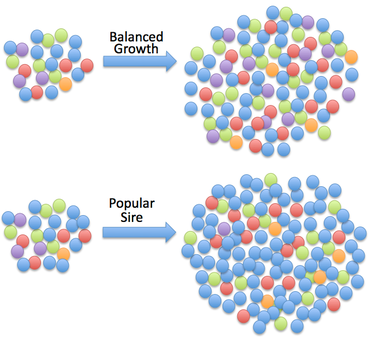

When a population grows by balancing the contributions of all of the dogs to the next generation, the frequency of alleles in the gene pool stays about the same as it grows. But if there is selection on a particular feature, or a popular sire, the genetic balance of the gene pool will shift, with the frequencies of some alleles increasing while other alleles become rare or are lost entirely. The nature of the gene pool of the population at the peak of its growth can be dramatically different than it was before the surge in popularity.

One thing that's important to remember is that the larger the swings in population size, and the faster they occur, the more dramatic the consequences can be for the gene pool. A gradual increase in population size is more likely to include a broader mix of animals, and likewise for a slower decline. Explosive growth and rapid crashes can change the composition of the gene pool dramatically.

For these and many other breeds, explosive surges in population size are usually followed sooner or later by a fall that can be equally dramatic, and the gene pool we're left with isn't the same as the one we started with. The dogs might look the same, because we have been carefully selecting for the genes for type, but the reservoir of genes that run the rest of the dog - physiology, immune system, organ function, temperament - can be only a tiny subset of what we had before. Today's breeders, trying to use the husbandry methods handed down from generations of dog breeders, find themselves in genetic cul-de-sacs from which there seems to be no escape, or engaged in a game of genetic whack-a-mole, defeating one nasty recessive mutation only to have another pop up in what was thought to be a "healthy" line.

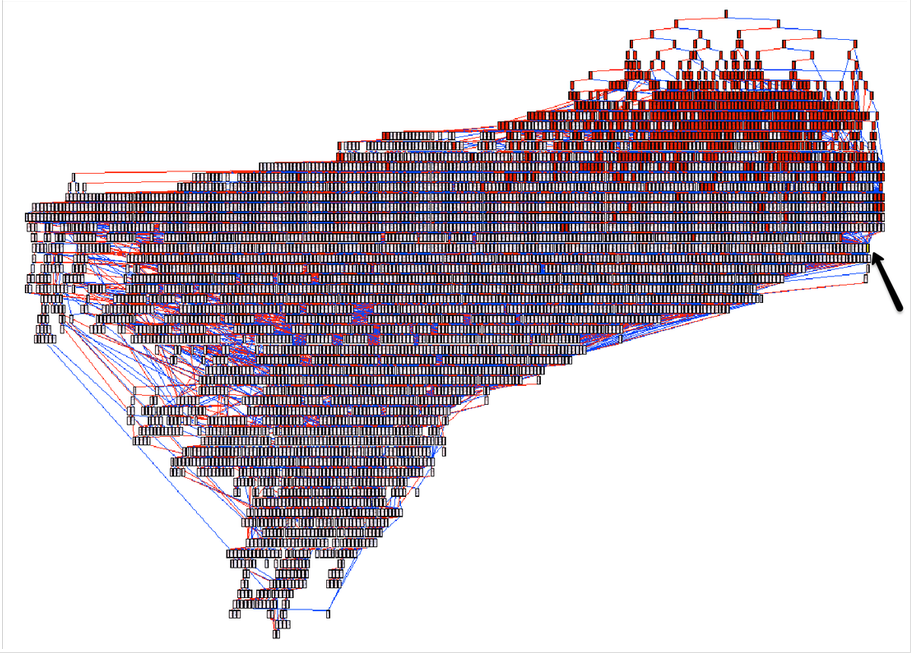

For most breeds, It's not your grandpa's gene pool any more. Like the cheetah and Przewalski's horse, the populations might appear robust and healthy, but because of their history, the genetics that support them are precarious. Protecting these breeds will require more vigilance now, and more cooperation among the breeders who have a collective desire and responsibility to protect the genetic heritage of our breeds. At the very least, we should be monitoring breed populations in the same way that we keep an eye on the gray whale and Mountain Gorilla. We should be able to identify in real time impending bottlenecks developing from popular sires, genetic lines in danger of extinction, dangerous levels of inbreeding, the emergence of new genetic disorders long before they are epidemic, and the booms and busts that can drive the genetics of a breed in an unwanted directions.

Think about the history of your own breed, and how your genetic landscape has changed over the generations. Assess what you have today, the problems that need to be tackled, and the path breeders need to take in the future to protect and improve on what we have. Collective efforts can be very powerful, and the payoff will come in securing the genetic resources of the breed for the future.

| ICB Institute of Canine Biology ...the latest canine news and research ICB Breeding for the Future ...the science of animal breeding |