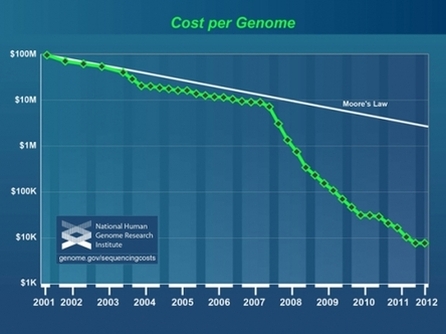

The first complete sequence of the human genome was completed in 2003, taking 13 years and $3-billion. By 2007, the cost had dropped to about $10-million. Then, in 2007, the development of a revolutionary new technology (called “Next-Generation Sequencing, NGS) sent the cost plummeting. By 2009 the cost was down to $100,000, and there is every reason to expect that within the year, you can sequence your entire genetic code for $1000. And it will continue to get even cheaper.

The line for Moore’s law on the graph reflects the cost of computer chips, which drops by half about every two years. Note that the axes of the graph are a log scale, so the slope of Moore’s law is actually exponential. The cost of computing power is declining at an astonishing rate – and since 2007, the cost of gene sequencing has been going down even faster.

There is a similar revolution underway in the breeding of both animals and plants. For livestock breeders, it means they can now use genotype information to assess breeding stock, and they can determine the quality and characteristics of the offspring at birth – from a blood sample or cheek swab – instead of waiting until three years later at maturity. They can select for particular traits with much greater efficiency, because there is no guessing about what alleles the parents carry. (There’s a nice, basic review of how molecular genetics is transforming cattle breeding here. ** You should read it, because this is coming soon to the world of breeding dogs!)

The first dog genome was sequenced in 2004, and in less than a decade the dog has supplanted the mouse as the model organism for the study of genetics. First, it turns out that humans are more similar to dogs genetically than they are to mice. And studying particular genes in mice required the breeding of special populations that were selected for particular genes, which took space, time, and money. In dogs, on the other hand, there are many genetic traits that are characteristc of individual breeds that can be studied with just a routine blood sample, taken from a family pet that goes home at the end of the day to sleep on the sofa. For scientists, there are no animals to house, no breedings to do or offspring to raise, very little trouble, and essentially no expense at all.

Together with modern molecular genetics, dogs are driving a revolution in our understanding of human genetics. But along the way, we’re learning a lot about canine genetics that can be put to good use by dog breeders. Identifying the gene behind a particular trait can now be done using cheek swabs from a few dozen animals in a few months or even weeks. We can begin identifying the genes associated with non-Mendelian and polygenic traits. This is information dog breeders can start using to take some of the guess-work out breeding, to make better predictions about the qualities in their next litter, and to breed healthier, happier dogs.

It’s an exciting time to be a dog breeder. Things are possible now that you could only dream about even a few years ago. Breeders need to start working as partners to the scientists, so that the science being done will be useful to the breeders and not just some data in a publication. And scientists need to start partnering with the dog breeders, who know stuff about dogs that scientists will never learn any other way.