Many canine genetic disorders are caused by autosomal recessive mutations. A dog with only one copy is usually unaffected if the other copy of the gene is the normal version. But if two animals that both have one copy of the mutation are bred, there is one chance in four that an offspring will be affected because it receives two copies of the mutation. This is from the simple Punnett square - 25% of the offspring will get two copies of the normal gene, 50% will be carriers, and 25% will be homozygous for the mutation.

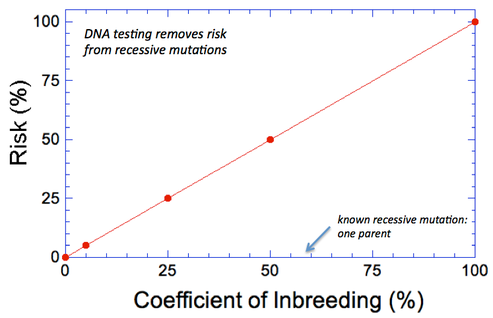

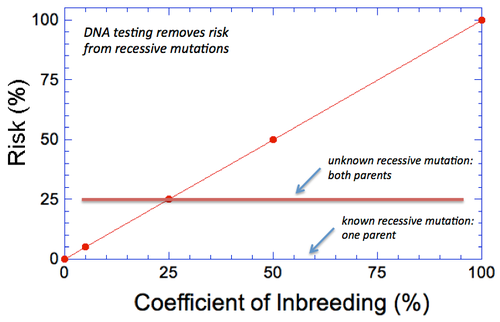

With the availability of DNA tests for many genetic disorders caused by autosomal recessive mutations, breeders can determine the carrier status of a dog and completely eliminate the risk of producing affected animals. Because these DNA tests reduce the potential risk of producing an affected dog from 25% to 0%, they are a very powerful way to manage specific genetic disorders in purebred dogs.

Unfortunately we have DNA tests for only a fraction of the known mutations in dogs, and there are probably hundreds more recessive mutations lurking in the gene pools of our dogs that we know nothing about. It's easy to see how we can manage the risk of problems from recessive mutations that we can test for, but what can we do about all the ones we don't?

This is a really important question, and one we don't often consider. The question we should ask first is whether we really need to worry about those unknowns. We don't know what they are or what problems they might cause (and of course, a mutation might be "neutral" and not cause a problem at all), so how big of a problem could they be? Consider that the mutations that we now have tests for only showed up on the radar because people starting seeing dogs affected by a genetic disorder. Before this, the mutation could have been passed from parent to offspring without harm for dozens or even hundreds of generations. As a general rule of thumb, we can expect every animal to carry a few mutations that would be lethal in a homozygous offspring, and many more will have some significant impact on health. So there are no doubt many, many more recessive mutations in the genomes of our dogs that will surface and cause problems if puppies get two copies.

If we can agree that we should assume that the genome of every dog will carry some mutations we don't know about that have the potential of causing trouble, then it is important for us to consider the risk not just from known mutations, but from those unknown mutations as well. We know that we can reduce the risk of affected offspring to zero with a simple DNA test, and that is certainly worth doing. But what can we do about the mutations we can't test for? Can we do better than just cross our fingers and hope?

Fortunately, we can. We understand how recessive mutations work. Puppies that get two copies will be affected, so our goal should be to find a way to reduce the risk of breeding two carriers. (There is no risk from breeding a carrier with a dog that is clear of the mutation.) But since we can't know who carriers are, or how many there might be in the population, how can we approach this problem?

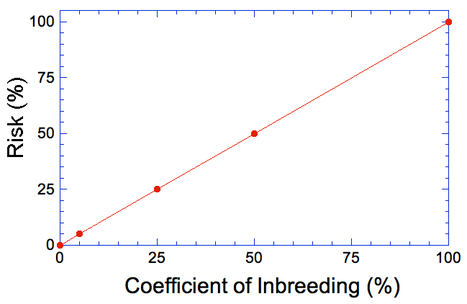

Now, how do we deal with all of the mutations we don't have tests for? These will behave as we described above - the COI of the puppy (the probability of homozygosity) will be the same as the risk of being affected. The higher the COI, the greater the risk of producing puppies affected by some genetic disorder caused by one of the recessive mutations that we know nothing about.

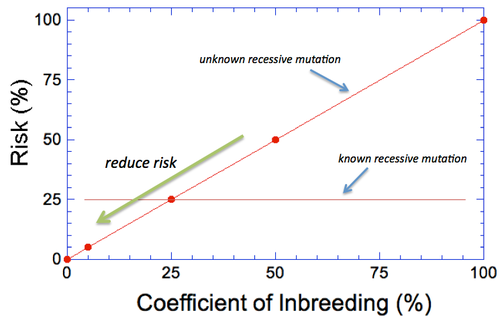

A responsible breeder can't know the risk of producing affected puppies from an unknown mutation, but they CAN manage that risk, and the rule is simple:

Risk goes down when COI goes down, for both the known and the unknown mutations.

This means that you can reduce the risk of problems from any and ALL recessive mutations by reducing the COI of the litters you produce. Instead of adding each new DNA test to the expense of health testing your dogs, you could effectively manage the risk of genetic disease by managing the risk of homozygosity, using COI as the yardstick.

If you're paying to do DNA testing, don't turn around a breed a litter with a COI of 25% or more. You will have paid to swap a known risk with an unknown one. If the known risk was worth the cost of a test, consider also the value of reducing the unknown risks. Larger litters of healthier, more fertile, and longer-lived puppies can be had simply by reducing COI. That's a great payoff, and it won't cost you a thing.