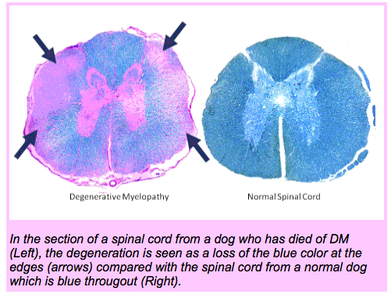

Degenerative myelopathy drew some interest from medical geneticists because it appears to be similar to the disorder that occurs in humans called amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), also known as Lou Gehrig's disease after the famous baseball player who succumbed to it. Stephen Hawking, the famous cosmologist, also suffered from ALS.

ALS is a devastating disease. It causes the death of motor neurons, which control the voluntary muscles. Without functional motor neurons, there is no ability to communicate with the muscles and the result is paralysis. It usually strikes in adulthood, in both humans and dogs, and degeneration is progressive.

In Corgis, disease onset was usually in dogs older than 8 years. Of course, the dog would have been bred by then and produced puppies that could be at risk. A test was developed for the newly found mutation and breeders were encouraged to test their dogs before breeding.

Bernese Mountain Dog also had a high frequency of DM, but the available test was not accurately assessing risk. Further study revealed a different mutation of the SOD1 gene that appears to be unique to Bernese Mountain Dogs (Awano et al. 2009; Zeng et al 2014). A specific test was developed for that breed as well.

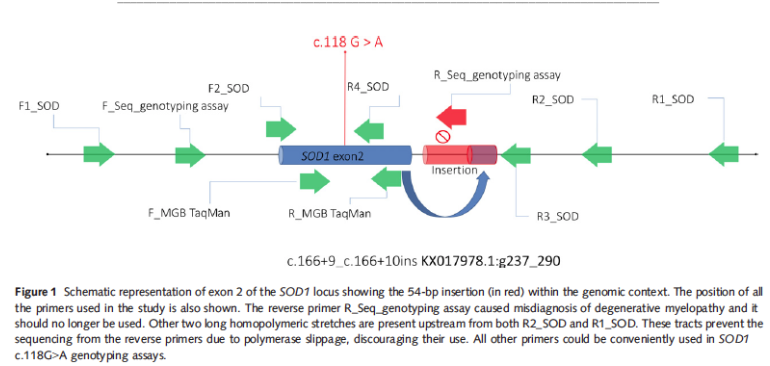

Things got more complicated when researchers started noticing discrepancies between test results and the genotype expected of dogs based on the information about parents.

| "...The discordant findings refer to actual heterozygous dogs that had been typed as homozygous for the variant allele. To that aim, the genomic context of the causative variant was investigated in two Hovawart dogs. An insertion of 54 nucleotides composed of a poly-T stretch and 15 nucleotides containing the duplication of the exon 2–intron 2 junction was found. The insertion was responsible for the partial mismatch of the reverse primer used for a direct sequencing assay. The mismatch hampered the amplification of the corresponding allele and caused an evident drop-out effect. The insertion is in complete linkage disequilibrium with the c.118G allele. The allele containing the insertion was highly prevalent in Hovawart dogs, accounting for the 26.6% of allele frequency. The insertion was also found in other unrelated breeds such as Rough Collies and Standard Poodles. (Turba et al 2016) |

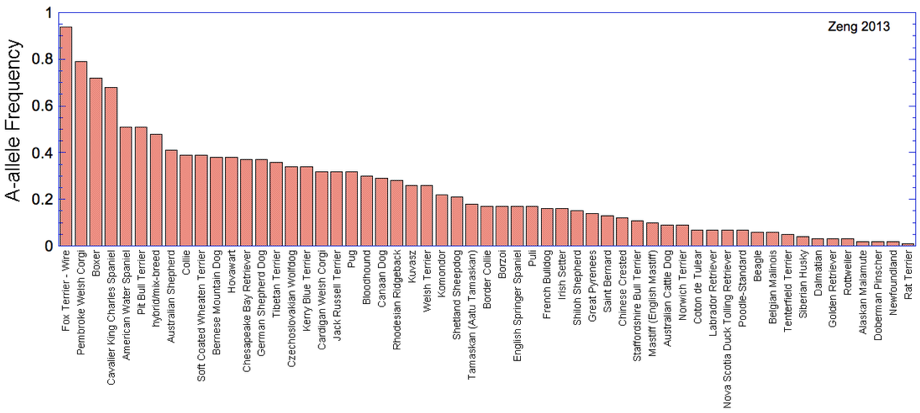

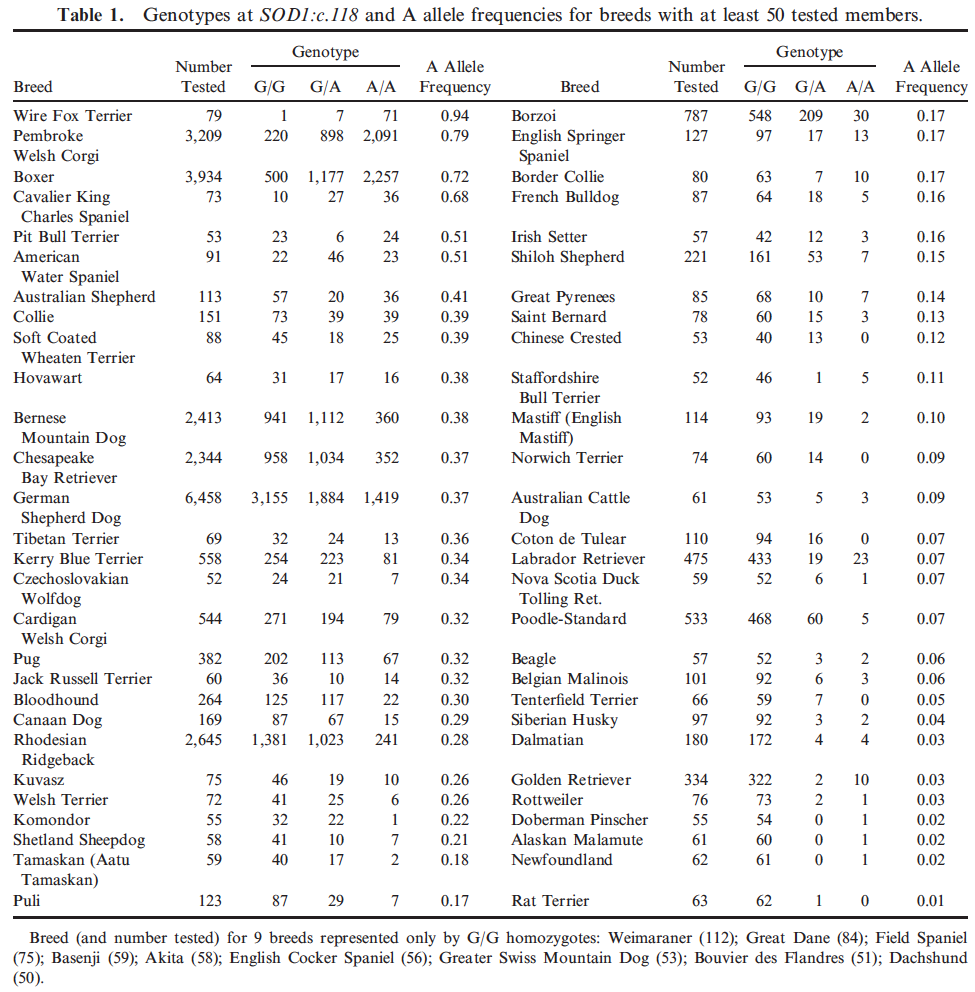

If all that wasn't bad enough, a study of nearly 34,000 dogs has found the original SOD1 to be widespread among dogs (124 of 222 breeds examined), and at a very high frequency in some dog breeds. (For most of the breeds in which the mutation was not found, sample size was low and the data cannot be used to rule out the possibility of occurrence in those breeds.) This graph for breeds with more than 50 dogs tested was created using the data in the table below from Zeng et al. (2014). If allele frequency (y-axis) = 0.5, half of all individuals had the mutation (A allele); if frequency = 1, all animals had the allele.

You can download the table containing all of the data, not just > 50 individuals, here (from Zeng et al. 2014):

Supplementary Table 2 (complete breed incidence data)

With multiple known forms of the SOD1 mutation, widespread distribution of the mutations among many dog breeds, and evidence of a complex interaction with at least one modifier gene, it is clear that the genetics of DM are complex. This is not a disorder that breeders will be able to control with a simple mutation test, and it is very misleading to think of DM as "caused by a mutation". The best strategies for breeders to use for genetic management of DM have not been identified and nobody seems to be addressing this issue, so breeders are making their own decisions and crossing fingers.

The situation is made even more complex because the function of SOD1 is not limited to effects on the nerves for voluntary muscles. In fact, the superoxide dismutase gene produces an enzyme that is a key part of your body's own anti-oxidant defense mechanism. Superoxide dismutase is a "free radical scavenger". Free radicals are highly reactive (oxidative) molecules that are produced by normal metabolic processes but can damage DNA, cells, proteins, and lipids, causing disease. The damaging effects of free radicals are mitigated by the body's antioxidant systems, including superoxide dismutase, and maintaining a balance between the production of free radicals and their inactivation by antioxidants is critical. A mutation in SOD1 doesn't "cause" DM in dogs; it wreaks havoc with the body's essential defense mechanism against free radicals anywhere in the body, including the nerves to the voluntary muscles.

While many breeders hope for DNA tests that will accurately predict risk of DM in dogs, the reality is that not only is this unlikely to happen, but DM is probably not the only problem this mutation is causing in dogs. There is surely a longer list of negative consequences from the SOD1 mutation in dogs that we have yet to connect with this gene. I predict that this will only become more complicated.

___________________________________________________________________________________

REFERENCES

Awano, T., G.S. Johnson, C.M. Wade, et al. 2009. Genome-wide association analysis reveals a SOD1 mutation in canine degenerative myelopathy that resembles amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. PNAS 106: 2794-2799.

Ivansson, E.L., K. Megquier, S.V. Kozyrev, et al. 2016. Variants within the SP110 nuclear body protein modify risk of canine degenerative myelopathy. PNAS 113: E3091-E3100.

Zeng, R. J.R. Coates, G.C. Johnson, and others. 2014. Breed distribution of SOD1 alleles previously associated with canine degenerative myelopathy. J. Veterinary Internal Med. 28: 515-521.

ICB's online courses

***************************************

Visit our Facebook Groups

ICB Institute of Canine Biology

...the latest canine news and research

ICB Breeding for the Future

...the science of animal breeding