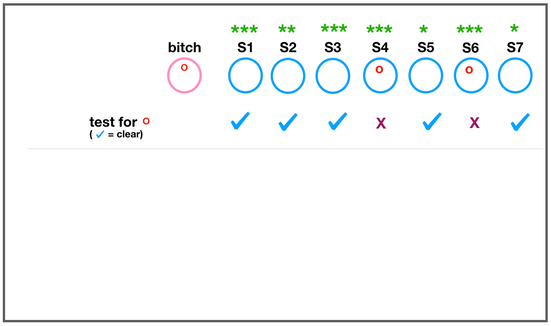

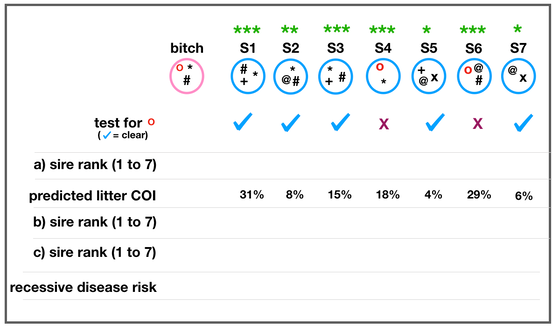

The first thing we need to do is run the appropriate DNA tests for the recessive mutations known to be in the breed. In this case there is one, for the "red circle" trait. Our bitch is carrier, as are two of the sires. I have identified the carriers with a red X on the chart, and the dogs that were clear have blue check marks.

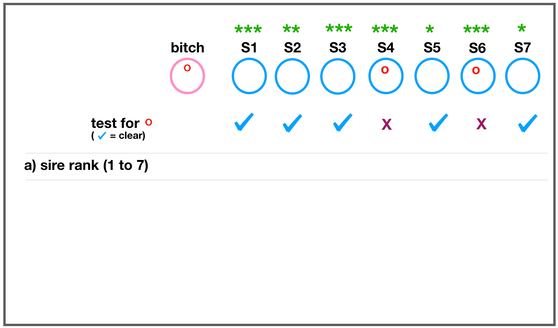

Now we have our health-tested dogs from which we are going to select the perfect sire for our bitch. Using your rankings for overall quality, together with your information from health testing, rank the sires with 1 being your first choice and 7 your last choice.

On your piece of paper, make columns for S1 through S7, and in the first row below that write your ranks for each of the potential sires.

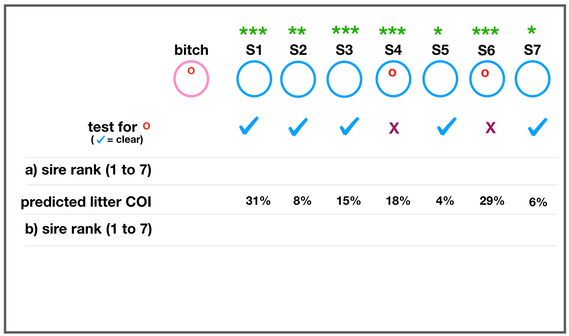

Let's say you went to a little more trouble before making your breeding decision and you were able to get the predicted average inbreeding coefficient of the litters that would be produced from our bitch and each of the seven sires. (You can get this information from the kinship coefficient, which is an index of the relatedness of a pair of dogs and can be determined either from pedigree or DNA information. The kinship coefficient of a pair of dogs is equal to the inbreeding coefficient of their potential offspring.)

Let's add the predicted litter COI to our table. With this information to consider as well, again rank the sires from 1 to 7 and add these data to the next row of your table. (Did this alter your first set of ranks?)

This is usually as much information as a breeder has about the dogs they want to breed.

You did the testing for the "red circle" mutation in our potential parents and discovered that two of the sires were carriers. For both of them, there would be a 25% risk of producing puppies that are homozygous for the red circle mutation. You probably chose to eliminate those two sires from breeding consideration, which reduced the risk of producing affected pups in this litter from 25% to 0%.

You breed using your top-ranked sire and your bitch produces a beautiful litter of puppies. You advertise your pups as being from health-tested parents, keep a lovely pup for your breeding program, and send the rest off to pet homes. Sometime later one of the pet owners contacts you with the report that their puppy has a serious inherited blood disorder, and they ask how this could be if you claimed your pups were from health tested parents?

Indeed. How can this be???

We only know what we can know. We can know if a dog possesses a mutation if we have a test for it. We did our tests so we knew about the status of the red circle mutation in all of the potential parents.

But most dogs have many recessive mutations lurking in their genome for which there is no DNA test, and we have no way to know they are there if they are not expressed. Clearly, there was a mutation in your parents that you didn't know about. You feel horrible, offer to replace the puppy, and bury yourself in pedigrees trying to figure out how you could have produced a puppy with a genetic disease after being so careful.

If there is no DNA test for a recessive mutation, a disease can suddenly appear out of the blue that you have never seen in your lines if you happen to pair two carriers. This is why, if somebody claims that they only breed within their own kennel because they "know what's in their lines", you know that either they don't understand genetics, or they are being dishonest. It is not possible to know what recessive mutations are in your lines if you have no way to detect them.

So this leaves you in a pickle. All dogs have recessive mutations, and there are always going to be some that you don't know about. How do you avoid them? This is like tip-toeing across a mine field in which there are 3 mines that you can't see but are flagged, but you know that there are 28 more hiding out there somewhere. One wrong step and you will meet your maker. If these are mutations hiding in your dogs, this is a pretty hectic way to breed.

What if there were two mine-fields, but you can choose which one to cross. The first minefield has 3 mines you know about and can avoid and 28 that are hidden. The second mine field also has 3 that are flagged, but only 6 more that are hidden. If you're not ready to start your after-life, you would logically decide to cross the second mine field, where the risk of getting blown up is only 25% of the risk in the other one.

How does this apply to dog breeding? Let's pull back the curtain and reveal the unseen mutations in the dogs in our breeding program.

Now we can see the problem. Our bitch has not one but three mutations that are also found in our "health tested" sires. Have a look at your last set of sire rankings. Now that you can see these other mutations, are you still happy with those ranks? If you would like to change your rankings, add another row to your table with these new assessments.

Great, you say. But in the real world, if we don't have tests for those unknown mutations, there is no way for us to avoid them, right?

Actually, there is. You just need one piece of information that in fact you already have - the predicted inbreeding coefficient of the litter.

Remember that inbreeding is defined as the probability of inheriting two copies of the same allele from an ancestor. By definition, then, inbreeding is homozygosity. If the inbreeding coefficient of a dog is 25%, then the probability of inheriting two copies of the same allele from an ancestor is 25%. If that allele happens to be a recessive mutation, then the risk of producing a genetic disorder caused by that recessive mutation is also 25%. Likewise, if the inbreeding coefficient is 10%, then the risk of a genetic disorder produced by a recessive mutation is also 10%.

Think about this. You did mutation testing to eliminate the 25% risk of producing a recessive genetic disorder from two carrier parents. But we just explained that the inbreeding coefficient tells us the risk of producing a genetic disorder from ANY recessive mutation, the ones we know about as well as the ones we don't.

So, we can be clever about this. We can control the risk of genetic disease from all recessive mutations by controlling the inbreeding coefficient of the litter. If we test for red circle and eliminated the carrier sires, it would be dumb to then breed to sire #1. We have paid to eliminate the 25% risk from the known mutation then done a breeding with a 31% risk of producing a disorder from some other mutation we don't know about.

Let's read that again.

We tested, eliminated the carrier sires so there is no chance of producing affected puppies from the known mutation, then we bred to a "clear" dog with a 31% risk of producing puppies with a disorder from some other mutation we don't know about.

You might be breeding "health tested" dogs, but you are still producing puppies with a significant risk of genetic diseases from recessive mutations.

Go back to what we know about the inbreeding coefficient. If our litter has a predicted COI of 10%, then the risk of ANY mutation causing a problem is only 10%, including the one we paid to test for. This is because parents with a kinship coefficient of 10% are less similar genetically than parents with a kinship coefficient of 25%. If the parents have fewer genes in common, there is a lower chance of a puppy getting two of the same mutation from both.

So it's simple. Reduce the risk of genetic disorders in your puppies by reducing the predicted inbreeding coefficient of the litter.

If you've never thought about this before, this should be your light-bulb moment. All this "health testing" is a waste of time and money if we choose parents that produce a litter with an inbreeding level of 38%.

This is the WRONG WAY to use DNA testing. The breeder believes they are doing everything they can to produce puppies that will live long, healthy lives. But in fact they mark the known land mines with flags then assume the coast is clear without considering the risk produced by the many unseen explosives.

To produce healthy dogs, we need to get the risk of problems caused by ALL recessive mutations as low as possible, the ones we know about as well as the ones we don't. You can estimate this risk from the kinship coefficients of the potential parents. These numbers can be computed from a pedigree database, or (even better) they can be determined from the genotype data produced by DNA testing.

Don't waste your money on DNA tests then breed in a way that has a high risk of producing disease. Use those tests to eliminate all risk from mutations we can test for, then use kinship coefficients to make sure we have reduced as much as possible the risk from the unknown mutations hiding out in the genome of every dog.

Learn how in ICB's online course

Managing Genetics for the Future

The next class starts the week of 7 January 2019

We hope to see you there!

ICB's online courses

***************************************

Visit our Facebook Groups

ICB Institute of Canine Biology

...the latest canine news and research

ICB Breeding for the Future

...the science of animal breeding