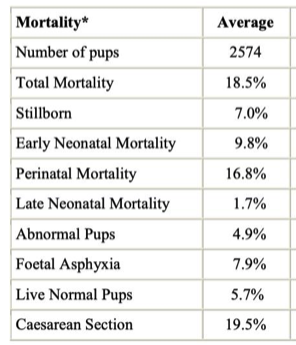

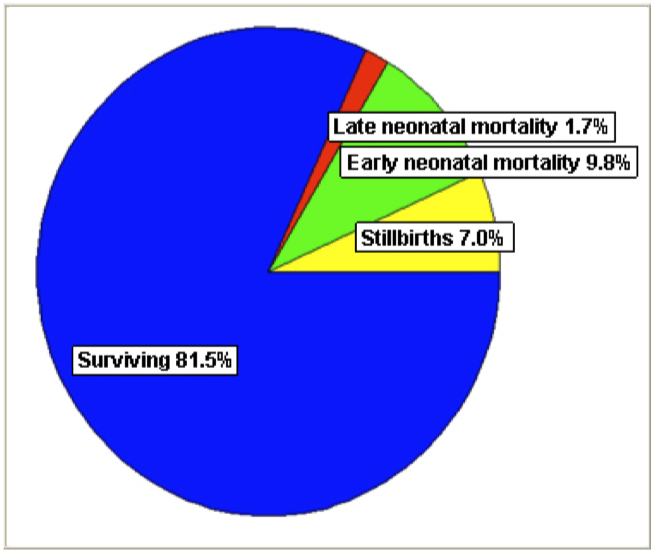

Rates of Mortality in Puppies

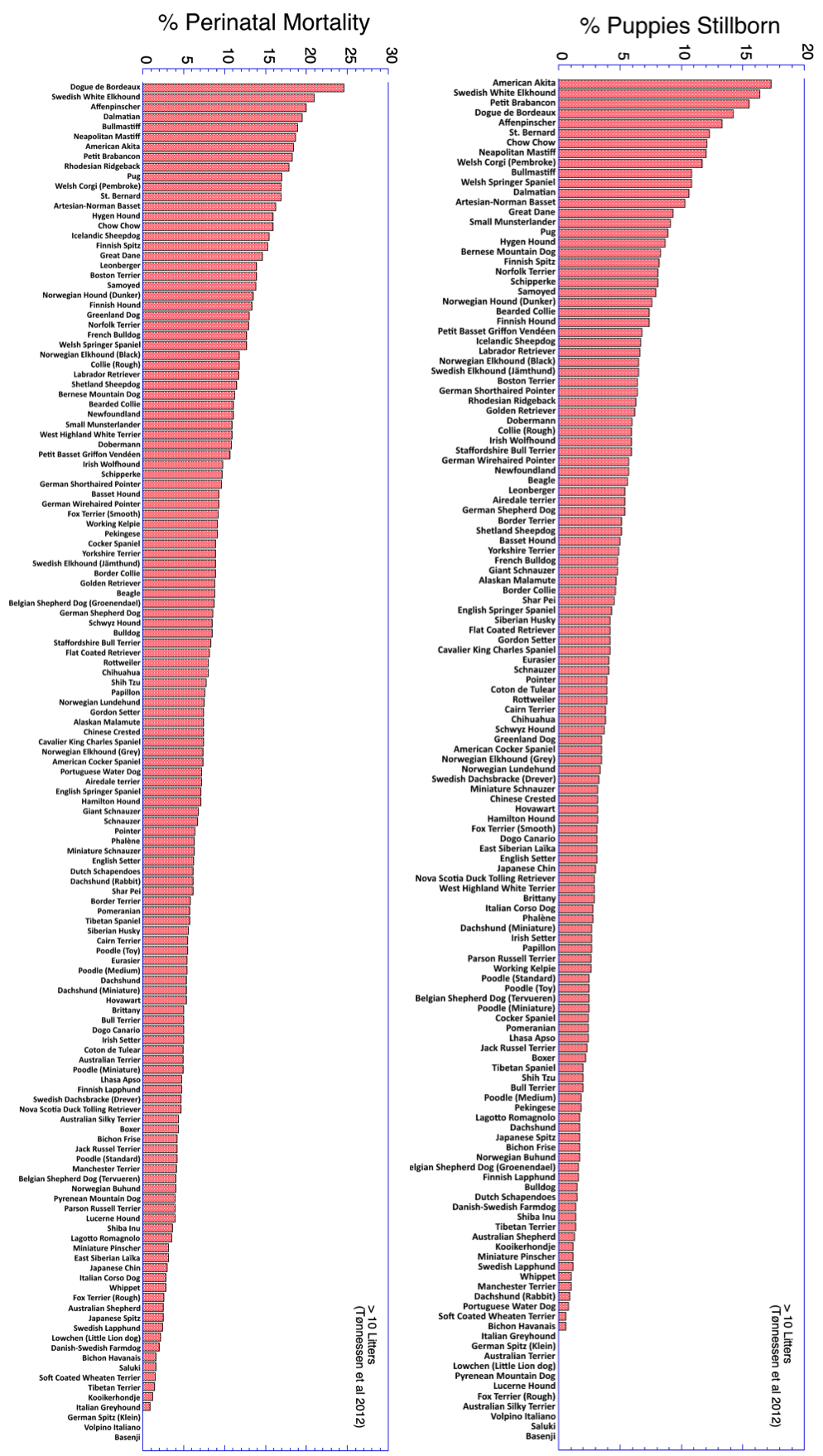

What is evident in these data is the wide range of values across breeds. There are a few breeds in which stillborn or perinatal mortality is very low or did not occur in this sample (e.g., Basenji, German Spitz). But for most breeds, it is clear that puppy mortality is unacceptably high, even greater than 10% in many breeds.

The relative rates of mortality of puppies might seem low (i.e., as a percentage of puppies produced). But the toll in number of puppies lost at birth or shortly thereafter is substantial. The mortality in Tonnessen's study represents deaths of 4,684 puppies over just the period from 2006 to 2007 in Sweden. That's a lot of puppies to lose, year after year after year in one country, but you have to appreciate that the toll worldwide would be in the many thousands.

With the cause of uterine inertia remaining undetermined, there are no recommended procedures for breeders to prevent the high rates of neonatal mortality. Without a cause for uterine inertia, it cannot be prevented and the huge number of deaths of puppies that are perfectly formed but do not survive their first week in this world will continue to accrue.

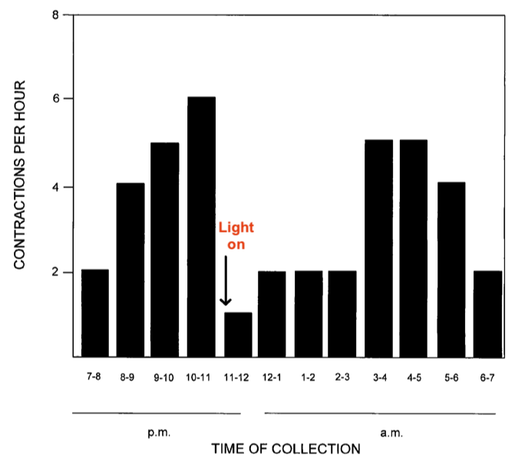

When the whelping room was kept dark, bitches were calmer and more relaxed, and puppies were expelled easily and without straining. Visible abdominal contractions were infrequent. The intervals between puppies were generally short, ranging from 10-30 minutes. When darkness was maintained through whelping of the entire litter, there were no stillborn puppies or pups born in distress. The puppies were vigorous as soon as they were released from the membranes and were able to find and attach to teats without assistance. Between puppies, the bitch cared for the puppies but was relaxed and without signs of stress.

If the bitch was exposed to any light during whelping, as for example by turning on a light or even a cell phone, the appearance of the bitch changed. She appeared less relaxed and abdominal contractions began. This usually lasted for about two hours after the light event and the whelping room was again completely dark. All of the stillborn puppies we observed were born after periods of exposure of the bitch to light with one exception, in which the last puppy in a litter of 15 was stillborn.

The Case for Whelping in the Dark

It makes sense that the physiology of the dog is designed for whelping in the dark.

Wolves and free-living dogs whelp their puppies in underground dens, and the puppies remain in the den for several weeks. Our household pets seek out dark places as whelping nears, disappearing under the bed, in a closet, or behind a piece of furniture. We assume they are looking for a place that is protected, quiet, and cozy, and this might be true. But the key attraction for the dog might be darkness.

Nevertheless, bitches whelping in the house are typically provided a box in a location convenient for monitoring, such as a bedroom, family room area, or even by a window. Because breeders generally supervise and assist with whelping, lighting is at least sufficient for the breeder to see even if it is dim.

But we should be able to dramatically reduce mortality of newborn puppies.

We need to give the bitch access to the conditions that her instincts tell her are best suited for whelping and raising her puppies, instead of what suits our convenience. The physiology of dogs and many other mammals is designed to give birth in the dark. We need to give her darkness.

This is routinely done by keepers of zoo animals, who carefully consider the biology and natural history of an animal in its natural environment in designing its habitat in captivity. Staff supervise by video and intervene if necessary, but, more often than not, birth proceeds without complication or intervention.

Dogs are quite good at reproducing themselves if left to their own devices. We should have fewer complications and much greater success with a simple strategy: just give her what she needs and get out of her way.

Breeders are asking me questions about dark whelping:

- How dark does it have to be?

- Does it need to be dark only during labor, or before (or after) as well?

- Is turning a light on very quickly okay?

- What about a really dim light?

- Is a red heat lamp ok to use?

Unfortunately, the universal answer to these questions is "I don't know".

The dark whelpings I have done have been in absolute darkness (i.e., can't see your hand in front of your face), because this is a light level that can be replicated by every breeder (as opposed to various unknown levels of dimness). Under these conditions, with total darkness and no unplanned "light events", our puppy mortality has been zero.

Total darkness is difficult to do in the typical household. It takes planning and working out critical bits of the logistics ahead of time (e.g., how to retrieve the puppies for weighing without introducing light to the whelping room). But we have been doing it with success, and the extra trouble over a more convenient whelping box in the living room or bedroom is well worth the prevention of mortality.

I can't provide you with a protocol to set up dark whelping yourself. Every breeder's setup is different, and there will be different issues to resolve for the ideal setup for each litter. I can tell you that the process seems to be extremely sensitive to light, and getting it wrong often results in dead puppies.

However, if you would like to whelp a litter in the dark, you can contact me for assistance. I have experience with enough litters now to have worked out at least some of the problems you are likely to encounter.

The sooner we can figure out how to do this right and provide breeders with a protocol they can follow, the sooner we can reduce the tragic loss of puppies that simply run out of oxygen before they make it out into the real world.

Funding through the usual formal channels will take many months or even a year. But we don't need a fancy lab or equipment to do this. I just need breeders with upcoming litters, and some financial support for time to assist with logistics and guidance, and gather the information needed to prepare a protocol breeders can follow. There is lots of compelling research that will come out of this new information about whelping dogs, but for now my priority is to reduce puppy mortality as quickly as possible.

We can prevent puppy mortality from uterine inertia in your very next litter.

If you are interested in supporting the development of a protocol for dark whelping that breeders can use to reduce puppy mortality, please contact me.

Bergstrom A, et al. 2006. Primary uterine intertia in 27 bitches: aetiology and treatment. J Small Anim Pract 47: 456-460.

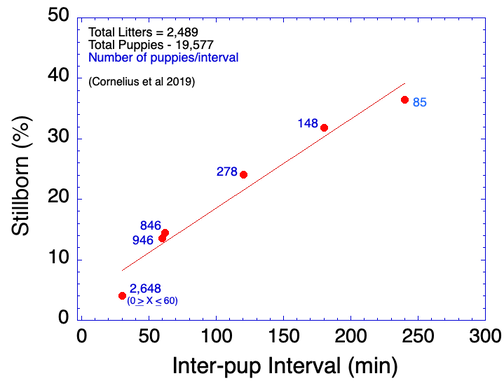

Cornelius AJ et al. 2019. Identifying risk factors for canine dystocia and stillbirths. Theriogenology 128: 201-206.

Gill MA, 2001. Perinatal and late neonatal mortality in the dog. PhD Thesis, University of Sydney.

Olcese J, 2015. Using light to regulate uterine contractions. US Patent No US 8,992,589

Prashantkumar, KA and A Walikar. 2018. Evaluation of treatment protocols for complete primary uterine inertia in female dogs. Pharma Innov J 7:661-664.

Tonnessen R, et al. 2012. Canine perinatal mortality: a cohort study of 224 breeds. Theriogenology 77: 1788-1801.