Animal breeders figured out a long time ago that inbreeding was a marvelous tool. Done carefully, it could mould an animal to suit the needs of the breeder, "fix" the desired traits, and make breeding more predictable. But despite these advantages, there were some significant disadvantages, and one of the most unfortunate was an increase in the number of genetic disorders.

Breeders know that they can use inbreeding to concentrate the genes for the traits they prefer and to increase the predictability of a breeding by reducing variation in the offspring. But breeders have no way to increase the good genes but not the bad ones through inbreeding. (There are ways this can be done, but not using inbreeding.)

But what about dogs that don't have any bad genes? You will hear people say that their lines are "healthy", or that a particular problem is "not in my lines". Can this be true?

| The skeletons in the closet You will know there is a deleterious gene in your lines when it is expressed - that is, whatever bad thing it does becomes evident. If the gene is dominant, an animal that gets a single copy will be "affected" and whatever the normal gene is supposed to do will be broken. But recessive mutations are a different story. If a dog has only a single copy of the gene, it is not expressed. You have no way to know that a recessive gene is there, because it lurks silently while the normal copy of the gene carries out the job it's supposed to do. If the dog has a disorder caused by a recessive gene, you know that dog has two copies. But if the dog doesn't have the disorder, you don't have any way to know if it has only one copy or none unless it produces an affected puppy, in which case both parents must be carrying the gene. |

Recessive alleles are very similar. A dog with one copy is fine, but it will pass a copy to half of its offspring - who will also be fine if they have only one copy. And they will make more new copies of the mutation that get passed to half of the next generation, and the dispersal continues. If it's a huge population of animals, and each of these carriers only has a few offspring, then in a randomly breeding population the chances that carriers might run into each other will be low. But if related dogs are being bred to each other, then they will share some genes, and the more closely related they are the greater the overlap. The most efficient way to produce puppies that will be homozygous for a recessive allele is by breeding closely related dogs. In a population of registered, purebred dogs, ALL the dogs are related if you go back far enough, and the more recent ancestry they share, the more genes - good and bad - they will have in common.

So genetic disorders are a predictable - even guaranteed - consequence of inbreeding in dogs, and in fact in any animal with two sexes. There is always a risk, and you can know that level of risk by calculating the inbreeding coefficient.

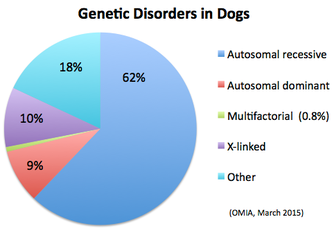

Okay, you say, I get it. But it's not like dogs have zillions of recessive mutations to worry about. In fact, they do - maybe not zillions, but certainly hundreds. In fact, there are FAR more recessive mutations lying in wait than dominant mutations. The OMIA website lists the disorders in dogs and also reports mode of inheritance if it is known. (Note that you don't need to know what the actual defect is to know mode of inheritance, because you can determine this from the pattern of inheritance among a group of related animals in a pedigree.)

Why are there so many more disorders caused by recessive mutations than dominant or x-linked ones? Three reasons:

1) recessive mutations can accumulate in an animal's genes because they can be inherited without detriment;

2) recessive mutations are not selected against unless they are expressed; and

3) inbreeding increases homozygosity, which increases the expression of recessive mutations.

Breeders can't do anything about reason #1, and they can't do much about #2. But reason #3 is the reason why the other two reasons matter -

- Inbreeding increases the expression of recessive mutations because it increases homozygosity.

Expressed another way -

- A high incidence of genetic disorders is a predictable consequence of inbreeding.

In several places on the ICB website there is information about genetic disorders that occur in different breeds of dogs. But the relevant question for our discussion here is how many of these disorders are caused by genes that are recessive?

Here's the (current) list of about 160 disorders caused by recessive genes from OMIA:

- Achromatopsia (cone degeneration, hemeralopia), AMAL

- Achromatopsia (cone degeneration, hemeralopia), GSPT

- Acrodermatitis enteropathica

- Alopecia, colour mutant

- Amelogenesis imperfecta

- Ataxia, cerebellar

- Ataxia, cerebellar, in Old English Sheepdogs and Gordon Setters

- Ataxia, cerebellar, Malinois

- Ataxia, cerebellar, progressive early-onset

- Ataxia, spinocerebellar

- Black hair follicle dysplasia

- Bleeding disorder due to P2RY12 defect

- Brachydactyly

- C3 deficiency

- Cardiomyopathy, dilated

- Cataract, early onset

- Cerebellar abiotrophy

- Cerebellar cortical atrophy

- Cerebellar hypoplasia

- Cerebellar hypoplasia, VLDLR-associated

- Chondrodysplasia, disproportionate short-limbed

- Chondrodysplasia, Labrador

- Ciliary dyskinesia, primary

- Cleft lip and palate

- Cleft palate 1

- Coat colour, albinism, oculocutaneous type IV

- Coat colour, saddle tan vs black-and-tan

- Collie eye anomaly

- Coloboma

- Cone-rod dystrophy 1

- Cone-rod dystrophy 2

- Cone-rod dystrophy 3

- Cone-rod dystrophy 4

- Cone-rod dystrophy, Standard Wire-haired Dachshund

- Congenital keratoconjunctivitis sicca and ichthyosiform dermatosis

- Craniomandibular osteopathy

- Cricopharyngeal dysfunction

- Cystinuria, type I - A

- Deficiency of cytosolic arylamine N-acetylation

- Degenerative myelopathy

- Dwarfism, hypochondroplastic

- Dwarfism, pituitary

- Early retinal degeneration

- Ectodermal dysplasia/skin fragility syndrome

- Encephalomyelopathy and polyneuropathy

- Epidermolysis bullosa, dystrophic

- Epidermolysis bullosa, junctionalis, LAMA3

- Epilepsy

- Epilepsy, benign familial juvenile

- Episodic falling

- Exercise-induced collapse

- Exfoliative cutaneous lupus erythematosus

- Factor VII deficiency

- Fucosidosis, alpha

- Gangliosidosis, GM1

- Gangliosidosis, GM2, generic

- Gangliosidosis, GM2, GM2A deficiency

- Gangliosidosis, GM2, type I (B variant)

- Gangliosidosis, GM2, type II (Sandoff or variant 0)

- Generalized PRA

- Glaucoma, primary open angle

- Glomerulonephropathy

- Glossopharyngeal defect

- Gluten-sensitive enteropathy

- Glycogen storage disease Ia

- Glycogen storage disease IIIa

- Glycogen storage disease VII

- Golden Retriever PRA 1

- Goniodysplasia, mesodermal

- Hyperekplexia (Startle disease)

- Hyperkeratosis, epidermolytic

- Hyperkeratosis, palmoplantar

- Hypomyelination of the central nervous system

- Hypothyroidism

- Ichthyosis

- Ichthyosis, Golden Retriever

- Intestinal cobalamin malabsorption due to AMN mutation

- Intestinal cobalamin malabsorption due to CUBN mutation

- Kartagener syndrome

- Krabbe disease

- L-2-hydroxyglutaricacidemia

- Leber congenital amaurosis (congenital stationary night blindness)

- Lens luxation

- Leukocyte adhesion deficiency, type I

- Leukocyte adhesion deficiency, type III

- Leukoencephalomyelopathy

- Malignant hyperthermia

- Mucopolysaccharidosis I

- Mucopolysaccharidosis IIIA

- Mucopolysaccharidosis IIIB

- Mucopolysaccharidosis VI

- Mucopolysaccharidosis VII

- Multidrug resistance 1

- Multifocal retinopathy 1

- Multifocal retinopathy 2

- Multifocal retinopathy 3

- Multiple system degeneration

- Musladin-Lueke syndrome

- Myasthenic syndrome, congenital

- Myasthenic syndrome, congenital, Labrador Retriever

- Myoclonus epilepsy of Lafora

- Myopathy, centronuclear

- Myopathy, Great Dane

- Myotonia

- Narcolepsy

- Nasal parakeratosis

- Neonatal encephalopathy with seizures

- Nephritis, autosomal recessive

- Nephropathy

- Neuroaxonal dystrophy

- Neurological syndrome

- Neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis, 1

- Neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis, 10

- Neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis, 12

- Neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis, 2

- Neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis, 4A

- Neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis, 5

- Neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis, 6

- Neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis, 8

- Neutropenia, cyclic

- Oculoskeletal dysplasia 1

- Oculoskeletal dysplasia 2

- Osteochondrodysplasia

- Osteogenesis imperfecta_Dachshund

- Persistent Mullerian duct syndrome

- Photoreceptor dysplasia

- Platelet receptor for factor X, deficiency of

- Polyneuropathy

- Prekallikrein deficiency

- Primary hyperoxaluria type I (Oxalosis I)

- Progressive retinal atrophy

- Progressive retinal atrophy type 3, Tibetan Spaniel and Tibetan Terrier

- Progressive retinal atrophy, Basenji

- Progressive rod-cone degeneration

- Pyruvate dehydrogenase deficiency

- Pyruvate kinase deficiency of erythrocyte

- Retinal dysplasia and persistent primary vitreous

- Rod dysplasia

- Rod-cone dysplasia 1

- Rod-cone dysplasia 1a

- Rod-cone dysplasia 2

- Rod-cone dysplasia 3

- Rod-cone dysplasia 4

- Severe combined immunodeficiency disease, autosomal

- Severe combined immunodeficiency disease, autosomal, T cell-negative, B cell-negative, NK cell-positive

- Skeletal dysplasia 2 (SD2)

- Spinal dysraphism

- Spondylocostal dysostosis, autosomal recessive

- Subaortic stenosis

- Thrombocytopaenia

- Thrombopathia

- Trapped Neutrophil Syndrome

- Tricuspid valve dysplasia

- Urolithiasis

- Vitamin D-deficiency rickets, type II

- Wilson disease

- XX testicular DSD (Disorder of Sexual Development)

That's a lot of genetic disorders to dodge. [Note that OMIA lists not only disorders but traits, which can be benign (coat color) or even breed features (brachycephaly). I tried to weed all of these out, but please don't throw me and my list under the bus if I missed one.]

Many of these disorders might not occur in your breed. But if one of them has EVER occurred in your breed, then the mutation is in your breed too. Unfortunately, this is a depressingly long list and it grows longer every month, so we know (and can expect) that there are many more that we don't know about yet.

If you're a breeder, you might be thinking about now that that breeding is a genetic crap shoot and that producing healthy dogs is a hopeless mission. But it's not.

Your dogs will never be afflicted with any of these disorders as long as none inherits two copies of the responsible gene. Controlling these genetic disorders is conceptually simple:

The coefficient of inbreeding is equal to the risk of inheriting two copies of the same mutation from an ancestor on both sides of the pedigree.

If the COI is 10%, then the risk of producing one of these disorders if the gene is in your breed is 10%. If the COI is 25%, then the risk is 25%. It's simple. You can even choose the level of risk you're willing to take.

You CAN manage the risk of genetic disorders in dogs. All you need is a pedigree database and some software that calculates the coefficient of inbreeding. The only reason dogs are afflicted with disorders caused by recessive mutations is because people are taking that risk and losing the bet.

*** "Population Genetics for Dog Breeders" starts 30 March ***

Visit our Facebook Groups

ICB Institute of Canine Biology

...the latest canine news and research

ICB Breeding for the Future

...the science of animal breeding